On the Soul

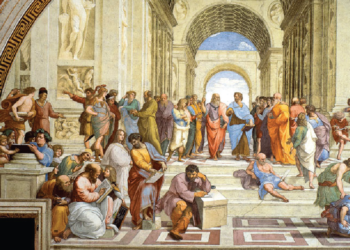

1) Plato on the Soul:

The idea that the soul is the source of both life and the mind was first put out by Plato in the chronicles of philosophy. In Plato’s dialogues, the soul appears in a variety of different roles. Plato had the opinion that the soul is what gives the body life, which was most clearly expressed in the Laws and Phaedrus: to be alive is to be able to move yourself; the soul is a self-mover. He also believes that moral qualities are carried by the soul (i.e., when I am virtuous, it is my soul that is virtuous as opposed to, say, my body). The mind is a part of the soul because it is what we think with.

The three components of the platonic soul are distributed throughout the body in three separate places: The head’s logos (λογιστικόv), or logistikon, controls the other components and is connected to reason. The thymos (θυμοειδές), or thumoeides, is connected to spirit and is situated close to the chest area. Desires are connected to the eros (ἐπιθυμητικόν), also known as the epithumetikon, which is found in the stomach.

Plato claimed that the three aspects of the mind also correspond to the three classes of a society in his work The Republic, as well as in Phaedrus’ chariot allegory (viz. the rulers, the military, and the ordinary citizens). The epithymetikon’s purpose is to create and pursue pleasure. The logistikon’s purpose is to subtly control through a love of knowledge. The purpose of the thymoeides is to follow the instructions of the logistikon while fiercely guarding the whole against infiltration from outside and internal chaos.

Justice (dikaiosyne) is defined as the state of the entire in which each part performs its function, whether that be in a city or an individual. Temperance is defined as the state of the whole in which each part does not attempt to interfere with the functions of the others. Injustice (adikia) is the opposite state of the whole, frequently manifesting specifically as the spirited yielding to the appetitive as they jointly either completely disregard or use the rational in their pursuit of pleasure.

The question of whether the soul is one or divided into pieces is one that Socrates and his interlocutors Glaucon and Adeimantus are attempting to address in Book IV, part 5 of the Republic. According to Socrates, it is evident that a single thing can never experience opposite outcomes in connection to a single thing at the same moment. So that we will understand that there were multiple things operating rather than just one if we ever discover these discrepancies in how the mind works. (This is an illustration of Plato’s non-contradiction principle.)

It would appear difficult for someone to simultaneously desire something and be opposed to it at the same time, as when one feels enticed to commit a crime but also opposed to doing so, given that each individual has only one soul. Socrates and Glaucon both concur that it shouldn’t be feasible for the soul to be in one state and its opposite at the same time. This implies that the soul must have at least two aspects. After referring to these as “reason” and “appetite,” Plato goes on to name a third element, “spirit,” which in a sound mind should be in line with reason.

The reasoning aspect of the soul that loves the truth and strives to discover it is called the logical, or logistikon (from the Greek word logos). The Athenian temperament is the first thing Plato associates with the soul ruled by this component. The logistikon would be the smallest component of the soul, according to Plato (as the rulers would be the Republic’s smallest population), but a soul can only be deemed to be just if all three parts agree that the logistikon should reign. According to Plato, the portion of the soul that causes us to become angry or irritable is called the spirited or thymoeides (from the Greek word thymos). He also refers to this component as “high spirit” and initially associates the Thracians, Scythians and the people of “northern regions” with the soul this part dominates.

The ideas of Socrates and Pythagoras were united in Plato’s thesis of the reincarnation of the soul, fusing the divine rights of humanity with the route of reincarnations between various animal species. He thought that the rewards for virtue bestowed on humans and the punishments meted out to the guilty took place right here on Earth. In accordance with Plato’s view that women occupied a lower level of the natural scale, a sinful soul would be reincarnated after death first in a woman and then in an animal species, descending from quadrupeds down to snakes and fish. This idea claims that women and the lower animals were merely made in order to house degraded souls.

Most often, Plato asserts that the afterlife has a unique reward and punishment period in between reincarnations. The reward and punishment phase only vanishes in the Timaeus and Laws; in these two books, reincarnation itself is claimed to be the punishment. Recent academics have claimed that the reincarnation hypothesis is meant to be taken literally. It appears elsewhere as the conclusion of other philosophical commitments that Plato argues for, such as the idea that virtue is always rewarded and vice punished and the idea that the only way to punish a soul is to embody it. For example, it appears in the Timaeus as a scientific theory to explain the generation of non-human animals.

2) Aristotle on the Soul:

Aristotle’s theory, as it is primarily described in the De Anima is very close to offering a thorough, fully developed account of the soul in all of its aspects and functions, an account that articulates the ways in which all of the vital functions of all animate organisms are related to the soul. By doing so, the theory very nearly provides a comprehensive response to a query arising from the common Greek understanding of soul, specifically how precisely the soul, which is acknowledged to be in some way responsible for a variety of things living creatures (especially humans) do and experience, also is the defining characteristic of the animate.

According to Aristotle’s conception, a soul is a specific type of nature, a concept that explains how living bodies—plants, nonhuman animals, and people—change and rest. According to Aristotle, the relationship between the soul and the body is a specific type of in-formed matter. This relationship is also an example of the more general relationship between form and matter.

We can characterise the theory as providing a unified explanatory framework within which all vital functions, from metabolism to reasoning, are treated as functions carried out by natural organisms of suitable structure and complexity. To do this, we need only limit ourselves to the sublunary world. In this framework, the system of active abilities that an animate organism possesses to carry out the essential tasks that organisms of its kind naturally perform constitutes its soul. As a result, when an organism engages in the relevant activities (such as nutrition, movement, or thought), it does so thanks to the system of abilities that constitutes its soul.

It is obvious that the soul is neither a body or a corporeal object in accordance with Aristotle’s view because the soul is a system of skills that are held and displayed by animate bodies with appropriate structures. Aristotle concurs with the Phaedo’s assertion that souls and bodies are very distinct from one another. Additionally, Aristotle seems to believe that all of the capacities that make up the souls of plants, animals, and people are such that using them necessitates the use of corporeal organs and parts. This is unquestionably the case for capacities like spatially appropriate mobility (such as walking or flying) and sense perception, which depends on sense organs.

But since Aristotle rejects the idea that there is an organ of thought, he also rejects the idea that using one’s mind requires using an organ or body part that was specifically designed for that purpose. However, he does appear to hold the belief that the activity of the human intellect always involves some activity of the perceptual apparatus, and therefore requires the presence, and proper arrangement, of suitable bodily parts and organs. He seems to believe that sensory impressions [phantasmata] are somehow involved in every occurrent act of thought. If this is the case, Aristotle appears committed to the idea that, in contrast to the Platonic stance, even human souls are not capable of being and (maybe more significantly) activity apart from the body.

It is important to note that Aristotle’s theory does not distinguish between the vital functions that are mental and the soul in any way that is distinct from or goes beyond how the vital functions are generally related to one another. It is undoubtedly not part of Aristotle’s view that the soul specifically performs mental activities on its own and is directly accountable for them, whereas it is less directly responsible for the execution of other critical duties by the living creature, such as growth. According to this aspect of his theory, Aristotle is confident that once one has a proper understanding of how to explain natural phenomena in general, there is no reason to believe that mental functions such as perception, desire, and at least some types of thinking cannot be explained by simply making use of the principles in terms of which natural phenomena in general are properly understood and explained.

One can argue that Aristotle’s philosophy obfuscates a critical distinction by treating mental functions and other essential activities precisely the same. But it turns out that this concern was unfounded. Only in that it considers both types of activities to be carried out by natural organisms with the appropriate level of complexity and structure does the theory regard mental and other important functions similarly. If issues of any type call for a separation between mental and other functions, viewing mental and other important functions in this way is fully compatible with establishing that differentiation. For example, Aristotle is completely capable of excluding non-mental vital functions from the scope of practical philosophy.

3) Alexander of Aphrodisias:

Alexander explains a particularly challenging aspect of Aristotle’s psychology in chapters 4 and 5 of Book III of On the Soul. Alexander claims that Aristotle teaches the existence of two types of intelligence: one that is identical to the Supreme Deity and is known as active intelligence (it is this intelligence that continuously and eternally perceives itself by perceiving the “higher” intelligibles), which is different for every individual and is a part of everyone’s soul.

This intelligence-Deity is distinct because it “enters” man from without (i.e., it is not attached in any way to his body) and because it activates human intelligence, allowing it to perceive both lower-order and higher-order intelligibles. Alexander refers to human intelligence as being “in action” or “acquired as habit” or “acquired as disponible skill,” or we could say “activated” (or “transformed,” and Alexander almost says “divinized”) in various elements of its activity. The denial of any form of personal immortality is the theory’s most obvious outcome.

Man’s intelligence, as it was altered by the active intelligence, endures by being reabsorbed into that particular, impersonal, divine intelligence; but, man’s soul perishes with his body. It is interesting that Pseudo-Alexander refers to the “transformation” experience, which occurs when human intelligence is able to perceive the “higher” intelligibles, as an ethereal (indescribable) event. One of the major debates of the Middle Ages and the early Modern Era was whether or not Alexander’s reading of Aristotle was valid, and even more, whether or not the theory (the denial of personal immortality) was correct.

4) Plotinus on the Soul:

Plotinus refers to “the One” (or, alternatively, “the Good”), “Intellect,” and “Soul” as the three fundamental concepts of his metaphysics. Life’s guiding principle is not the soul because intelligence is life’s highest form of activity. Plotinus equates desire with life. The highest type of desire, however, is found in the life of intellect, the highest life, and this desire is forever gratified by contemplating the One through the vast variety of Forms that are inherent to it. The foundation of desire for things outside of the desire agent is the soul. Everything with a soul, including people and even the tiniest plant, acts to gratify desire.

It must look for items that are outside of itself, like food, to satisfy this want. Even the urge to sleep, for instance, is a desire for a different state from the one the living thing is currently in. Cognitive needs, such as the need to know, are aspirations for that which the agent does not presently possess. Plato noted that the desire for procreation is the longing for immortality. Unchangeable Intellect was unable to explain the deficit that is inherent in the act of seeking, but Soul is able to do so.

Similar to how intellect is tied to the One, soul is related to intellect. Intellect is archetypal of what Soul is, just as the One is basically what Intellect is. The paradigm for all embodied cognitive states of any soul as well as any of its emotional states is the activity of Intellect, or its cognitive identification with all Forms. First, by virtue of having a representational state, a mode of cognition, such as belief, represents Intellect’s eternal state. Because the embodied believer is cognitively identical with a concept that itself embodies or depicts Forms, it symbolises the cognitive identity of Intellect with Forms. In the second instance, an affective state—like being tired—represents or conjures up Intellect (in a derived sense) because it has a cognitive element that entails self-awareness. In this case, x’s being-in-the-state serves as the cognition’s intentional object.

The imitation is even more away when the affective state is that of a non-cognitive agent, yet it is still present. According to Plotinus, it is comparable to the difference between the states of being awake and asleep. In other words, it is a state that generates desire and is capable of recognising its presence, a state that symbolises the state of Intellect. The affective states of non-cognitive agents can only be understood as derivations of the affective and cognitive states of souls closer to the ideal of both, namely the state of Intellect. Plotinus will want to insist that potencies are functionally related to actualities, not the other way around, in response to the potential objection that a potency is not an image of actuality.

As intellect is connected to the One, there is another way that soul is connected to intellect. Plotinus makes a distinction between an object’s interior and exterior behaviour. The One’s hyper-intellectual existence is its (indescribable) internal activity. Just intellect is what it does outside the body. The same is true for Intellect, whose internal activity is its study of the Forms, and whose external activity is found in every conceivable portrayal of its activity of being eternally identical with everything that is intelligible (i.e., the Forms). The activity of the soul, which functions as a principle of ‘external’ want and represents the archetypal desire of Intellect, also contains it.

Any sort of cognition that can be understood is an external action of intellect, as is anything that can be comprehended. The vast array of psychical activities that all embodied living creatures engage in are included in the internal activity of the Soul. Nature, or everything in the sensible universe other than soul, including both the bodies of things with soul and objects without soul, is the external activity of soul. The result of this cycle of decreasing activity is matter, which is ultimately due to the One, through the use of Intellect and Soul, but is completely devoid of form and therefore of intelligibility.

5) Augustine on the Soul:

Augustine emphasises the importance of understanding the soul in his quest for knowledge, as evidenced by his declaration that he longs “to know God and the soul” (Sol. 1.2.7). And when Reason, with whom he speaks in the Soliloquia, asks him if there is anything else he would like to know, he responds, “Absolutely nothing.” Later, he prays, “God ever the same, may I know you, and may I know myself,” expressing the same wish. Despite the fact that every living thing has a soul, Augustine is primarily interested in the human or reasoning soul.

He refers to the soul in general using the Latin word anima while designating the rational soul with animus or mens. A human being, as viewed by a human being, is a rational soul employing a mortal and earthy body, according to De moribus ecclesiae catholicae 1.27.52, and he defines the human soul in Platonic fashion as a definite essence participating in reason and equipped to rule the body (De quant. anim. 13.22). He emphasises the human being’s unity more in his later writings. Despite the fact that Augustine defines a human being as a rational soul with a body, he also claims that the soul with a body does not form two persons, but one human being. (In Johannis evangelium tractatus 19.15).

6) Aurelius on the Soul:

The soul of man violates itself, especially when it begins to grow on the universe and resemble an abscess insofar as that is possible. Because having negative feelings about anything that occurs is a departure from nature, each of the remaining parts’ natures are affected. And secondly, whenever a man’s soul rejects him or even acts against him out of malice toward him, as is the case with angry people’s souls. Thirdly, when one is overpowered by effort or pleasure. Fourth, anytime it plays a role and is misleading or deceptive in what it does or says. Fifth, even though it is required for even the smallest things to happen with the end in mind, it directs its own deed or desire at no purpose but wastefully and ineffectively expends energy on anything at all. Following the oldest city and government’s rationale and legislation is how logical animals come to an end. This section occurs at the end of Book 2 of the Meditations, which is the first “philosophical” book of the work.

Book 1 is a list of gratitudes for the virtues that Marcus Aurelius has accumulated throughout the course of his life from various persons at various points. For those who are unfamiliar, Marcus Aurelius, who ruled Rome for approximately twenty years starting in 161 AD, is the author of this treatise. Naturally, despite being Roman, he wrote in Greek while camped out in between different military operations against the barbarians. He is a writer who has frequently been accused of being inconsistent with the Stoic tenets, but his work consistently bears the stamp of that philosophy.

Before this, Marcus had criticised people for focusing more on their own affairs or “things underneath the earth,” the latter phrase possibly demeaning metaphysical speculation or, alternately, a means to group any philosophical reflection that is not moral. One should devote time to their inner divinity, a euphemism for their true selves and possibly indicative of the extremely cerebral outlook that the Stoics advised for people.

The soul violates itself in five different ways. The first approach needs to be understood in light of the famous Stoic imperative: Live in harmony with the environment. As Marcus criticises a disposition that could become a tumour on the universe, he qualifies his criticism by adding, “as far as it is able.” Due to the rigorous determinism of the Stoics, who believe that the cosmos will always work in the best interests of all living things, this requirement is necessary. Marcus may be confining the area of intended deviation to thought rather than action in this way. The subsequent phrase, “For feeling dislike for anything which happens is an apostasy from nature…” supports this view. The mind may rebel, at least in theory; but, no actual action can upset the design of Nature. This infringement contains an insightful metaphor. What could be more out of the ordinary for a body than a tumour? Similarly, what could be more out of the ordinary for the cosmos than someone trying to somehow undermine it?

To “turn away” from another person is the second self-violation of the soul. The wording here must indicate “not help.” Such a person “turns from” their fellow man instead of aiding them by “coming to” them. We must adopt this interpretation in order to make it consistent with the example—a person in a rage—provided. Although an angry person metaphorically “turns from” the target of their wrath in Marcus’ phrase, they actually “turn to” that target, as any recent target of rage will attest. The third piece of advice, to never be deceived by pleasure or toil (pain), is self-explanatory. This is not the same as experiencing pleasure or pain; rather, it refers to the dominant role that those two emotions may play in a person’s day-to-day activities.

Fourthly, the soul sins when it pretends to be a hypocrite by acting or speaking in an untruthful manner. The limited description provided makes it unclear, although it’s probable that the term embraces any form of lying. Lying would mean betraying one’s own integrity as a rational person with a built-in ability to think truthfully. This comprehension of the fourth command flows naturally into the next.

The fifth method a soul can harm itself is by doing without thinking about the outcome. This is the same as existing as a mere organism on your own, breathing and awakening only to do it again. This also includes any and all actions that are conducted without a clear grasp of their intention or final result. If one were to read the Meditations without having any objective of self-improvement or some specific goal in mind, I imagine that doing so may be done in a nasty way. “The end of logical animals is in following the reason and law of the city and government which is oldest,” Marcus concludes his piece of wisdom.

When the subject of right action is brought up, as in most Stoic literature, the notion of conformity with the cosmos is always present. Man must live in conformity with the actual cosmos, a domain deliberately created for among other things, rational creatures, as well as his actual self, that is, as a rational being. The rational being must adapt his behaviours and thinking to this earliest “city and government.”

7) Al-Farabi on the Soul:

Al-Farabi is generally understood to have identified four soul faculties: the appetitive (desire), sensitive (perception/senses), imaginative (interpretation/categorization of sensations), and rational (reason/cognition). All living things, from the lowest plant life to animals and people, fall within Al-Farabi’s hierarchy of the soul. The logical soul is reserved just for humans.

All of the soul’s faculties are present in humans, but the rational soul—the faculty of reason and will—rules supreme and is in charge of exerting control over the other, weaker faculties of the soul (appetitive, sensitive, and imaginative). Even if the major divisions of the soul (for Al-Farabi) seem to be four faculties instead of three, we can still observe the intrinsic similarities between Al-Farabi and Avicenna in this passage. A different interpretation of Al-Farabi’s psychology however, depicts the soul in a manner that is even more like that of Avicennian psychology. For this, we’ll examine Robert Hammond’s interpretation of Al-Farabi.

Hammond claims that Al-Farabi actually divides the soul into three faculties or classes: the Vegetative, the Sensitive, and the Intellective in The Philosophy of Al-Farabi and Its Influence on Medieval Thought. There are certain power sets that may be attributed to each of these divisions. The Nutritive, Augmentative, and Generative Powers are a part of the Vegetative Faculty, whereas Knowledge Power and Action Power are a part of the Sensitive Faculty and Intellective Faculty, respectively.

Let’s examine Hammond’s division now, beginning with the Vegetative Faculty. It possesses a nutritional force that is essential for feeding, obtaining food, and maintaining even the most basic forms of life. It also has a power for growth known as an augmentative power. The third power is generative, which is the ability for self-preservation (reproduction/procreation) that every living thing contains. The Philosophy of Al-Farabi and Its Influence on Medieval Thought, by Hammond, The similarities to the Avicennian Plant Powers, which also encompass nutritive, growth-promoting, and generation, are immediately apparent (Propagating).

The Vegetative Faculty, according to Avicenna, is a component of all living, ensouled things, including humans, animals, and plants. The Vegetative Faculty is vital for living and thriving (and continuing to exist). Hammond then dissects the soul’s sensitive faculty. Al-Farabi separates the Sensitive Faculty into Knowledge and Action, according to Hammond.

Sensitive Knowledge is by nature observant and sensuous. It is the concepts and perceptions we acquire from our senses, both internal (such as imagination, memory, and instinct) and external (such as the five senses). The concepts and images we gather through our senses are converted into valuable information by this Knowledge Power of the Sensitive Faculty. Either locomotive or sensitive is the Action Power.

“Concupiscible and irascible” best describes Sensitive Action. This seems to imply that people who have the sensitive faculty behave according to whether or not something is attractive. Based on the information gathered through the external senses and retained and used by the internal senses, an ensouled entity would be able to determine if something is good or evil.

The actual capacity for (willful) movement in living beings that possess the sensitive faculty of the soul is referred to as the locomotive element of the action power (animals and humans). It is common to find this Sensitive Faculty in both people and animals. Al-Farabi’s Sensitive Faculty and Avicenna’s Animal Powers appear to be related in some way. The powers of Al-Farabi’s Sensitive Faculty and those of the Avicennian Animal Faculty are essentially the same, including perception, imagination, purposeful movement, etc. They both encompass, for the most part, very comparable components of the soul.

We now get at Al-Farabi’s third division of the soul, the Intellective Faculty. Knowledge and action are the two attributes of the Intellective. Al-Farabi believed that there are two types of intellectual knowledge: perceptive (“knowledge of the individual”) and abstractive (“knowledge of the universal”).

Action is the second ability of the intellectual faculty. According to Al-Farabi, this action power is what Hammond refers to as “the will”. What distinguishes people from the other ensouled living things is this action—the will. Humans, as opposed to plants and animals, are capable of making conscious decisions and doing intentional action. For Al-Farabi, morality in humans is enabled through Intellective Action.

In other words, humans have the capacity to use everything they learn through their sensitive (animal) faculty in ways that are either moral or immoral. To accomplish this, we require choice and will. As a result, what sets people apart from the rest of the living world is their intellect (both in knowledge and action).

8) Ibn-e-Sina on the Soul:

One of the most influential thinkers in the mediaeval Hellenistic Islamic tradition, which also includes al-Farabi and Ibn Rushd, is Ibn Sina (Avicenna). He finds a systematic place for the physical universe, spirit, insight, and the different types of logical thought, such as dialectic, rhetoric, and poetry, in his philosophical theory, which is a thorough, in-depth, and rationalistic account of the nature of God and Being.

Ibn Sina’s view of reality and logic is essential to his philosophy. According to his plan, reason may help people advance through several stages of understanding and ultimately point them toward God, the source of all truth. In his theory of knowledge, which is founded on the four faculties of sense perception, retention, imagination, and estimation, he emphasises the value of learning new things. The main function of intellect is imagination since it can compare and create images that give it access to universals. God, the supreme intellect, is once again the ultimate object of knowledge.

Ibn Sina distinguishes between essence and existence in metaphysics; essence solely considers the character of things and should be considered independently of their mental and physical realisation. Except for God, whom Ibn Sina sees as the initial cause and consequently both essence and existence, this distinction is applicable to all things. In addition, he claimed that because the soul is intangible, it cannot be lost. According to him, the soul has the ability to choose between good and evil in this life, which results in either reward or punishment.

Ibn Sina’s purported mysticism has occasionally been brought up, but this seems to be the result of Western philosophers misinterpreting certain passages in his writing. Ibn Sina, one of the most significant thinkers, had a significant impact on both mediaeval Europe and other Islamic philosophers. One of the principal focuses of al-Ghazali’s critique of Islamic influences from the Hellenistic world was his work. His writings, which were translated into Latin, had an impact on other Christian intellectuals, most notably Thomas Aquinas.

9) Ghazali on the Soul:

The phrases “al-qalb”, “al-ruh”, “an-nafs”, and “al-‘aql”, which allude to the soul, were used by Al-Ghazali to describe the topic of the human soul. He went on to say that each of those statements has a spiritual and a physical significance. Al-qalb, the first phrase, literally translates to “al-lahm al-sanubari”, or “a piece of flesh located in the left side of our body”. Al-Ghazali referred to it as the heart of human spirituality, or al-Latifah al-Ruhaniyah (spiritual subtlety), which distinguishes men from other living things.

Al-Latifah al-Ruhaniyah, also known as spiritual subtlety, is something that was formed, which means it is a type of creature but is also immortal and neither quantifiable nor limited by space and time. The other three, Al-ruh, an-nafs, and al-‘aql are seated on the qalb that prepares people to be accountable for their actions in this life.

The three forms of al-qalb that Al-Ghazali described were qolbun salim (the healthy heart), qolbun maridh (the diseased heart), and qolbun mayyit (the dead heart). A heart that has been purified of any passion that questions what God requires or contests what He forbids is said to be qalbun salim. As a result, it is protected from desires that are inconsistent with His good and from worshipping anything other than Him. Next is qolbun maridh, which describes a heart with both illness and life in it. It follows whichever one of the two controls and maintains it at any given time—the former at one point, the latter at another. The worst kind of heart is qolbun mayyit, or a lifeless heart that has no desire to know its Lord or obey its God. It pursues his lower self to satisfy his worldly desires in this life and worships things other than Him.

The second word mentioned by Al-Ghazali is ar-ruh, which refers to the physical component of the heart that causes the entire body to vibrate like an electrical current. It may also be compared to how a room is illuminated by a lantern. In this physical meaning, ar-ruh is viewed in modern medicine using infrared technology as the body’s red heat, which begins at the heart and spreads to the entire body. When a person passes away, this red heat is no longer present.

The second meaning refers to an immaterial substance that springs from the divine mandate, as stated in the Qur’an, that He breathed into (Mary’s body), and as something about which men’s understanding of that spirit is limited. This second meaning of ar-ruh enables a person to be alive and enable all of his organs and soul to function. Al-Ghazali also asserted that ar-ruh is innately knowledgeable and perceptive since it comes from God, who is explicitly declared in the Qur’an as the sole God, as all people have confirmed. In other words, people are aware that He is the universe’s ruler.

An-nafs, the third term, has two distinct meanings according to Al-Ghazali. The first interpretation alludes to the immaterial being, sometimes known as the ego, or lower self, which contains the animal faculties that conflict with the intellectual faculties. This nafs is the origin of a man’s negative sexual urge and fury, which clouds his judgement and tempts him to disobey his Lord. Sufis view this nafs as a man’s negative characteristics and highlight the need to combat it and subdue it, citing a Hadith from the Holy Prophet that claims men’s deadliest enemy is their nafs, which lies between their sides.

The second sense refers to the immaterial aspect of man, his true nature and essence. This is the nafs that can be drawn upwards toward the celestial realm from which it first emerged and was created. To be more specific, Al-ghazali separated this second nafs into three stages: Nafs al-mutma’innah (the Self at Peace), Nafs al-lawwamah (the Blaming Self), and Nafs ammarah bi al-su’ (the self urging evil).

The superior phase of nafs is known as nafs al-mutma’innah, or the self at peace. When a person reaches this stage, he is completely satisfied and at ease. This level of nafs finally aids in resolving one’s internal problems and achieving peace with God; as a result, one’s personality is now adorned with His universal colour and one’s behaviour exhibits the Absolute being and the Ultimate Reality. The state of nafs that arises from the repulsive characteristics of nafs ammarah bi al-su’ is known as nafs al-lawwamah, or the blaming self. When a person is at this stage of nafs, they struggle with their inferior selves, chastise themselves for falling victim to this, and stop themselves from moving forward.

The self-urging evil, or Nafs ammarah bi al-su, is the lowest state of nafs. This nafs is described by Daud Hamzah and Kadir Arifin as the motivation behind cruelty and perverted sex. The fact that this nafs is a part of the syaithan means that it does not subject to God either. It brings out the worst qualities like cruelty, selfishness, worldliness, illusions, immorality, indecency, arrogance, pride, conceit, jealousy, envy, malice, revenge, treason, betrayal, negligence, and disregard for the Almighty.

Al-‘aql, the fourth term covered by Al-Ghazali, has two distinct meanings as well. The understanding of everything in this universe is the first meaning. It might be argued that it is knowledge that resides in the soul or al-qalb. Al-Ghazali emphasises knowledge and its qualities in this sense. Al-‘aql, here, refers to the ‘aql that acquires the knowledge itself (al-mudrak Ii al-‘ulum), and is also referred to as al-‘aql ar-ruhaniyah.

Al-Ghazali conceived of the body as a kingdom, the soul as its king, and the other senses and faculties as making up an army, in order to make the concept of the human soul obvious. Passion is sometimes referred to as the revenue collector, reason as the vizier or prime minister, and rage as the police officer. While resentment is constantly prone to harshness and extreme severity under the pretence of collecting money, desire is constantly prone to theft on its own account. Both the tax collector and the police officer must be kept in the king’s rightful subordination; nevertheless, they must not be slain or surpassed because they both have their own distinct roles to play.

But the destruction of the soul invariably follows when anger and passion rule reason. Al-Ghazali went on to enlighten that a soul who permits its inferior faculties to rule over the superior is as one who should subject an angel to the authority of a hound or to the rule of an unbeliever.

Similar to other Muslim philosophers, Al-Ghazali divided the faculties or powers (quwah) of the soul into three distinct souls, namely the vegetative (al-nabatiyyah), the animal (al-hayawaniyah), and the human/rational soul (al-natiqah). The vegetative soul has the capacity for growth, sustenance, and procreation. Both animals and people have these skills. While man also possesses the animal soul. The intellectual soul of a human being is what distinguishes him from other creatures and makes him a special creation of God.

As a result, according to the term “al hayawan al-natiq”, man is a “rational animal”. By “rationality”, the term refers to “an inner ability that man possesses that formulates meaning (dhu nutq)”. Therefore, aql is a spiritual substance that gives people the ability to discern and discriminate between truth and falsehood. It also gives people the ability to hear the word of truth that the Lord Almighty sends through His messengers.

Al-Ghazali asserts that the soul has two different types of soldiers. The first is the soldier who can be seen; they are made up of the parts of the body that obey the soul. The second kind of soldier consists of thoughts and perceptions and is unseen. He continued by saying that there are three further categories into which the soldiers can be grouped: The first is Irada (the will), which initiates emotions like hunger (shahawa) and rage (ghadab). The second category is qudra (power), which comprises the sinews and muscles and is what actually causes the members to move, and lastly, al-ilm wa’l-idrak, that is, knowledge and perception, which provides information acquired through the five external senses of hearing, sight, smell, taste, and touch, as well as the five internal senses located in the brain which consist of imagination (takhayyul), the census communes (hiss mushtarak) (which coordinates information received through the various faculties), thought (tafakkur), remembrance (tadhakkur), and memory (hifz).

Al-Ghazali described four characteristics of the soul that are present in every soul: predatory (sabu’iya), animal (bahimiya), satanic (shaytaniya), and divine (rabbaniya). The first quality is the capacity for anger, the second is the hunger for food, sex, and other things, the third quality refers to the capacity for evil, and the fourth quality is Divine, which is the highest quality and calls for the most in-depth research and understanding in order to reveal the tricks of the satanic quality and subject the appetite to the irascible faculty.

Al-Ghazali went on to explain that the animal quality produces hypocrisy, slander, greed, and shamelessness, the predatory quality produces wastefulness, boasting, pride, and a desire for oppression, and the satanic quality, after successfully encouraging the soul to obey the first two, produces guile, deceit, fraud, and other vices. However, if the divine element wins and conquers all of these, the virtues will manifest. Man gets attributes like courage, generosity, self control, patience, forgiveness, and dignity when he learns to control and confine his predatory nature. The virtues of chastity, contentment, modesty, and helpfulness come about when the animal faculty is under control.

10) Mulla Sadra on the Soul:

There were two major schools of thought on the human soul prior to Mulla Sadra. One was the Platonic view, which held that the soul existed before the creation of the body and was everlasting and spiritual (Timaeus). The second concept, which belonged to peripatetics, was fully explained by Ibn-Sina. This theory addressed both the corporeal genesis and formation of the body and the immaterial or non-corporeal origin of the soul. Mulla Sadra, however, put out a novel perspective in this area. He demonstrated that, even though the human soul eventually becomes immaterial during the course of its individual growth, it is initially physical and is created from the body.

The human soul is initially solid, according to Mulla Sadra. The soul enters the vegetative stage after leaving the solid stage, where it first appears as an embryo. Later, it enters the animal stage (animal soul), and as it matures truly, it then reaches the human soul stage and transforms into a “rational soul”. It can also acquire human maturity after this stage, given its efforts, practise, and training in reason and religion (which he calls the holy soul and the actual intellect). Only a select few people are capable of progressing to this level.

All of these steps actually signify travelling along the same path to leave potential and join reality. Each stage that comes after the one before it has the potential to be better than the one before, therefore advancing through them entails gradings of intensity and going from weakness to strength. The points of the “line of development” and the “line of human life”, which are constructed on the basis of the principles of graded existence and trans-substantial motion, respectively, are made up of the collection of these stages.

It is crucial to understand that moving on to the next stage does not mean leaving the one before it behind; rather, each higher stage always embodies and encompasses the lower stages that came before it. According to the rule presented here, every strong existence, in the gradation of existence, encompasses all earlier, weaker existential stages. Mulla Sadra disagrees with philosophers like the Peripatetics who view the soul as a static substance that does not undergo trans-substantial mobility and remains in the same state from the start of life to the end. He obviously disagrees with those who hold that the soul and body are entirely distinct, such as Descartes.

Mulla Sadra, like other Muslim thinkers, holds that the soul is immaterial, but not in the way that his preceding schools of thought intended. According to him, the soul’s immateriality comes gradually as a result of its ascent and development, as well as, in his own words, as a result of its trans-substantial mobility. Although this motion results in the body’s senility and destruction, it is a motion toward rationality in the soul and grows stronger and more active every day. The evolved soul eventually transforms into the “abstract intellect” and lives in a place that is more attractive than the material one after separating from the body and ceasing to need it.

The basis of Descartes’ theory is “the real distinction between the substance of the soul and body,” while the basis of Mulla Sadra’s theory is “the corporeality of contingency and the spirituality of subsistence in relation to the soul”. The dualism of Descartes caused his philosophical system to fall apart, and the new theory of Mulla Sadra regarding the soul resulted in the development of a philosophical proof for showing physical resurrection.

Mulla Sadra portrays the human soul and its station in a way that is free from the typical contradictions of philosophical traditions in this area. Mulla Sadra bases his depiction of the human soul and its station on the doctrines of principality of existence, motion in substance, bodily origination, and the spiritual subsistence of the soul. At the same time, he creates a new window into human existence based on the Book and tradition through which the existential aspects of the human are perceived in correspondence and as being identical to the entirety of the universe. Mulla Sadra has utilised the Peripatetic and Illuminationist traditions of his forebears in this way, but he has also created unique and powerful innovations.

In his philosophical psychology, Mullâ Sadrâ faced problems relating to the afterlife of the human soul. There were four competing ideas on this topic at the time: (a) The soul dies with the body when it passes away; (b) Reincarnation or transmigration of the soul, attributed to Pythagoras and Plato and upheld by Ikhwân al-Safâ, some Ismâîlî philosophers, and Qutb al-Dîn al-Shîrâzî, the commentator on Hikmat al-Ishrâq of Suhrawardî; (c) The elemental physical body will be revived with the soul on the Day of Resurrection and will be physically compensated for the soul’s actions. The soul will remain in the physical tomb and experience a foretaste of happiness or chastisement depending on its deeds. It is referred to as ma’âd jismanî in the holy language of Islam (bodily resurrection). Al-Ghazzâlî was pivotal among the Mutakallimun (theologians) who upheld this interpretation of the Islamic religiously revealed texts; and (d) Avicenna and the Muslim Peripatetic philosophers upheld the belief that the resurrection will only be a spiritual resurrection (ma’âd ruhânî) and that the recompense will also be spiritual.

On the basis of his philosophical presuppositions, which deal with his concept of matter and form, different levels of body, independence of the imaginative faculty of the soul, the imaginal world (‘âlam al-mithâl) or barzakh (the intermediate world), substantial motion of the soul, and oneness and gradation of being, Mullâ Sadrâ demonstrated the inadequacy of all the aforementioned positions regarding the posthumous state of the psychic non-physical being and its bodily resurrection. Along with the Qur’an, Hadîth, and the sayings of the Shi’ite Imams, we find that he also reworked the writings of Ibn ‘Arab and Suhraward on this subject. He also drew on a number of modern fields of knowledge, such as psychology, medicine, religious experience of death, and his own personal spiritual experience. As a result, his theory of resurrection transcends opposing theological interpretations, and it may be used to interpret religious writings that address this topic and the afterlife.