1) His Biography

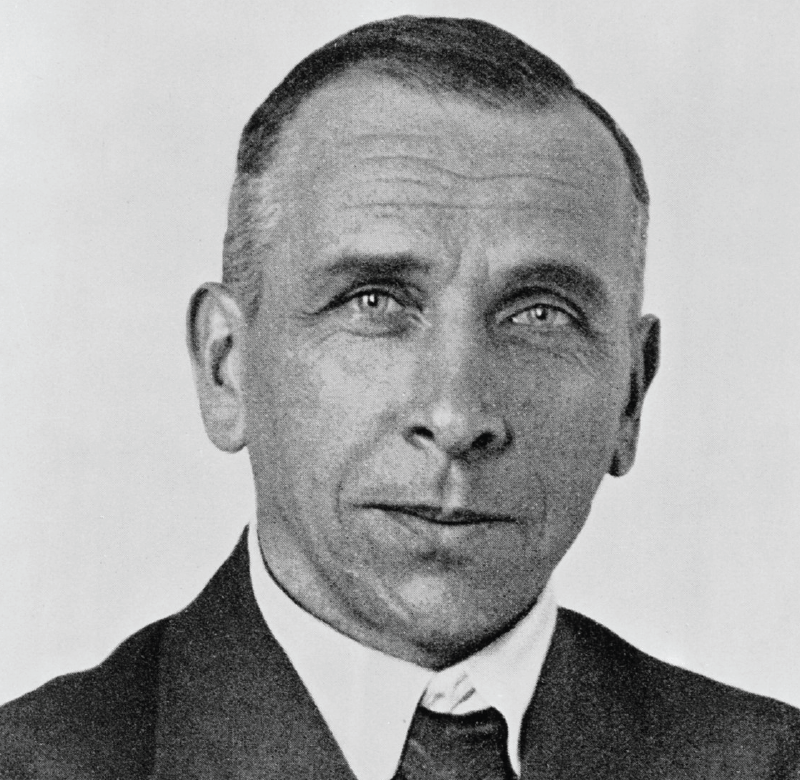

Alfred Wegener, born on November 1, 1880, in Berlin, Germany, was a pioneering geophysicist, meteorologist, and polar researcher whose groundbreaking ideas about continental drift revolutionised the field of geology. Wegener was the youngest of five children born to Richard Wegener, a theologian, and Anna Wegener. His early life was marked by a deep fascination with the natural world, which was nurtured by his father’s intellectual pursuits and his own curiosity about science. Wegener’s keen interest in understanding the Earth’s processes would eventually lead him to challenge some of the most entrenched scientific beliefs of his time.

Wegener’s academic journey began at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin, where he initially studied astronomy. He earned his PhD in 1905 with a thesis on the motion of water vapour in the atmosphere, demonstrating an early inclination towards interdisciplinary research. Although trained as an astronomer, Wegener’s interests quickly shifted towards the fields of meteorology and geophysics. He was particularly intrigued by the Earth’s atmosphere and the various forces that shaped the planet’s surface. This shift in focus would ultimately set the stage for his later work on continental drift.

Wegener’s career as a scientist was marked by a strong commitment to fieldwork and exploration. In 1906, he participated in his first major expedition to Greenland, organised by the Royal Danish Geographical Society. The expedition aimed to study polar weather conditions and glacial activity, areas of significant interest to Wegener. During this expedition, he and his brother Kurt set a new world record for the longest continuous balloon flight, lasting 52 hours. This achievement not only underscored Wegener’s adventurous spirit but also highlighted his innovative approach to scientific research, combining direct observation with practical experimentation.

After returning from Greenland, Wegener took up a teaching position at the University of Marburg, where he continued to refine his theories about the Earth’s atmosphere. However, his most significant contribution to science began to take shape during this period, as he began to develop his theory of continental drift. Wegener was struck by the apparent fit between the coastlines of South America and Africa and began to gather evidence to support the idea that these continents were once connected. He meticulously compiled data from various scientific disciplines, including geology, paleontology, and climatology, to build a case for his revolutionary hypothesis that the continents were not fixed but had moved over geological time.

Wegener’s academic career was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I in 1914. He served as a lieutenant in the German Army, where he was wounded twice and subsequently assigned to a weather station. Despite the challenges of wartime, Wegener remained committed to his scientific pursuits, continuing to develop his ideas about continental drift. His time at the weather station allowed him to conduct further research on atmospheric processes, deepening his understanding of the Earth’s dynamic systems. In 1915, during a break from military service, Wegener published the first edition of his groundbreaking book, Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane (The Origin of Continents and Oceans), in which he laid out his theory of continental drift.

After the war, Wegener returned to academia, accepting a position at the University of Hamburg. During this period, he continued to expand upon his continental drift theory, publishing several more editions of his book with updated evidence and arguments. Despite his growing body of evidence, Wegener faced significant opposition from the scientific community, primarily due to his inability to provide a plausible mechanism for the movement of continents. Many geologists of the time adhered to the prevailing belief that the Earth’s crust was static and immovable, making Wegener’s ideas seem radical and unconvincing. Nevertheless, Wegener remained steadfast in his beliefs, convinced that his observations and evidence would eventually be validated.

In 1924, Wegener was appointed as a professor of meteorology and geophysics at the University of Graz in Austria, where he continued his research and teaching. His passion for polar research led him to return to Greenland several times, where he conducted extensive studies on glaciology and climate. These expeditions were not without risk; Wegener faced numerous challenges, including harsh weather conditions, limited resources, and the constant threat of frostbite and other injuries. His commitment to understanding the natural world, even under such extreme conditions, demonstrated his dedication to scientific discovery and his adventurous spirit.

Wegener’s final expedition to Greenland in 1930 would be his most ambitious and ultimately, his last. He aimed to establish a permanent meteorological station in the interior of the Greenland ice sheet to gather long-term climate data. Unfortunately, during this expedition, Wegener and his companion, Rasmus Villumsen, perished while attempting to deliver supplies to a remote weather station. Their bodies were not found until the following year, with Wegener’s final resting place marked by a simple cross on the ice. His death at the age of 50 was a significant loss to the scientific community, but his ideas would continue to resonate and inspire future generations of scientists.

2) Main Works

The Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere (1911):

This book, co-authored with his brother Kurt Wegener, represents Alfred Wegener’s significant contribution to meteorology and thermodynamics. In this work, Wegener delves into the principles governing atmospheric processes, including the dynamics of air masses, heat transfer, and the thermodynamics of weather systems. The book provides a foundational understanding of how temperature and pressure variations influence weather patterns. It also explores how these atmospheric conditions can lead to phenomena such as storms, precipitation, and climate variability.

The publication of “The Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere” was a pioneering effort to combine physics with meteorology, offering a more comprehensive understanding of weather and climate. This work laid the groundwork for future studies in atmospheric science, and its influence can still be seen in modern meteorological research. It demonstrated Wegener’s ability to apply mathematical rigor and physical principles to atmospheric studies, which would later underpin his approach to developing the theory of continental drift.

The Origin of Continents and Oceans (1915):

Perhaps Wegener’s most famous work, “The Origin of Continents and Oceans” is where he first formally presented his revolutionary theory of continental drift. In this book, Wegener proposed that continents were once part of a giant supercontinent, which he named “Pangaea,” meaning “all lands.” According to his hypothesis, this supercontinent began to break apart about 200 million years ago, and the continents drifted to their current positions. Wegener supported his theory with several lines of evidence, including the fit of continental coastlines, the distribution of fossils, and geological similarities across continents.

Although initially controversial and widely rejected by the scientific community, “The Origin of Continents and Oceans” is now regarded as a groundbreaking work in the field of geology. Wegener’s theory laid the foundation for the development of plate tectonics, which is now the accepted explanation for the movement of the Earth’s crust. Despite the initial skepticism, Wegener’s work fundamentally changed the way scientists understand the Earth’s geological history and processes, highlighting his visionary approach to Earth sciences.

Climate and Continental Drift (1924):

In “Climate and Continental Drift,” Alfred Wegener expanded on his ideas about the mobility of continents by linking them to historical climate changes. He suggested that the shifting positions of continents had a significant impact on global climate patterns over geological time scales. Wegener explored how the arrangement of continents affected ocean currents, atmospheric circulation, and the distribution of heat across the planet, which in turn influenced climate zones and the evolution of life on Earth.

This work was significant because it broadened the implications of continental drift beyond just geology, incorporating climate science and biology. Wegener argued that the movement of continents could explain the historical changes in Earth’s climate, such as ice ages and warm periods. Although some of his specific ideas were later revised, “Climate and Continental Drift” demonstrated Wegener’s interdisciplinary approach and his ability to integrate different scientific fields into a cohesive theory.

Expedition to Greenland (1930):

Alfred Wegener’s “Expedition to Greenland” was a detailed account of his final and most ambitious expedition to the Arctic. This work provided a comprehensive description of the scientific objectives, methodologies, and findings of the expedition, which aimed to collect meteorological and glaciological data from the remote interior of Greenland. Wegener’s team faced severe challenges, including extreme cold, treacherous ice, and logistical difficulties, but they managed to gather valuable data that contributed to a better understanding of polar climates and glacial dynamics.

The expedition is particularly notable because it was during this journey that Wegener lost his life in November 1930. Despite the tragic outcome, the data collected during the expedition had a lasting impact on polar research. Wegener’s commitment to scientific exploration and his dedication to advancing knowledge, even at great personal risk, solidified his reputation as a pioneering figure in geophysics and meteorology. “Expedition to Greenland” serves as a testament to his adventurous spirit and scientific rigor.

The Formation of Ice on Rivers and Lakes (1923):

In this work, Wegener focused on the physical processes involved in the formation of ice on freshwater bodies. He explored how temperature, water currents, and wind conditions contribute to the freezing process, and he provided detailed observations of ice formation on rivers and lakes. Wegener’s research included experiments and field observations that helped elucidate the dynamics of ice formation, growth, and break-up, contributing to the broader understanding of freshwater ice phenomena.

“The Formation of Ice on Rivers and Lakes” was significant because it provided practical insights that were relevant to navigation, infrastructure, and winter transportation. Wegener’s work in this area also helped lay the groundwork for subsequent studies on ice physics, particularly in the context of climate research and hydrology. This book highlights Wegener’s diverse scientific interests and his ability to conduct research across different fields, from atmospheric science to hydrology, always maintaining a high standard of scientific inquiry.

3) His Contribution to Geology

Alfred Wegener’s contributions to geology are both profound and far-reaching, with his most notable achievement being the formulation of the theory of continental drift. Proposed in 1912 and later elaborated in his 1915 book, “The Origin of Continents and Oceans,” Wegener’s theory fundamentally challenged the prevailing geological paradigms of his time. Prior to Wegener, the dominant view held that the Earth’s continents were static and had remained in fixed positions throughout geological history. Wegener, however, argued that the continents were once part of a single supercontinent, Pangaea, which gradually fragmented and drifted apart to their present locations. This idea revolutionised geological science by suggesting that the Earth’s surface was dynamic and constantly evolving.

Wegener’s theory was primarily based on several key pieces of evidence that he meticulously compiled from various fields of study, including geology, palaeontology, and climatology. One of his most compelling pieces of evidence was the remarkable fit of the coastlines of South America and Africa, which appeared to align perfectly when positioned together. This observation suggested that the continents might have once been joined. Furthermore, Wegener noted the similarity of fossil records on different continents; for instance, identical species of ancient plants and animals were found in both South America and Africa, separated by the vast Atlantic Ocean. This phenomenon could only be explained if the continents had once been connected, allowing species to migrate freely between them.

In addition to fossil evidence, Wegener also highlighted geological similarities between continents. He observed that the rock formations on the eastern coast of South America matched those on the western coast of Africa, further supporting his hypothesis of a once-united supercontinent. These geological formations included mountain ranges and strata that were remarkably similar in age and structure. Such similarities would be difficult to explain if the continents had always been separated by vast oceans. Moreover, Wegener pointed out the presence of glacial deposits in regions that are currently tropical, suggesting that these areas had once been located in much colder climates. This evidence of past climates being inconsistent with the current geographical positions of the continents lent further support to his theory.

Despite the compelling evidence he presented, Wegener’s theory was met with widespread scepticism and resistance from the geological community of his time. One of the primary reasons for this resistance was Wegener’s inability to provide a convincing mechanism for how the continents could move. The scientific consensus at the time was that the Earth’s crust was solid and immovable, making the idea of drifting continents seem implausible. Furthermore, Wegener’s background in meteorology rather than geology led many to dismiss his ideas as the work of an outsider lacking the necessary expertise. As a result, continental drift was largely rejected by mainstream geologists during Wegener’s lifetime.

However, Wegener’s contributions to geology extended beyond his theory of continental drift. He also made significant strides in understanding the Earth’s atmospheric conditions, which indirectly supported his geological theories. His work on polar research and glaciology, particularly his expeditions to Greenland, helped refine ideas about past climatic conditions on Earth. These studies on glacial movements and their geological impacts provided additional evidence for his hypothesis, particularly in explaining the presence of glacial deposits found on multiple continents that are now widely separated by oceans.

It was not until the 1950s and 1960s, several decades after Wegener’s death, that his theory of continental drift gained widespread acceptance. This change in attitude was primarily due to the discovery of new evidence related to the structure and dynamics of the Earth’s crust. The development of the theory of plate tectonics provided the much-needed mechanism that Wegener’s theory lacked. It explained that the Earth’s lithosphere is divided into several plates that float on the semi-fluid asthenosphere beneath them. This discovery validated Wegener’s idea that continents could move and provided a more detailed understanding of the forces driving these movements, such as mantle convection.

Alfred Wegener’s pioneering ideas laid the groundwork for modern geology. By challenging the long-standing views of his contemporaries, he opened the door to new ways of thinking about the Earth’s dynamic nature. The eventual acceptance of his theory of continental drift marked a paradigm shift in geology, leading to the development of the comprehensive theory of plate tectonics, which is now the cornerstone of modern geological science. Wegener’s work exemplifies the importance of cross-disciplinary thinking and the willingness to challenge established scientific norms, paving the way for future discoveries and advancements in our understanding of the Earth.

4) Theory of Continental Drift

Alfred Wegener’s theory of continental drift, first proposed in 1912 and detailed in his seminal 1915 book, The Origin of Continents and Oceans, revolutionised the field of geology by challenging the prevailing belief that continents were static and immovable. Wegener suggested that continents were once part of a giant supercontinent called Pangaea, which began to break apart approximately 200 million years ago. According to his theory, the continents slowly drifted to their present positions over millions of years, driven by forces not yet understood in his time. This groundbreaking hypothesis laid the foundation for the later development of the theory of plate tectonics, which provides a comprehensive explanation of the dynamic processes that shape the Earth’s surface.

Wegener’s initial inspiration for his theory came from observing the remarkable jigsaw-puzzle fit of the coastlines of South America and Africa. He noticed that these continents seemed to fit together almost perfectly, suggesting that they might have once been connected. This observation led him to wonder if other continents could also have been part of a larger landmass that had subsequently drifted apart. As he delved deeper into his research, Wegener compiled extensive evidence from various scientific disciplines, including geology, paleontology, climatology, and biology, to support his hypothesis of continental drift.

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence Wegener presented was the striking similarity of fossil records across continents now separated by vast oceans. For example, he noted the presence of identical species of prehistoric plants and animals, such as the extinct reptile Mesosaurus and the ancient fern Glossopteris, on continents as far apart as South America, Africa, India, and Antarctica. These findings suggested that these landmasses were once connected, allowing species to migrate freely between them before being separated by the formation of oceans. Additionally, Wegener pointed out that rock formations on different continents were remarkably similar in age, type, and structure, further supporting his theory that the continents had once been part of a single landmass.

Wegener also used climatic evidence to bolster his theory. He observed the presence of glacial deposits and striations—scratches left by glaciers—in regions that are now tropical or temperate, such as India, Africa, and South America. These geological features could not be explained by the current positions of the continents. However, if these landmasses had once been located closer to the polar regions, the evidence of past glaciation made perfect sense. Wegener argued that the drifting of continents to their current positions could explain these otherwise puzzling climatic anomalies.

Despite the compelling evidence Wegener provided, his theory of continental drift was met with considerable scepticism from the scientific community. One of the primary reasons for this resistance was his inability to propose a convincing mechanism that could explain how the continents moved. At the time, most geologists believed that the Earth’s crust was solid and immovable. Wegener suggested that the continents ploughed through the oceanic crust like icebergs through water, driven by forces such as centrifugal force and tidal drag. However, these ideas were not convincing to many geologists, who found them inadequate to explain the enormous forces required to move entire continents. As a result, Wegener’s theory was largely dismissed by mainstream science during his lifetime.

It was not until the mid-20th century that new discoveries provided the missing pieces to support Wegener’s theory. The development of the theory of plate tectonics in the 1950s and 1960s provided the mechanism that Wegener’s theory had lacked. Scientists discovered that the Earth’s lithosphere is broken into several large plates, including both continental and oceanic crust, that float on the semi-fluid asthenosphere beneath them. This discovery showed that the continents are not independent entities but are part of larger tectonic plates that move due to mantle convection—heat-driven currents within the Earth’s mantle. This explained how continents could drift and accounted for various geological phenomena, such as earthquakes, volcanic activity, and mountain-building processes, which were not well understood before.

The theory of plate tectonics validated Wegener’s ideas about continental movement and transformed our understanding of Earth’s dynamic nature. With the acceptance of plate tectonics, many of Wegener’s observations and predictions were finally recognised as accurate and insightful. His ideas about the past configuration of continents and the existence of ancient supercontinents like Pangaea became foundational to the fields of geology, paleoclimatology, and evolutionary biology. Today, the theory of plate tectonics is considered one of the unifying theories in Earth science, explaining a wide range of geological phenomena and shaping our understanding of the Earth’s history and structure.

5) His Legacy

Alfred Wegener’s legacy in the field of Earth sciences is both profound and enduring, characterised by his revolutionary ideas and his role in laying the groundwork for modern geology. His most significant contribution, the theory of continental drift, fundamentally altered our understanding of the Earth’s surface and its dynamic nature. Although his ideas were initially met with scepticism and opposition, they eventually paved the way for the development of the theory of plate tectonics, which is now widely accepted as the foundational framework for understanding geological processes. Today, Wegener is celebrated as a visionary thinker who dared to challenge established scientific norms and whose work continues to influence the study of Earth’s history and structure.

Wegener’s theory of continental drift, first proposed in the early 20th century, introduced the radical concept that continents were not fixed in place but instead moved across the Earth’s surface over geological time. This idea was groundbreaking because it challenged the long-held belief that the continents and ocean basins were permanent and immovable features. Although Wegener lacked a convincing mechanism to explain how the continents could move, his extensive compilation of evidence from various scientific fields—such as geology, paleontology, climatology, and biology—demonstrated his commitment to a multidisciplinary approach. This evidence included the matching coastlines of continents like South America and Africa, similar fossil records across different continents, and geological formations that appeared to continue across continental boundaries. These observations laid the foundation for future scientific exploration and discovery.

Wegener’s legacy is not just limited to his contributions to geology; he also had a significant impact on the broader scientific community by promoting the importance of interdisciplinary research. His work highlighted the value of synthesising information from different scientific fields to build a comprehensive understanding of natural phenomena. This approach is now a cornerstone of scientific inquiry, particularly in Earth sciences, where the integration of data from geology, oceanography, atmospheric science, and biology is essential for understanding complex processes such as climate change, plate tectonics, and ecosystem dynamics. Wegener’s example continues to inspire scientists to think beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries and seek out connections that can lead to new insights and discoveries.

The eventual acceptance of Wegener’s ideas was greatly facilitated by technological advancements and new scientific discoveries in the mid-20th century. The advent of seafloor mapping technology and the discovery of mid-ocean ridges provided concrete evidence for seafloor spreading, a key mechanism that Wegener’s theory lacked. The development of paleomagnetic studies also offered crucial support, showing that the Earth’s magnetic field had reversed many times throughout history, leaving a record in the rocks that could be matched across different continents. These findings, along with the theory of plate tectonics, validated Wegener’s vision of a dynamic Earth and demonstrated the accuracy of his predictions regarding the past configuration of continents and the movement of tectonic plates.

Wegener’s legacy also extends to his contributions to polar research and climatology. His expeditions to Greenland, where he conducted extensive studies on glaciology and atmospheric conditions, provided valuable data that enhanced our understanding of polar environments and climate dynamics. His work in these fields helped to establish the importance of polar research in understanding global climate patterns and laid the groundwork for future studies on climate change. Wegener’s interdisciplinary approach and his willingness to venture into challenging and unexplored areas of research continue to inspire scientists today, particularly those working in polar and climate sciences.

Moreover, Wegener’s legacy is a testament to the power of perseverance in the face of adversity. During his lifetime, his ideas were widely criticised and dismissed by many in the scientific community, largely because he was unable to provide a plausible mechanism for continental movement. However, Wegener remained steadfast in his belief in his theory and continued to refine and defend his ideas until his untimely death in 1930. His persistence and dedication to scientific inquiry, even in the face of scepticism, serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of tenacity and open-mindedness in the pursuit of scientific truth. His story encourages scientists to remain curious and bold, to question established norms, and to pursue innovative ideas despite potential opposition.

Today, Alfred Wegener is regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of Earth sciences. His work has inspired generations of geologists, climatologists, and other scientists to explore the dynamic processes that shape our planet. The acceptance of his ideas and their integration into the theory of plate tectonics have provided a unifying framework that has transformed our understanding of geological processes, from the formation of mountain ranges to the occurrence of earthquakes and volcanic activity. Wegener’s legacy lives on in the countless studies and scientific advancements that continue to build upon his groundbreaking ideas, ensuring that his contributions to science will be remembered and celebrated for generations to come.