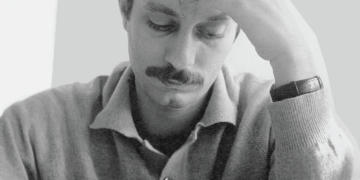

Thomas Huxley

1) His Biography

Thomas Henry Huxley, often referred to as “Darwin’s Bulldog,” was a prominent 19th-century British naturalist and biologist. Born on May 4, 1825, in Ealing, London, Huxley’s early life was marked by financial struggles, as his family faced limited means. Despite these challenges, he displayed an early aptitude for the natural sciences, fostering a passion that would shape his illustrious career.

Huxley’s educational journey began at Charing Cross Hospital Medical School, where he studied medicine and anatomy. His interest in the natural world led him to the Royal School of Mines, where he delved into the emerging field of paleontology. His early contributions in this area laid the foundation for his later acclaim. Huxley’s insatiable curiosity and dedication to scientific inquiry earned him recognition within academic circles, establishing him as a leading figure in Victorian science.

Throughout his life, Huxley’s work extended beyond the confines of academia. His engagement with the scientific community and the wider public solidified his reputation as a fervent advocate for the evolutionary theories proposed by Charles Darwin. Huxley’s commitment to scientific rigour, coupled with his eloquence as a speaker and writer, made him a key proponent of the theory of evolution, defending it against contemporary criticisms.

Huxley’s legacy extends to his contributions as a teacher and lecturer, shaping the minds of future generations of scientists. His impact on the scientific community, both through his research and his advocacy, cements his place as a key figure in the history of biology and evolutionary thought. As we delve into the intricacies of Huxley’s biography, we gain insight into the life of a man who not only shaped the scientific landscape of his time but left an enduring mark on the trajectory of evolutionary biology.

2) Main Works

On the Origin of Species – Review (1859):

One of Huxley’s notable works includes his review of Charles Darwin’s groundbreaking book, “On the Origin of Species.” In this comprehensive analysis, Huxley not only supported Darwin’s revolutionary ideas on evolution but also eloquently defended the scientific merits of the theory. His endorsement played a crucial role in popularising Darwinian evolution within the scientific community.

Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature (1863):

Huxley’s “Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature” is a seminal work in anthropology and paleontology. In this book, he presents compelling evidence for the evolutionary relationship between humans and apes, challenging prevailing beliefs about the distinctiveness of humans within the animal kingdom. This work solidified Huxley’s reputation as a leading advocate for the evolutionary perspective on human origins.

Lectures on Evolution (1868):

Huxley’s lectures on evolution, delivered at various institutions, encapsulated his passionate advocacy for Darwinian ideas. These lectures, often engaging and accessible to a broader audience, played a pivotal role in disseminating evolutionary concepts beyond academic circles. Huxley’s ability to communicate complex scientific ideas to diverse audiences contributed significantly to the acceptance of evolutionary theory.

The Crayfish (1879):

Huxley’s interest in comparative anatomy is evident in his work on “The Crayfish.” This detailed study explores the anatomy and physiology of these crustaceans, showcasing his meticulous approach to biological research. By examining the intricacies of a specific organism, Huxley contributed valuable insights to the broader field of zoology.

Science and Culture (1881):

In “Science and Culture,” Huxley addresses the relationship between scientific knowledge and broader societal concerns. He emphasises the importance of scientific education and the role of scientific thinking in shaping a progressive and informed society. This work reflects Huxley’s commitment to the integration of science into public discourse.

Prolegomena (1868):

Huxley’s “Prolegomena” serves as an introductory text to the study of biology. This work outlines the principles of biological science, providing a framework for understanding the complexities of the natural world. Huxley’s clarity of thought and dedication to scientific education are evident in this foundational piece.

3) Main Themes

Evolution and Natural Selection:

Thomas Huxley’s exploration of evolution and natural selection stands as a cornerstone of his intellectual legacy. Huxley’s in-depth analysis of Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” went beyond mere endorsement; he dissected the mechanisms of natural selection and their implications for the understanding of life’s diversity. Huxley’s original contribution lies in his elucidation of the concept of “adaptive radiation,” a term he coined to describe the divergence of species from a common ancestor to occupy different ecological niches. This concept highlighted the dynamic relationship between organisms and their environments, emphasising adaptation as a driving force in evolutionary processes.

In comparison to other contemporary thinkers, Huxley engaged in a notable debate with Richard Owen, a prominent anatomist. While Owen acknowledged the reality of evolution, he rejected the role of natural selection, proposing a teleological view. Huxley’s emphasis on empirical evidence and the observable consequences of natural selection, as opposed to Owen’s more speculative approach, underscored the rigour and empirical foundation of Huxley’s contributions. Additionally, Huxley’s discussions with Alfred Russel Wallace, another proponent of evolution, provided a platform for refining evolutionary theories, enriching the discourse on the subject.

Human Evolution and Anthropology:

Huxley’s work extended to the realm of human evolution, challenging prevailing beliefs about the uniqueness of humans within the animal kingdom. In “Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature,” Huxley presented a comparative anatomical study, demonstrating the anatomical similarities between humans and apes. His meticulous examination of fossil evidence and anatomical structures provided a compelling case for the evolutionary connection between humans and other primates.

Huxley’s original contribution in this domain was the establishment of the “Pithecometra principle,” asserting a common ancestry for humans and apes. This principle, grounded in comparative anatomy, served as a foundational concept in human evolutionary studies. Huxley’s views contrasted with those of Louis Agassiz, a contemporary naturalist who advocated for the separate creation of humans and rejected evolutionary ideas. Huxley’s emphasis on empirical evidence and his rigorous anatomical studies contributed significantly to the acceptance of human evolution within the scientific community.

Science and Society:

A central theme in Huxley’s writings was the relationship between science and society. In “Science and Culture,” he addressed the societal implications of scientific knowledge, advocating for the integration of scientific thinking into broader cultural and educational contexts. Huxley argued that scientific education was essential for fostering a rational and informed society, emphasising the importance of disseminating scientific knowledge to the public.

Huxley’s original contribution lies in his articulation of the concept of “scientific naturalism,” which advocated for the application of scientific principles to all aspects of human life. This perspective contrasted with the views of John Henry Newman, who believed in the autonomy of religious and scientific domains. Huxley’s defence of scientific naturalism positioned him as a champion of reason and empirical inquiry, contributing to the ongoing dialogue about the role of science in shaping societal values.

Thomas Huxley’s exploration of these themes not only shaped the intellectual landscape of his time but also laid the groundwork for subsequent developments in evolutionary biology, anthropology, and the philosophy of science. His original contributions and engagements with contemporaries enriched these themes with nuanced perspectives, fostering a deeper understanding of the intricate interplay between science, evolution, and society.

Scientific Method and Empiricism:

At the core of Huxley’s contributions is his commitment to the scientific method and empiricism. Huxley championed a rigorous and empirical approach to scientific inquiry, insisting on the importance of observable evidence and experimentation. In “Prolegomena,” he outlined the principles of biological science, advocating for the application of empirical methods to the study of living organisms.

Huxley’s original contribution was his emphasis on comparative anatomy as a tool for understanding evolutionary relationships. Through detailed anatomical studies of diverse organisms, he provided empirical support for evolutionary theory. This approach distinguished him from idealist philosophers like Immanuel Kant, who focused on conceptual frameworks rather than empirical observation. Huxley’s dedication to empiricism not only strengthened the scientific basis of biology but also influenced the broader scientific community’s approach to research and investigation.

Education and Popularization of Science:

Huxley’s commitment to education and the popularization of science is a theme that permeates his works. Recognizing the importance of disseminating scientific knowledge to a wider audience, he delivered numerous lectures on evolution at various institutions. His lectures, compiled in works like “Lectures on Evolution,” were designed to make complex scientific concepts accessible to a broader audience, bridging the gap between academia and the public.

Huxley’s original contribution in this realm was his skill in communicating scientific ideas to diverse audiences. His clarity of expression and engaging speaking style made complex topics understandable to non-specialists. In contrast to more esoteric writing styles of some contemporaries, such as Thomas Carlyle, Huxley’s efforts aimed to bring scientific knowledge to the forefront of public discourse. His advocacy for scientific education played a pivotal role in shaping public perceptions of science, influencing the trajectory of science communication in the years to come.

4) Huxley as Anthropologist

Thomas Huxley’s contributions to anthropology marked a significant facet of his intellectual legacy. While he is often celebrated for his role in evolutionary biology, his forays into anthropology, particularly in the study of human evolution, showcase the breadth of his scientific interests. In “Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature” (1863), Huxley conducted a pioneering examination of comparative anatomy, dissecting the anatomical similarities between humans and other primates.

Huxley’s original contribution in anthropology was the formulation of the “Pithecometra principle,” a concept asserting a common ancestry for humans and apes. Through meticulous anatomical studies and fossil evidence, he argued that the anatomical resemblances observed between humans and apes could be best explained by a shared evolutionary lineage. This principle challenged prevailing notions of human exceptionalism and paved the way for a more integrated understanding of human evolution within the broader context of the animal kingdom.

In contrast to some contemporary thinkers, such as Louis Agassiz, who rejected evolutionary ideas and advocated for the special creation of humans, Huxley’s empirical approach and commitment to evidence-based reasoning positioned him as a key figure in advancing the acceptance of human evolution. His emphasis on the scientific method and rigorous anatomical studies contributed to the establishment of anthropology as a discipline grounded in empirical observation.

Furthermore, Huxley engaged in debates that shaped the trajectory of anthropological inquiry during his time. His debates with other scientists, including Richard Owen, exemplified the intellectual clashes that characterised Victorian science. Huxley’s debates with Owen, who acknowledged the reality of evolution but rejected natural selection, underscored Huxley’s commitment to Darwinian principles. These exchanges not only highlighted the nuances within the scientific community but also showcased Huxley’s role as a vocal advocate for the empirical foundations of anthropological research.

5) Huxley on the Theory of Evolution

Thomas Huxley’s stance on the theory of evolution, particularly in relation to Charles Darwin’s groundbreaking work, “On the Origin of Species,” played a pivotal role in shaping the narrative and acceptance of evolutionary ideas in the scientific community. Huxley, often referred to as “Darwin’s Bulldog,” was a staunch defender of Darwin’s theory, vigorously advocating for the scientific merits of evolution through natural selection.

In his extensive review of “On the Origin of Species” published in 1859, Huxley not only expressed his support for Darwin’s revolutionary ideas but also provided a detailed and comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms underlying natural selection. His elucidation of the concept of natural selection went beyond a mere endorsement, demonstrating a deep understanding of the biological processes at play. Huxley’s original contribution lay in his ability to communicate these complex ideas with clarity and rigour, making the theory of evolution more accessible to both scientists and the broader public.

One of the key aspects of Huxley’s support for evolution was his emphasis on empirical evidence. Huxley, a strong advocate for the scientific method, insisted that any scientific theory must be grounded in observable and testable evidence. This emphasis on empirical validation distinguished him from contemporaries who might have been more speculative in their approach. Huxley’s commitment to empirical rigour bolstered the credibility of the theory of evolution and reinforced its standing as a scientifically robust framework.

Huxley’s engagement in public debates further showcased his dedication to defending the theory of evolution. Notably, his debates with Richard Owen, a prominent anatomist, highlighted the clash between evolutionary and non-evolutionary perspectives within the scientific community. Huxley’s articulate and persuasive arguments, firmly rooted in empirical evidence, countered the objections raised by Owen and other critics. These debates not only solidified Huxley’s reputation as a tenacious advocate for evolution but also contributed to the broader acceptance of Darwinian ideas within academic circles.

6) His Legacy

Thomas Huxley’s legacy is indelibly imprinted on the landscape of science, education, and the public understanding of evolution. As a tireless advocate for Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution through natural selection, Huxley’s influence reverberates through both the academic realm and the broader societal discourse.

Huxley’s most enduring legacy lies in his role as “Darwin’s Bulldog.” Through his articulate writings and passionate public lectures, he not only defended the theory of evolution but also played a pivotal role in disseminating its concepts to a wider audience. His commitment to empirical evidence and scientific rigour provided a solid foundation for the acceptance of evolutionary ideas within the scientific community, contributing to the transformation of biology into an empirical science.

In the field of anthropology, Huxley’s legacy endures in his contributions to the understanding of human evolution. By bridging the gap between humans and other primates through comparative anatomy, he laid the groundwork for a more integrated perspective on our place in the natural world. The Pithecometra principle, formulated by Huxley, continues to influence discussions on human evolution and the shared ancestry of humans and apes.

Furthermore, Huxley’s impact on education and the popularization of science remains profound. His lectures on evolution, compiled in works such as “Lectures on Evolution,” were instrumental in making complex scientific concepts accessible to a broader audience. Huxley’s emphasis on scientific education as a means to cultivate a rational and informed society resonates in ongoing discussions about the role of science in education and public discourse.

Beyond his specific contributions, Huxley’s legacy is intertwined with the broader cultural and intellectual shifts of his time. His engagement in public debates, particularly with figures like Richard Owen, showcased the clash between traditional and evolutionary perspectives. Huxley’s steadfast defence of empiricism and the scientific method influenced not only his contemporaries but also subsequent generations of scientists, shaping the trajectory of scientific inquiry.

7) Some Quotes

“The known is finite, the unknown infinite; intellectually we stand on an islet in the midst of an illimitable ocean of inexplicability.” – Thomas Huxley

“The great tragedy of Science—the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.” – Thomas Huxley

“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.” – Thomas Huxley

“The rung of a ladder was never meant to rest upon, but only to hold a man’s foot long enough to enable him to put the other somewhat higher.” – Thomas Huxley

“Science is simply common sense at its best, that is, rigidly accurate in observation, and merciless to fallacy in logic.” – Thomas Huxley