1) His Biography

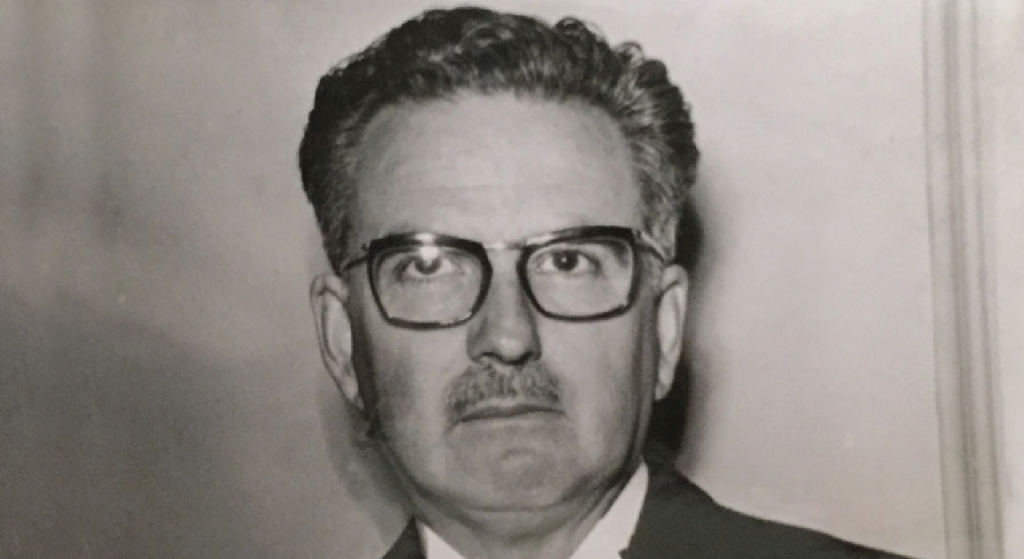

Julio Caro Baroja was born on 13 November 1914 in Madrid, into a distinguished and intellectually vibrant family that had a profound influence on his later work. He was the nephew of the celebrated novelist Pío Baroja and the painter and engraver Ricardo Baroja, and grew up in an environment that encouraged curiosity and creativity. His mother, Carmen Baroja Nessi, was also a writer and ethnographer, fostering in her son a love for culture, language, and the traditions of Spain. This familial atmosphere of intellectual exchange and artistic expression shaped Caro Baroja’s early worldview, imbuing him with a keen sensitivity to the intersections between history, folklore, and human behaviour.

Caro Baroja’s formal education began in Madrid, where he pursued studies in history, philology, and ethnology. He was a student of some of Spain’s most influential scholars of the time, including José Ortega y Gasset, whose philosophical ideas on culture and society left a lasting impression on him. After completing his studies at the University of Madrid, Caro Baroja immersed himself in fieldwork and research, drawn to the rural landscapes of the Basque Country and Navarre, regions whose customs and languages would become central to his academic career. His early exposure to diverse traditions and dialects led him to appreciate the complexity of Spanish identity, a theme that would define much of his later scholarship.

During the turbulent years of the Spanish Civil War, Caro Baroja’s intellectual pursuits were interrupted but not extinguished. Though the conflict devastated Spain’s cultural and academic institutions, it also intensified his resolve to document the traditional ways of life that were rapidly disappearing. In the post-war years, he began to publish his first major ethnographic and historical works, which demonstrated both meticulous scholarship and literary elegance. His approach combined empirical observation with a deep humanistic concern for the people whose stories he recorded—a balance that distinguished him from many of his contemporaries.

Caro Baroja was associated with the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), where he held a research position that allowed him to develop a vast array of studies in anthropology, history, linguistics, and folklore. His fieldwork was characterised by both breadth and depth: he examined everything from Basque mythology and witchcraft to the structure of Spanish family life and the customs of various regional communities. His work stood out for its interdisciplinarity; he refused to confine himself to the boundaries of any single academic field, believing that understanding a culture required attention to its history, language, and daily practices alike.

Over the course of his career, Caro Baroja produced more than fifty books and countless essays, each reflecting his distinctive synthesis of ethnography, history, and philology. His writings often explored the tension between modernity and tradition, and he was particularly concerned with how industrialisation, centralised state power, and cultural homogenisation threatened the diversity of local Spanish identities. In his studies, such as Las brujas y su mundo (The World of the Witches), he examined folklore and superstition not as irrational relics but as expressions of historical and social conditions. Through such works, he sought to restore dignity and meaning to cultural forms that were often dismissed by urban intellectuals.

Caro Baroja’s scholarly reputation extended beyond Spain, earning him recognition in international circles of anthropology and history. He was invited to lecture at universities across Europe and America, where his nuanced understanding of cultural continuity and change attracted considerable attention. His perspective was distinctly Mediterranean, rooted in the unique blend of classical heritage, religious tradition, and local diversity that defined Iberian civilisation. Yet, his insights also resonated with broader debates in anthropology concerning identity, community, and the processes of cultural transformation.

Despite his academic acclaim, Caro Baroja remained deeply connected to the land and people of northern Spain. He lived much of his life in Bera de Bidasoa, a small Basque town where he continued to conduct fieldwork and write prolifically. This rural setting provided both inspiration and refuge, allowing him to observe the gradual erosion of traditional lifeways under the pressures of modernity. Until his death on 18 August 1995, he remained a prolific writer and a passionate defender of cultural plurality. His legacy endures not only through his extensive publications but also through the enduring respect he commands as one of Spain’s most original and humane intellectuals.

2) Main Works

Las brujas y su mundo (The World of the Witches, 1961)

This is perhaps Caro Baroja’s most renowned work and a cornerstone in the study of European witchcraft. Drawing upon archival documents, trial records, and ethnographic material, he examines the social, psychological, and cultural dimensions of witchcraft in early modern Spain. Rather than treating witches as mere figures of superstition, Caro Baroja situates them within the broader context of persecution, religious reform, and the anxieties of rural communities. The book highlights how accusations of witchcraft reflected deeper conflicts—between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, authority and dissent, and rationality and fear.

Los pueblos de España (The Peoples of Spain, 1946)

In this seminal ethnographic work, Caro Baroja presents a comprehensive portrait of the cultural and linguistic diversity of Spain. He explores regional differences in social organisation, economic activities, and symbolic practices, showing how geography and history have shaped the identities of various communities. The book rejects the notion of a monolithic Spanish culture, instead celebrating the multiplicity of local traditions and ways of life. Its historical scope and ethnological precision make it one of the most influential studies of Spanish society in the twentieth century.

La hora navarra del XVIII: Personajes, familias, instituciones (Navarre’s Eighteenth-Century Moment: Figures, Families, Institutions, 1969)

In this detailed historical study, Caro Baroja reconstructs the intellectual, economic, and political life of eighteenth-century Navarre. He focuses on the region’s prominent families and their interactions with broader Spanish and European currents of thought. By tracing local developments against the backdrop of Enlightenment ideals, he reveals the interplay between provincial and metropolitan dynamics in shaping cultural change. The book stands as an exemplary demonstration of his method—an ethnographic reading of history that foregrounds human experience and community over abstract narrative.

Los moriscos del Reino de Granada (The Moriscos of the Kingdom of Granada, 1957)

This work delves into the history and fate of the Moriscos, the Muslim converts to Christianity who were expelled from Spain in the early seventeenth century. Combining meticulous historical research with anthropological insight, Caro Baroja analyses the cultural assimilation, resistance, and eventual persecution of this community. He situates their story within a broader reflection on intolerance, identity, and the politics of difference. The book is both a historical study and a meditation on cultural coexistence—a topic that resonated deeply in mid-twentieth-century Spain.

Los Baroja (The Baroja Family, 1972)

In this partly autobiographical and partly historical account, Caro Baroja explores the legacy of his own family, one of Spain’s most remarkable intellectual dynasties. He situates his relatives—particularly his uncle Pío and his mother Carmen—within the cultural life of early twentieth-century Spain, linking their creative pursuits to broader social and political transformations. The work reflects not only familial pride but also his characteristic anthropological curiosity, as he treats his own lineage as a microcosm of the Spanish intelligentsia and its moral dilemmas.

El carnaval (Carnival, 1965)

This study of carnival traditions across Spain and Europe examines the role of festive rituals in mediating social tensions and renewing communal bonds. Caro Baroja traces the historical roots of carnival to pagan and medieval customs, exploring its transformation over the centuries. He interprets carnival as both a space of inversion—where hierarchies are temporarily subverted—and a mechanism of social continuity. His analysis bridges anthropology, folklore, and psychology, illustrating how ritual disorder can paradoxically sustain social order.

Ensayo sobre la literatura de cordel (Essay on Chapbook Literature, 1969)

In this investigation of popular printed literature—often cheap pamphlets and ballads distributed to rural audiences—Caro Baroja highlights how folk culture and mass communication intersected in pre-modern Spain. He demonstrates that these texts played a crucial role in shaping public consciousness, moral imagination, and local identities. The book is also an early study of what would later be called popular culture, showing Caro Baroja’s attentiveness to everyday forms of creativity and storytelling that lay outside elite literary traditions.

La cara, espejo del alma (The Face, Mirror of the Soul, 1986)

One of his later and more reflective works, this book explores the human face as a cultural, symbolic, and psychological object. Caro Baroja examines physiognomy, portraiture, and expression through literature, art, and anthropology, revealing how societies have interpreted the face as a window into character and morality. The text exemplifies his humanistic breadth and his ability to move fluidly between disciplines, linking folklore, philosophy, and visual culture in a meditation on identity and perception.

3) Main Themes

The Interplay between Tradition and Modernity

A central theme throughout Julio Caro Baroja’s oeuvre is the tension between traditional ways of life and the forces of modernity. He observed that rapid industrialisation, centralisation, and urbanisation in twentieth-century Spain often led to the erosion of local customs and collective memory. In works such as Los pueblos de España, he highlighted how each community’s identity was deeply rooted in centuries-old practices, beliefs, and linguistic expressions. Caro Baroja saw the modern impulse to homogenise culture as a form of loss—a forgetting of the complex social ecosystems that had sustained rural life. For him, studying folklore and rituals was not nostalgia, but a means to understand how societies maintain coherence amid change.

At the same time, Caro Baroja avoided romanticising the past. His analyses of festivals, superstition, and everyday practices revealed how tradition itself could both preserve and constrain communities. He recognised that even as traditional forms waned, they left behind traces that continued to shape the imagination of modern Spaniards. His nuanced approach presented tradition not as static, but as a dynamic process of adaptation. Through this perspective, Caro Baroja illuminated the coexistence of ancient and contemporary sensibilities in Spanish life, showing how cultural evolution was never purely linear but cyclical and layered.

The Study of Witchcraft and Superstition

Witchcraft and superstition occupied a significant place in Caro Baroja’s thought, serving as lenses through which he examined the deeper structures of belief and fear in European societies. In Las brujas y su mundo, he approached witchcraft not as a marginal curiosity but as a complex social phenomenon born of historical conditions. By analysing inquisitorial records, oral traditions, and theological texts, he revealed that accusations of witchcraft often reflected social tensions—between men and women, elites and peasants, orthodoxy and dissent. His work challenged earlier depictions of witchcraft as irrational folklore, instead framing it as a product of human anxiety, persecution, and the need for communal scapegoats.

Caro Baroja’s interpretation of superstition was profoundly anthropological. He saw in it a logic that, while different from scientific reasoning, expressed humanity’s enduring attempt to explain uncertainty and misfortune. By connecting myth and ritual to psychological and sociological dimensions, he helped elevate the study of popular belief to a serious scholarly pursuit. His writings demonstrated that superstition could serve as a historical archive of collective emotion—fear, hope, and imagination—transmitted across generations.

The Diversity of Spanish Identity

Another major theme in Caro Baroja’s scholarship was the pluralism of Spanish identity. He rejected the idea of a single, uniform Spanish culture, arguing instead that Spain was a mosaic of regional and linguistic communities. His ethnographic studies of the Basque Country, Navarre, and Andalusia demonstrated how geography, history, and local tradition interacted to produce distinctive cultural patterns. In Los pueblos de España, he portrayed Spain as a land of multiple civilisations layered upon one another—Celtic, Roman, Arab, Christian—each leaving its imprint on the social fabric.

This vision of Spain’s diversity was not only descriptive but also political. Writing during the Franco regime, which sought to suppress regional identities, Caro Baroja’s work quietly affirmed the legitimacy of cultural difference. His insistence on pluralism reflected a humanistic conviction that unity could coexist with diversity. By documenting dialects, customs, and beliefs that were at risk of extinction, he contributed to the preservation of Spain’s cultural heritage and laid the groundwork for future anthropological and linguistic studies in the Iberian context.

The Relationship between History and Anthropology

Caro Baroja’s intellectual method was characterised by a deep fusion of historical and anthropological inquiry. He believed that to understand a culture, one must examine its historical development, and conversely, that history could only be meaningful when interpreted through lived experience. His works—ranging from La hora navarra del XVIII to El carnaval—demonstrate how historical structures manifest in everyday practices, symbols, and rituals. He used anthropological observation to fill the gaps left by traditional historiography, especially when dealing with marginalised or forgotten populations.

This interdisciplinary approach allowed Caro Baroja to transcend the academic boundaries of his time. He treated historical archives and folklore with equal seriousness, reading both as expressions of collective meaning. By doing so, he anticipated later developments in cultural history and historical anthropology. His methodology emphasised that culture is both product and producer of history—a continuum in which social structures, imagination, and material conditions interact. Through this lens, he helped redefine what it meant to study the past, moving away from political events toward the rhythms of everyday life.

Ritual, Festival, and Social Order

Festive traditions and collective rituals were another enduring concern for Caro Baroja, who regarded them as mirrors of societal structure. In El carnaval and related studies, he explored how festivals served as both an expression of joy and a mechanism of control. The inversion of roles during carnival—peasants mocking nobles, men dressing as women, authority figures being parodied—revealed to him a profound truth about social cohesion: that order is often maintained through controlled disorder. These ritualised reversals allowed communities to release tension and reaffirm unity through symbolic transgression.

Caro Baroja’s reading of ritual drew on anthropology, sociology, and psychology. He interpreted communal celebrations as enactments of shared values, moral codes, and historical memory. In his view, rituals condensed the contradictions of social life, providing both continuity and catharsis. His exploration of the carnivalesque prefigured later cultural theories by scholars such as Mikhail Bakhtin, who similarly saw laughter and play as subversive yet essential to human society. Caro Baroja’s analyses demonstrated his acute understanding of how performance and symbolism underpin the moral and emotional fabric of communities.

Cultural Memory and the Persistence of the Past

A recurrent motif in Caro Baroja’s writings is the idea that the past never fully disappears but lingers within contemporary forms. Whether studying witchcraft, folklore, or rural architecture, he traced the survival of ancient beliefs beneath modern practices. He was fascinated by the concept of “cultural residues”—customs, sayings, or gestures that endure even after their original context is forgotten. In this sense, his work resonated with the historical anthropology of memory, suggesting that culture is a palimpsest continuously rewritten by each generation.

For Caro Baroja, memory was not simply individual but collective, a living archive that shapes identity and worldview. He saw oral traditions and vernacular rituals as repositories of historical consciousness, allowing ordinary people to participate in the making of history. By recovering these subtle continuities, he sought to reveal how even seemingly marginal aspects of life—superstitions, proverbs, festivals—encode profound historical experience. His sensitivity to cultural memory reflects his broader humanistic vision: that every society, however humble, carries within it the echoes of its past, which must be listened to with care and respect.

4) Baroja as an Anthropologist

Julio Caro Baroja stands as one of the most significant figures in twentieth-century Spanish anthropology, a scholar who blended erudition with empathy to illuminate the intricate textures of everyday life. His anthropological vision was both deeply rooted in the specificities of Spanish culture and broadly comparative, engaging with European intellectual traditions from Frazer to Lévi-Strauss. Unlike many anthropologists of his time, who sought to study distant or “exotic” societies, Caro Baroja turned his gaze inward—to the villages, customs, and oral traditions of his own country. This inward focus was not provincialism but a deliberate methodological choice: he believed that Spain itself contained a microcosm of human diversity, a living archive of Europe’s ancient past preserved through its regional cultures. His work thus redefined anthropology as a means of understanding not just others, but ourselves.

Caro Baroja’s fieldwork, particularly in the Basque Country and Navarre, exemplified his distinctive anthropological approach. He combined direct observation with historical research, linguistic analysis, and a sensitivity to local psychology. His ethnographic studies of festivals, witchcraft, and kinship were informed by long-term engagement with communities, many of whom he came to know personally. Rather than extracting data, he listened to stories, participated in rituals, and reconstructed the meaning of symbols in their social context. This participatory method reflected his belief that anthropology was as much an art as a science—a dialogue between observer and observed, grounded in respect for cultural difference.

One of Caro Baroja’s most enduring contributions was his emphasis on the interconnectedness of anthropology and history. He rejected the notion that anthropology should confine itself to the study of “primitive” societies, arguing instead that all cultures, including modern ones, possess anthropological depth. In works such as La hora navarra del XVIII and El carnaval, he demonstrated that historical documents could serve as ethnographic evidence and that rituals and customs could be read as living history. This integrative vision made him a precursor of what would later be termed “historical anthropology.” By blurring disciplinary boundaries, Caro Baroja showed that cultural patterns are not timeless structures but products of specific historical trajectories.

Caro Baroja’s anthropological writings were also distinguished by their humanistic sensibility. He approached the communities he studied not as objects of analysis but as bearers of wisdom, imagination, and dignity. His portrayals of rural life were marked by empathy and subtlety, avoiding both idealisation and condescension. He was particularly attentive to the ways in which ordinary people make sense of suffering, uncertainty, and change. In his studies of witchcraft, for example, he treated accused women not as deluded or wicked but as victims of fear and repression, and at times as figures of resistance within oppressive social structures. This ethical dimension of his work continues to inspire anthropologists concerned with representation and power.

Language, for Caro Baroja, was another vital component of anthropology. Fluent in Basque and deeply knowledgeable about Spain’s linguistic diversity, he understood that language embodies a community’s worldview. His studies often examined proverbs, idioms, and oral storytelling as expressions of collective psychology. He viewed the disappearance of dialects as a profound cultural loss, akin to the extinction of species. By documenting vernacular speech, he sought to preserve not merely words but the modes of thought they carried. His linguistic sensitivity anticipated later trends in symbolic and interpretive anthropology, which recognised language as the key to understanding cultural meaning.

Caro Baroja’s methodology was eclectic yet rigorously grounded. He drew from sociology, psychology, folklore, and philology, but always with a unifying vision: to capture the totality of human experience. He resisted theoretical dogmatism, preferring to let empirical detail guide interpretation. This intellectual independence occasionally placed him at odds with more systematised schools of anthropology, yet it gave his work a timeless quality. His refusal to separate the rational from the emotional, or the scholarly from the poetic, made his anthropology not merely descriptive but existential—a reflection on what it means to be human in a world of change and continuity.

Internationally, Caro Baroja’s anthropological legacy was recognised for its originality and depth. Though he worked largely within Spain, his insights resonated with scholars across Europe and the Americas who sought to reconnect anthropology with history and ethics. His insistence on understanding culture through lived experience rather than abstract models anticipated later critiques of structuralism and positivism. Today, his writings are seen as foundational to Iberian anthropology and as models for interdisciplinary cultural analysis.

Julio Caro Baroja’s anthropology was an act of preservation, interpretation, and profound human sympathy. He used ethnography to rescue the fragments of a vanishing world, but also to show that beneath the surface of custom and ritual lies the universal drama of human existence. His work continues to remind scholars that the study of culture is inseparable from the study of time, memory, and moral imagination. Through his eyes, anthropology became not only a science of society but also a philosophy of humanity itself.

5) His Legacy

Julio Caro Baroja’s legacy endures as one of the most profound and multifaceted in the history of Spanish intellectual life. His work transformed anthropology and ethnography in Spain from marginal pursuits into rigorous, humanistic disciplines capable of interpreting the country’s complex cultural fabric. Before Caro Baroja, much of Spanish folklore and local tradition had been treated as quaint curiosities; through his meticulous research and interpretive depth, he elevated them to the status of serious cultural knowledge. He demonstrated that Spain’s diversity—linguistic, regional, and historical—was not an obstacle to understanding its identity but the very essence of it. This perspective helped redefine how Spaniards saw themselves, fostering a renewed respect for regional heritage and collective memory.

Within the broader field of anthropology, Caro Baroja’s influence lies in his unique synthesis of history and ethnography. He pioneered what would later be known as “historical anthropology,” decades before it became a mainstream academic current. By treating archival documents, oral traditions, and social customs as equally valid sources of evidence, he blurred the artificial boundary between the past and the present. His approach encouraged later scholars to view culture as a dynamic process, shaped by centuries of transformation and adaptation. This methodological innovation resonated beyond Spain, influencing anthropologists and historians across Europe who sought to integrate human experience with historical consciousness.

Caro Baroja’s writings also left a deep imprint on the preservation of cultural heritage. At a time when industrialisation and centralisation were eroding traditional lifeways, his studies captured the fragile details of language, ritual, and belief that might otherwise have been lost. His fieldwork in the Basque Country and Navarre, for instance, not only contributed to scholarship but also served as a cultural safeguard. His careful documentation of dialects, proverbs, and oral narratives provided future generations with a repository of identity and continuity. Many of his ethnographic insights have since been incorporated into museum collections, educational curricula, and regional heritage initiatives.

His influence extended far beyond anthropology into literature, sociology, and cultural history. Writers and intellectuals admired his prose for its clarity and sensitivity, while academics praised his interdisciplinary curiosity. His reflections on superstition, ritual, and social order inspired later thinkers interested in symbolic anthropology and the anthropology of religion. In many ways, Caro Baroja served as a bridge between generations—linking the humanistic traditions of early twentieth-century Spain with the emerging social sciences of the post-war era. His legacy thus represents not only a body of work but also an intellectual ethos grounded in respect for complexity and difference.

In Spain, his contributions are commemorated through numerous awards, academic institutions, and cultural programmes. The Julio Caro Baroja Foundation, established after his death, continues to promote research in anthropology, folklore, and history, reflecting his enduring commitment to interdisciplinary study. His ideas also influence contemporary debates about cultural identity and diversity within Spain, especially in discussions surrounding regional autonomy and linguistic preservation. By championing pluralism and local identity during politically restrictive times, Caro Baroja became a quiet yet powerful advocate for cultural freedom.

Internationally, his name is often mentioned alongside other European anthropologists who sought to integrate ethnography with historical and philosophical reflection. Yet, unlike many of his peers, Caro Baroja never distanced himself from his own culture; his intellectual project remained profoundly local while achieving universal resonance. His writings on witchcraft, festivals, and superstition continue to be cited in comparative studies across anthropology, history, and religious studies. Scholars still turn to him as a model of how to combine rigorous analysis with poetic understanding—a rare fusion that grants his work enduring vitality.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of Caro Baroja’s legacy is the moral and emotional depth of his scholarship. He taught that the study of human beings requires empathy as well as intellect, and that understanding culture means recognising the dignity of those who live within it. His commitment to documenting marginal voices and forgotten traditions made anthropology an act of preservation as much as interpretation. In doing so, he left behind more than a library of books; he left a vision of culture as a living, breathing entity, sustained by memory and imagination.

Julio Caro Baroja’s intellectual journey concluded in 1995, but his influence continues to shape Spanish and European thought. His work remains a reminder that culture, in all its contradictions, is both the inheritance and the creation of ordinary people. Through his eyes, anthropology became not just the study of customs but a profound meditation on what it means to belong—to a place, a history, and a shared human story. His legacy thus stands as a testament to the enduring power of curiosity, humility, and the search for meaning within the everyday.