Jean Rouch

1) His Biography

Jean Rouch was born on 31 May 1917 in Paris, France, into a family that valued both the arts and sciences. Initially, his academic interests leaned toward engineering, and he pursued studies at the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, one of France’s most prestigious engineering schools. However, the Second World War profoundly altered the course of his life. During his service as a civil engineer in French West Africa, he was confronted with the complex social and cultural worlds of African societies, sparking a deep curiosity that would eventually lead him away from engineering and towards anthropology and filmmaking. His early encounters with African communities along the Niger River laid the foundation for his lifelong fascination with ethnography and cross-cultural representation.

After the war, Rouch began formal studies in anthropology under the mentorship of Marcel Griaule, one of the leading French anthropologists of the time. Griaule’s focus on fieldwork and symbolic interpretation greatly influenced Rouch, who embraced the immersive approach of living among and learning from the people he studied. Rouch conducted extensive fieldwork among the Songhai, the Dogon, and the Sorko peoples, recording their rituals, myths, and daily lives. His doctoral thesis, completed in the 1950s, focused on spirit possession and religious practices, but his use of film as a research tool distinguished him from his contemporaries and began to establish his reputation as a pioneer in visual anthropology.

By the late 1940s, Rouch had started using a camera to document his fieldwork, producing some of his first films such as Au pays des mages noirs (1947). His use of film was initially intended as an ethnographic record, but it soon evolved into an art form that blurred the line between scientific documentation and creative storytelling. He realised that film could not only capture behaviour and ritual but also reveal emotional and psychological truths inaccessible through traditional ethnographic writing. This dual commitment to anthropology and cinema would become the hallmark of his career, defining his contribution to both disciplines.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Rouch became a central figure in the development of cinéma vérité—a style of documentary filmmaking that sought to depict reality with minimal interference. Working with lightweight cameras and synchronised sound equipment, he emphasised spontaneity, participation, and reflexivity in his films. His collaborations with African actors and storytellers, most notably Oumarou Ganda, produced some of his most acclaimed works, such as Moi, un Noir (1958) and La Pyramide humaine (1961). These films broke new ground in ethnographic cinema by giving African subjects the space to interpret and narrate their own experiences.

Rouch’s anthropological work was as innovative as his filmmaking. He became known for his concept of “shared anthropology,” which proposed that ethnographic research should be a collaborative process between the anthropologist and the subjects. This approach rejected the traditional hierarchical model of Western observation and instead encouraged dialogue and co-creation. His methods were both celebrated and controversial, as they challenged established academic conventions and raised questions about the boundaries between observer and participant. Rouch saw anthropology as an ethical and imaginative exchange, where truth emerged through interaction rather than objectivity.

In addition to his films, Rouch held significant academic and institutional roles. He served as a researcher at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and taught at various universities, influencing generations of anthropologists and filmmakers. His lectures and writings explored the intersections of ritual, performance, and cinematic representation, continually pushing the boundaries of how culture could be studied and portrayed. He was also instrumental in establishing institutions for film and ethnography in Africa, including his work with the Nigerian Film Unit, which nurtured local cinematic talent.

Over the course of his career, Jean Rouch directed more than one hundred films and became one of the most respected voices in both anthropology and world cinema. His work inspired the French New Wave and influenced filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. Despite occasional criticism regarding his portrayal of African subjects, his commitment to dialogue and collaboration made him a bridge between cultures at a time when decolonisation was transforming global relations. His legacy remains that of a thinker who expanded the possibilities of both ethnography and film.

Jean Rouch died tragically in a car accident in Niger on 18 February 2004, a country that had become his second home. His death marked the end of a career that spanned over half a century of artistic and intellectual experimentation. Yet his influence continues to resonate through contemporary anthropology and documentary filmmaking, where his belief in the shared creation of knowledge still challenges and inspires. Rouch’s life embodied the very principle he championed: that understanding others begins not with detachment, but with genuine human connection.

2) Main Works

Au pays des mages noirs (1947)

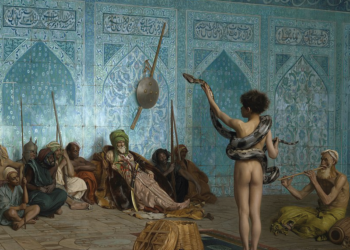

Jean Rouch’s first ethnographic film, Au pays des mages noirs (“In the Land of the Black Magicians”), documents a series of rituals and ceremonies performed by the Songhai and Sorko peoples of Niger. Shot during his early fieldwork as a young engineer-turned-anthropologist, the film reflects his fascination with spirit possession and traditional African cosmologies. Although the film was initially intended as a scientific record for academic audiences, it also reveals Rouch’s growing awareness of the expressive and narrative potential of film. Despite later criticisms for its exoticised tone, it laid the groundwork for Rouch’s lifelong commitment to capturing African realities through direct observation and visual storytelling.

Les Maîtres fous (1955)

One of Rouch’s most famous and controversial works, Les Maîtres fous (“The Mad Masters”) depicts the Hauka movement in Ghana, in which participants perform possession rituals that mimic the colonial hierarchy. The film portrays Africans taking on the roles of European officials—governors, engineers, and soldiers—through ritual trance, offering a striking commentary on colonial domination and resistance. While some Western critics misinterpreted the film as a display of savagery, Rouch intended it as a complex exploration of catharsis, mimicry, and power. Les Maîtres fous remains a foundational text in visual anthropology and postcolonial theory, illustrating how ritual can function as a form of social and psychological resilience under colonial rule.

Moi, un Noir (1958)

A groundbreaking work of ethnographic fiction, Moi, un Noir (“I, a Negro”) follows the lives of young Nigerien immigrants working in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. The film blends documentary observation with fictional narration, as the protagonist—played by Oumarou Ganda—portrays himself through an alter ego named Edward G. Robinson. Rouch’s innovative use of improvisation, voice-over commentary, and collaborative storytelling blurred the lines between filmmaker and subject, giving voice to African perspectives on modernity, migration, and identity. The film received the Prix Louis-Delluc in 1958 and profoundly influenced the emergence of cinéma vérité and the French New Wave through its intimate, participatory style.

La Pyramide humaine (1961)

In La Pyramide humaine (“The Human Pyramid”), Rouch turns his camera on the dynamics of race, youth, and love in an Abidjan high school. The film brings together African and European students who act out a semi-fictional story of interracial friendship and romance, revealing the social tensions and hopes of a postcolonial generation. Rather than directing them in a conventional sense, Rouch invited the students to improvise and shape the narrative themselves. The result is a film that captures the spontaneity and uncertainty of real human relationships, reflecting Rouch’s belief in cinema as a shared creative act. It stands as one of his most experimental and humane works.

Chronique d’un été (1961)

Co-directed with sociologist Edgar Morin, Chronique d’un été (“Chronicle of a Summer”) is a landmark in cinéma vérité. Filmed in Paris during the summer of 1960, it explores the daily lives, opinions, and emotions of ordinary Parisians through candid interviews and unscripted encounters. The film famously opens with the question, “Are you happy?”—an inquiry that reveals both personal and political dimensions of post-war French society. By involving participants in the editing and reflection process, Rouch and Morin introduced the notion of reflexivity in documentary filmmaking. Chronique d’un été remains a key example of Rouch’s philosophy of “shared anthropology” and is widely regarded as one of the most influential documentaries ever made.

Jaguar (1967)

Although filmed in the 1950s, Jaguar was edited and released in 1967, featuring Oumarou Ganda, Lam Ibrahim Dia, and Illo Gaoudel as three young Nigerien men travelling to the Gold Coast in search of work. The film juxtaposes observational footage with humorous and reflective voice-over commentary recorded later by the participants themselves. This technique allows the subjects to reinterpret their own journey, transforming what began as ethnographic documentation into a collaborative, self-reflexive narrative. Jaguar exemplifies Rouch’s belief that ethnography could be both a scientific and artistic partnership between filmmaker and subject, and it remains one of his most beloved films for its warmth, humour, and humanity.

Petit à petit (1971)

A semi-sequel to Jaguar, Petit à petit (“Little by Little”) follows African entrepreneurs who travel to Paris to study French society with the aim of modernising their own country. Through a humorous and ironic reversal of the ethnographic gaze, the film critiques Western modernity and the assumptions underlying anthropological observation itself. As the protagonists interview Parisians and observe their customs, they expose the absurdities and contradictions of French social life. Petit à petit thus stands as both a playful satire and a profound commentary on cultural difference, colonialism, and reciprocity in human understanding.

Cocorico! Monsieur Poulet (1974)

Made in collaboration with Damouré Zika and Lam Ibrahim Dia, Cocorico! Monsieur Poulet (“Cock-a-doodle-doo! Mr Chicken”) is an improvised road movie set in Niger that follows three friends on a journey to sell chickens. Combining fiction, documentary, and comedy, the film captures the unpredictability of everyday life in rural West Africa. The trio’s adventures—marked by car troubles, bargaining, and encounters with locals—reveal themes of friendship, ingenuity, and resilience. Rouch’s playful narrative style and the film’s collaborative spirit showcase his enduring dedication to storytelling as a shared cultural act rather than a unilateral depiction. It remains one of his most endearing and widely celebrated works.

3) Main Themes

The Fusion of Anthropology and Cinema

One of the central themes in Jean Rouch’s oeuvre is the merging of anthropology and cinema into a unified mode of inquiry. For Rouch, film was not simply a recording device but a means of thinking anthropologically—a tool that could capture movement, gesture, and emotion in ways that written ethnography could not. Through his use of film, he sought to reveal the lived experience of cultural practices, transforming anthropology from an exercise in detached observation into an immersive and participatory art. His films demonstrated that visual storytelling could both document and interpret culture, providing an empathetic lens through which to understand others.

This fusion gave rise to what Rouch termed cine-anthropology, a form of ethnographic filmmaking grounded in collaboration, improvisation, and reflexivity. Rather than presenting film as objective truth, he acknowledged its performative and interpretative nature, showing that every image is a product of interaction between filmmaker and subject. His works, particularly Les Maîtres fous and Moi, un Noir, exemplify how cinema can simultaneously convey scientific insight and emotional truth. In doing so, Rouch redefined anthropology as an art of encounter—where the act of filming itself became a moment of cross-cultural exchange and understanding.

Shared Anthropology and Collaboration

A defining philosophical and methodological innovation in Rouch’s work was the concept of shared anthropology. This approach rejected the colonial hierarchies implicit in traditional ethnographic research, advocating instead for a form of collaboration in which subjects became co-authors of their representation. Rouch believed that the anthropologist’s role was not to interpret others from a position of authority, but to engage in dialogue and create meaning together. His films were therefore conceived as collective creations—part research, part friendship, and part performance.

This principle of sharing was evident in his long-standing collaborations with African actors such as Oumarou Ganda and Damouré Zika, who contributed to both the narratives and the commentary in films like Jaguar and Petit à petit. By allowing his participants to narrate and reinterpret their own experiences, Rouch dismantled the boundaries between observer and observed. The result was a form of anthropology that was as ethical as it was aesthetic—one that embraced subjectivity, reciprocity, and mutual respect. Shared anthropology became Rouch’s enduring legacy, influencing both documentary practice and postcolonial thought.

Reflexivity and the Role of the Filmmaker

Rouch’s work is characterised by a profound awareness of the filmmaker’s presence and influence within the ethnographic encounter. He argued that the act of filming inevitably transforms the situation being recorded, and therefore, reflexivity—the acknowledgment of the camera’s effect—was essential to honest representation. His films often foregrounded the process of filmmaking itself, allowing subjects to comment on their portrayal and viewers to witness the dynamics of interaction. This reflexive stance marked a departure from earlier ethnographic traditions that sought to conceal the filmmaker’s role in pursuit of scientific neutrality.

In Chronique d’un été, co-directed with Edgar Morin, this reflexivity becomes the film’s very subject. The participants are invited to view and discuss their own footage, engaging in an open conversation about the truthfulness of their representations. For Rouch, such transparency was not a weakness but a form of integrity. It highlighted the collaborative nature of truth-making in anthropology and cinema alike. Through reflexivity, Rouch transformed film into a mirror of mutual discovery, where self and other continually reflect and redefine one another.

Representation, Power, and Decolonisation

Another central theme in Rouch’s work is his engagement with the politics of representation, particularly in relation to colonialism and postcolonial identity. Working in Africa during and after the colonial period, he was acutely aware of the power dynamics inherent in the act of filming. His films, especially Les Maîtres fous, confronted the legacies of colonial domination and the complexities of cultural mimicry. By depicting rituals of possession that re-enacted the authority of colonial figures, Rouch exposed how colonised subjects internalised and subverted power through symbolic performance.

Yet Rouch’s own position as a white European documenting African societies was a source of ongoing tension and debate. Critics accused him at times of perpetuating exoticism, while supporters saw him as a pioneer of cultural empathy and collaboration. Rouch responded to such critiques not by denying his positionality but by embracing transparency and partnership. His works illustrate how decolonisation could also occur within anthropology itself—through dialogue, creative reciprocity, and the recognition of shared humanity. Thus, Rouch’s cinema became not just a record of postcolonial Africa but an experiment in ethical coexistence.

Improvisation and Spontaneity

Improvisation occupies a vital place in Rouch’s artistic and anthropological vision. He believed that reality could best be understood not through rigid scripting or control, but through openness to the unpredictable flow of human life. His camera functioned as a catalyst rather than a recorder, inviting spontaneity from those in front of it. This method reflected his conviction that authenticity lies in interaction—when filmmaker and subject co-create meaning in the moment. Films like Moi, un Noir and Cocorico! Monsieur Poulet exemplify this approach, where dialogue, narrative, and performance emerge organically from lived situations rather than prearranged plots.

This reliance on improvisation also linked Rouch’s cinema to the aesthetic revolutions of the French New Wave. His mobile camera work, use of non-professional actors, and unscripted dialogue influenced filmmakers such as Godard and Truffaut, who adopted similar techniques to capture the immediacy of modern life. For Rouch, improvisation was not merely a style but a philosophy—an acknowledgment that culture, like film, is a dynamic process shaped by encounter and change. It embodied his belief that truth is not static but continually negotiated through creative engagement.

The Anthropology of Everyday Life

Rouch’s films often turned their gaze away from grand narratives and formal rituals to focus on the texture of everyday existence. He viewed daily life—its gestures, humour, and struggles—as a rich site of cultural meaning. This emphasis on the ordinary was revolutionary for ethnographic cinema, which had traditionally prioritised ceremonial or exotic spectacles. In films such as Jaguar and Chronique d’un été, Rouch captured the rhythms of labour, conversation, and leisure, treating them with the same dignity and interpretative depth as sacred rituals.

By portraying ordinary people as active agents of cultural creation, Rouch dissolved the boundaries between the extraordinary and the mundane. His anthropological lens revealed that meaning and myth could be found in the smallest interactions, whether in a market, a city street, or a casual conversation. This focus on everyday life humanised his subjects and expanded the scope of anthropology itself, suggesting that understanding humanity begins with attending to the details of how people live, speak, and imagine their worlds.

The Blurring of Documentary and Fiction

A hallmark of Rouch’s filmmaking is his refusal to draw a strict line between documentary and fiction. He believed that both modes could reveal truth, provided they were rooted in genuine human experience. His hybrid films, such as Moi, un Noir and La Pyramide humaine, blend real events with invented dialogue and improvised storytelling, allowing participants to express their own interpretations of reality. This fusion created a new cinematic language—part ethnography, part autobiography, part social reflection.

For Rouch, fiction was not a distortion of truth but a means of reaching it more deeply. When subjects re-enacted their lives or invented new versions of themselves on camera, they exposed the emotions, aspirations, and contradictions that structured their existence. This “ethnofiction” approach became one of Rouch’s most influential contributions, inspiring filmmakers across the world to explore the boundaries between observation and imagination. Through this blending of genres, Rouch revealed that all representation—whether anthropological or cinematic—is ultimately an act of creative interpretation.

4) Rouch as an Anthropologist

Jean Rouch’s identity as an anthropologist is inseparable from his innovative use of film as a research tool. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not confine himself to textual analysis or the production of dry ethnographic monographs. Instead, he embraced visual media as a way of capturing the nuances of human behaviour, social rituals, and cultural expression. Rouch believed that anthropology should be an immersive experience, where the researcher engages directly with the communities studied rather than observing from a detached standpoint. His early work among the Songhai, Sorko, and Dogon peoples of Niger provided him with the foundation for this approach, as he lived among them, learned their languages, and participated in daily life while simultaneously documenting their customs on film.

Central to Rouch’s anthropological philosophy was the principle of shared anthropology. He rejected the traditional hierarchical model in which the anthropologist interpreted the “other” for an external audience. Instead, he encouraged collaboration, dialogue, and co-authorship, allowing the subjects of his films to narrate and interpret their own lives. In practice, this meant that individuals featured in his films were not passive objects of study but active participants who shaped both narrative and presentation. This methodological shift challenged conventional notions of objectivity in ethnography and positioned Rouch at the forefront of a more participatory, ethical form of anthropology.

Rouch also expanded the anthropological imagination by embracing the concept of ethnofiction—the blending of documentary observation with fictionalised storytelling. In works like Moi, un Noir and Jaguar, participants play themselves in staged or partially improvised scenarios, enabling anthropological truths to emerge through performance and reflection. By combining lived experience with creative narrative, Rouch demonstrated that culture is not merely a set of observable behaviours but a dynamic, interpretative process. This approach allowed him to explore subjective experience, emotions, and aspirations—dimensions often overlooked in traditional ethnography.

Another defining feature of Rouch’s anthropological work was reflexivity. He was acutely aware that the presence of the camera, and of himself as a European filmmaker, inevitably influenced the behaviours and interpretations of his subjects. Rather than attempting to conceal this influence, Rouch made it an explicit element of his work. In Chronique d’un été, co-directed with Edgar Morin, he invited participants to reflect on their own filmed statements and to discuss the authenticity of their representations. This reflexive practice emphasised transparency and underscored the collaborative nature of anthropological knowledge.

Rouch’s anthropological contributions also extended to methodological innovation. He championed the use of lightweight cameras and synchronised sound equipment, allowing for mobile and unobtrusive recording in field conditions. This technical adaptability enabled him to capture spontaneous events, rituals, and interactions that traditional observational methods might have missed. His work influenced subsequent generations of visual anthropologists, demonstrating that rigorous scholarship could coexist with artistic sensibility and narrative experimentation.

Ethnography in Rouch’s view was not only about documenting culture but also about fostering understanding across social and cultural divides. His films reveal the ways in which communities negotiate identity, memory, and power, and they highlight the agency of people who are often marginalised or misrepresented. By foregrounding local voices and lived experience, Rouch’s anthropology challenged colonial and Eurocentric perspectives, advocating for a more equitable and dialogical approach to knowledge production.

5) His Legacy

Jean Rouch’s legacy is both vast and multifaceted, encompassing anthropology, cinema, and the broader fields of cultural theory. Perhaps his most enduring contribution is the establishment of visual anthropology as a legitimate and innovative discipline. By demonstrating that film could serve as both a research tool and a medium for storytelling, Rouch expanded the methodological horizons of anthropology. He showed that understanding human cultures required not only textual analysis but also attention to gestures, speech, ritual, and performance—elements that could be captured most vividly on film. This integration of observation, creativity, and empathy has influenced generations of anthropologists, filmmakers, and ethnographers worldwide.

Rouch’s commitment to shared anthropology continues to resonate as a model of ethical research. His insistence that subjects participate actively in the creation and interpretation of their representation challenged hierarchical notions of authorship and authority. Today, collaborative and participatory approaches in anthropology, documentary filmmaking, and ethnography owe much to Rouch’s pioneering vision. By giving agency to those who had historically been studied rather than consulted, he reframed the relationship between researcher and subject as a dialogue rather than a monologue, fostering a more inclusive and human-centred practice.

In cinema, Rouch’s influence is equally significant. He is widely recognised as a founder of cinéma vérité and a major inspiration for the French New Wave. Filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Chris Marker drew on his innovative use of mobile cameras, natural lighting, and improvisational storytelling. His blend of documentary realism with creative narrative—what he termed ethnofiction—opened new possibilities for cinematic experimentation, influencing both narrative and non-fiction traditions. Beyond technique, Rouch demonstrated that cinema could be a tool for empathy, social critique, and intercultural understanding, rather than merely entertainment.

Rouch’s work also left an enduring imprint on postcolonial thought and the ethics of representation. By confronting the power dynamics inherent in documenting African societies during and after colonial rule, he challenged Western-centric perspectives and emphasised dialogue and reciprocity. Films such as Les Maîtres fous and Moi, un Noir continue to be studied for their nuanced approach to colonial history, cultural resistance, and the psychological and social effects of domination. His films encourage viewers to question how culture is represented and interpreted, a concern that remains central to contemporary debates in anthropology and media studies.

Beyond academia and cinema, Rouch’s influence is evident in his collaborations with African filmmakers and actors. He nurtured local talent, promoted cross-cultural creative projects, and helped establish infrastructures for filmmaking in West Africa. By doing so, he contributed to the growth of indigenous cinema and supported the development of African voices in global media. His collaborative ethos and mentorship modelled a way of working that prioritised respect, reciprocity, and cultural exchange, leaving a tangible impact on communities beyond the academic sphere.

Rouch’s approach to improvisation, playfulness, and the human dimension of research also forms a crucial part of his legacy. He demonstrated that serious scholarship need not be devoid of humour or creativity, and that the unpredictability of human behaviour could be embraced rather than controlled. This human-centred approach has influenced both qualitative social research and documentary practices, inspiring scholars and filmmakers to prioritise authenticity, spontaneity, and lived experience in their work.

Jean Rouch’s legacy endures in the philosophical and methodological questions he raised about knowledge, representation, and the role of the observer. His life’s work encourages us to recognise that understanding others requires humility, dialogue, and imaginative engagement. By bridging the domains of anthropology and cinema, Rouch created a model of scholarship that is at once rigorous, ethical, and profoundly human. His influence continues to shape how we study, represent, and connect with cultures across the world, ensuring that his vision of collaborative, empathetic inquiry remains alive in contemporary practice.