Françoise Héritier

1) Her Biography

Françoise Héritier was born on 15 November 1933 in Veauche, a small commune in central France. She grew up in a modest household that valued education and curiosity, qualities that would later define her intellectual pursuits. Her early education reflected the post-war French emphasis on rebuilding intellectual life, and from an early age she displayed a deep interest in the social sciences, particularly anthropology. Although her initial academic inclinations were towards history and philosophy, she was soon drawn to ethnology and the study of human societies, a field that was flourishing in France through the influence of figures such as Claude Lévi-Strauss.

Héritier pursued her higher education at the prestigious École normale supérieure de jeunes filles in Sèvres, an institution known for training some of the most prominent French intellectuals of the twentieth century. Under the intellectual climate of structuralism that dominated the 1950s and 1960s, she found her calling in anthropology. Her encounter with Lévi-Strauss was particularly formative; he became her mentor and a lifelong point of reference in her theoretical work. She would later succeed him at the Collège de France, becoming only the second woman ever to hold a chair at the institution, a remarkable achievement in a male-dominated academic environment.

Her first fieldwork took her to West Africa, particularly Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), where she studied the Samo and Mossi peoples. This field experience proved decisive for her intellectual development. It allowed her to combine empirical observation with structuralist analysis, focusing especially on kinship systems, gender relations, and symbolic classifications. Héritier’s meticulous approach and sensitivity to cultural detail distinguished her as an anthropologist capable of both rigorous theoretical reasoning and profound human insight. Her work demonstrated that kinship was not merely about genealogy but also about the distribution of roles, power, and meanings within society.

Throughout her career, Héritier’s research evolved towards questions of difference — particularly the biological and symbolic differences between the sexes. Building upon Lévi-Strauss’s insights, she introduced her own groundbreaking concept of the “differential valence of the sexes,” a theory that sought to explain why societies across the world consistently placed higher value on the male over the female. This idea became central to her intellectual legacy and established her as one of the foremost feminist thinkers within the anthropological tradition. She bridged the gap between structural anthropology and gender studies, enriching both fields with her original perspective.

Her appointment to the Collège de France in 1982 marked a turning point in her career, both symbolically and academically. Her chair, titled “Study of Comparative Societies,” gave her a platform to expand her analyses of kinship and gender beyond specific ethnographic cases, situating them within a universal framework of human thought. She also directed the Laboratory of Social Anthropology, continuing the institutional legacy of Lévi-Strauss while developing her own intellectual autonomy. Héritier’s presence at the Collège was also a victory for women in academia, and she became a role model for a new generation of female scholars in France and beyond.

Beyond her scholarly work, Héritier was also a public intellectual deeply engaged in contemporary social issues. She contributed to debates on feminism, bioethics, and equality, bringing anthropological insight into public discourse. Her writings, both academic and popular, often explored how the symbolic order of societies influences real-world inequalities. She participated in governmental and ethical committees, advocating for reproductive rights and against gender-based discrimination. Through her voice, anthropology was not confined to the study of distant societies but became a lens through which to understand modern power dynamics.

Her numerous publications — including Masculin/Féminin: La pensée de la différence and De la violence — received widespread acclaim for their clarity and intellectual depth. These works not only consolidated her theoretical contributions but also extended her ideas into questions of violence, reproduction, and the construction of identity. Her writing style combined analytical precision with philosophical reflection, making her accessible to both academic and general audiences. She thus stood at the intersection of science, philosophy, and activism, embodying a truly engaged form of scholarship.

Françoise Héritier passed away on 15 November 2017, coincidentally on her eighty-fourth birthday. Her death marked the end of an era in French anthropology but left behind a profound intellectual legacy. Her theories on gender, kinship, and the symbolic construction of difference continue to influence disciplines far beyond anthropology, from sociology and philosophy to feminist theory. As one of the few women to have reshaped the structuralist tradition from within, Héritier’s life and work remain a testament to intellectual courage, human curiosity, and the enduring power of critical thought.

2) Main Works

L’exercice de la parenté (1981)

This seminal work established Héritier’s reputation as one of the most innovative anthropologists of her generation. In L’exercice de la parenté, she revisited the foundations of kinship theory that had been laid by Claude Lévi-Strauss, offering both a continuation and a critique of structuralist analysis. Based on her fieldwork in West Africa, she explored how societies organise kinship through systems of alliance, filiation, and exchange. Héritier argued that kinship is not merely biological but profoundly symbolic, shaped by rules of reproduction and gendered relations. Her detailed ethnographic examples illuminated how kinship systems create and sustain social hierarchies, while also revealing the subtle dynamics of power embedded in familial and marital arrangements.

Masculin/Féminin: La pensée de la différence (1996)

This is arguably Héritier’s most influential work, in which she introduced her central concept of the valence différentielle des sexes — the “differential valence of the sexes.” Here, she examined how societies across history and geography have consistently assigned higher value to the masculine over the feminine, despite biological complementarity. Drawing upon anthropology, history, and psychology, Héritier proposed that this hierarchy stems from symbolic and reproductive logics deeply rooted in human culture. The book represents both a structural and feminist analysis, bridging anthropology and social critique. It positioned Héritier as one of the leading voices in feminist thought in France, offering a new framework for understanding the cultural construction of gender inequality.

De la violence (1996)

Published the same year as Masculin/Féminin, this book explored the anthropological and psychological dimensions of violence. Héritier argued that violence, far from being an aberration, is an inherent part of human societies, rooted in the ways individuals and groups seek to assert dominance and control. She investigated various forms of violence — physical, symbolic, and structural — and examined their connections to gender relations and social hierarchies. By linking the exercise of power to the reproduction of inequality, Héritier provided a compelling account of how violence is both a product and a mechanism of social organisation. Her reflections were not limited to so-called “primitive” societies but extended to modern contexts, demonstrating anthropology’s relevance to understanding contemporary issues.

Les deux sœurs et leur mère: Anthropologie de l’inceste (1994)

In this work, Héritier returned to one of anthropology’s most enduring taboos — incest. Drawing from extensive comparative data, she explored the social, biological, and symbolic reasons behind the prohibition of incest, focusing particularly on the role of women in the transmission of life. Her analysis revealed how prohibitions surrounding incest are linked to broader structures of gender and power, and how they underpin the reproduction of social order. By highlighting the recurring figure of the “two sisters and their mother,” she illustrated how cultural systems codify the flow of sexuality, reproduction, and inheritance. The book reaffirmed her position as a major theorist of kinship and human universals.

Les réflexes conditionnels: De l’anthropologie à la psychanalyse (2000)

Here, Héritier sought to build bridges between anthropology and psychoanalysis. She explored how cultural conditioning shapes individual reflexes, emotions, and desires, showing that many behaviours considered natural are in fact deeply social. The book offered an interdisciplinary dialogue on the human condition, connecting the study of kinship and symbols to unconscious processes. Héritier’s reflection on conditioned reflexes demonstrated her commitment to understanding the intersection between biological and cultural factors, an approach that characterised much of her later thought.

Masculin/Féminin II: Dissoudre la hiérarchie (2002)

In this sequel, Héritier deepened her analysis of gender and sought to envision ways of transcending the hierarchy between the sexes. She challenged the long-standing symbolic and cultural justifications for male dominance and argued for the possibility of dissolving this hierarchy through shifts in social values, education, and self-awareness. The book combined anthropological theory with ethical reflection, showing Héritier’s growing engagement with public and political questions. By advocating a transformation of the symbolic order itself, she called for a rethinking of gender relations at their most fundamental level — not merely in terms of equality of rights, but equality of recognition and value.

Le sel de la vie (2012)

A late and more personal work, Le sel de la vie departed from her strictly academic tone to reflect on the small, often overlooked pleasures that make human existence meaningful. Written in the form of a poetic letter to a friend, the book combined anthropology, philosophy, and autobiography. Héritier mused on the richness of everyday experiences — gestures, sensations, and encounters — as the true “salt of life.” The work was widely celebrated in France for its warmth and wisdom, revealing another side of Héritier: that of a thinker deeply attuned to the emotional and sensory dimensions of being human.

Le goût des mots (2013)

This book continued the introspective tone of Le sel de la vie, focusing on the pleasure and power of language. Héritier reflected on how words shape thought, emotion, and identity, linking linguistic creativity to the anthropological study of meaning. Drawing upon her lifelong fascination with symbols and communication, she explored how the act of naming and speaking structures human relationships and perceptions of reality. Le goût des mots showcased her literary sensibility and reaffirmed her belief that anthropology is ultimately a science of human expression — one that bridges the body, mind, and culture.

3) Main Themes

The Differential Valence of the Sexes

At the centre of Héritier’s thought lies the concept of the valence différentielle des sexes, the “differential valence of the sexes,” which refers to the universal tendency of societies to ascribe greater value to the male over the female. For Héritier, this asymmetry is neither natural nor inevitable, but a deeply ingrained symbolic construction that has shaped the organisation of human societies. She argued that from myths to social institutions, this hierarchy is perpetuated through a network of representations that link men to strength, culture, and transcendence, while women are associated with nature, fertility, and immanence. This framework allowed her to uncover the cultural and structural roots of gender inequality, transforming anthropology into a critical lens for understanding patriarchy.

Her analysis went beyond mere denunciation; she sought to understand why this pattern was so enduring across cultures. Héritier proposed that the symbolic privilege granted to men emerged from the biological fact that women alone have the capacity to give birth, a power that men have historically sought to control or appropriate. This fundamental difference, she argued, provoked an attempt by men to assert dominance through social and symbolic means. Her theory thus connects the biological to the cultural, suggesting that gender hierarchies originate in human interpretations of bodily difference rather than in the body itself.

Kinship and the Structure of Social Relations

Héritier’s early work focused on kinship systems, following in the intellectual tradition of Claude Lévi-Strauss but introducing significant innovations. She viewed kinship not simply as a system of biological descent or marital exchange, but as a symbolic network that governs the flow of life, inheritance, and alliance. Her ethnographic studies in Africa, particularly among the Samo and Mossi peoples, revealed the diversity and complexity of kinship rules across societies. She examined how relationships of blood, marriage, and filiation form the foundation of social organisation, determining both individual identity and communal cohesion.

However, Héritier’s key contribution was to show how kinship structures are intimately linked to ideas of gender and power. She demonstrated that kinship systems often encode social hierarchies, including the subordination of women and the regulation of their reproductive capacity. In her view, kinship is not a neutral mechanism but a cultural instrument through which societies reproduce inequality. By analysing incest prohibitions, lineage patterns, and the transmission of names and rights, she revealed how family structures mirror and sustain broader ideological orders.

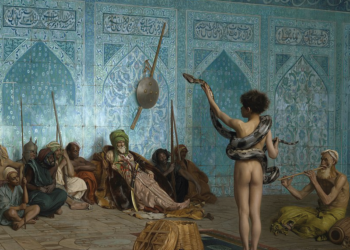

The Anthropology of Gender and Difference

Héritier was one of the first French anthropologists to systematically address the question of gender as a category of social thought. She treated gender not merely as a social role but as a symbolic and structural principle that shapes every aspect of human life. In her works Masculin/Féminin I and II, she explored how societies classify and interpret difference — biological, social, and moral — through the lens of gender. She argued that the binary opposition between male and female underlies many other systems of classification, including those that separate culture from nature, public from private, and sacred from profane.

Her approach to gender was profoundly structural yet politically engaged. She demonstrated that the apparent universality of male dominance was not an immutable fact but a cultural artefact, open to critique and transformation. By linking anthropological insight with feminist theory, Héritier offered a framework for challenging the symbolic hierarchies that sustain gender inequality. Her work inspired scholars and activists alike to rethink the cultural logic behind notions of masculinity and femininity, thus bridging academic anthropology and social change.

Incest and the Regulation of Desire

The theme of incest occupies a crucial place in Héritier’s analysis of kinship and social order. In Les deux sœurs et leur mère, she explored how the incest taboo — often regarded as a universal law — is culturally elaborated to regulate sexual and reproductive relations. For Héritier, the prohibition of incest was not merely a biological safeguard against inbreeding, as some theories suggest, but a social mechanism ensuring the circulation of women, alliances, and resources between groups. By studying variations in incest taboos across societies, she demonstrated that they reflect each culture’s attempt to balance kinship continuity with social expansion.

Héritier also interpreted incest prohibitions through the lens of symbolic thought, linking them to ideas of purity, lineage, and control over reproduction. She emphasised how such prohibitions serve to delineate moral and social boundaries, defining who belongs within and outside a community. In this context, the regulation of desire is inseparable from the regulation of power: by determining who may marry or reproduce with whom, societies establish a hierarchy of legitimacy that extends far beyond the family. Her analysis highlighted how even the most intimate aspects of human life are structured by cultural logic.

Symbolic Thought and the Construction of Meaning

Like Lévi-Strauss, Héritier believed that human societies are structured by symbolic systems — networks of oppositions and analogies that organise experience. However, she sought to refine structuralism by emphasising the dynamic interplay between biological facts and symbolic interpretation. She argued that culture arises from humanity’s need to impose meaning on natural differences — including sex, age, and kinship. Her work thus explored how categories such as male/female or life/death are universal in structure but culturally specific in expression.

Through her analyses, Héritier revealed how these symbolic structures underpin institutions, moral codes, and even emotional life. She demonstrated that myths, rituals, and social norms are not random inventions but expressions of fundamental cognitive patterns. Yet she also stressed that symbolic systems are not immutable; they evolve as societies reinterpret the meanings attached to human experience. This recognition allowed her to reconcile structuralist theory with historical and social change, positioning her as a bridge between classical anthropology and contemporary cultural studies.

Violence and Power

Héritier’s reflections on violence extended her anthropological inquiry into the realms of ethics and politics. In De la violence, she argued that violence is not an accidental deviation from social order but one of its conditions of possibility. She traced the roots of violence to the human desire for domination and differentiation, showing how it manifests in both interpersonal conflict and institutional inequality. For her, violence is inseparable from symbolic systems that justify hierarchy — particularly gender hierarchy.

By examining forms of physical, sexual, and symbolic violence, Héritier connected anthropological theory to pressing contemporary issues such as war, patriarchy, and systemic injustice. She challenged the notion that violence belongs only to “primitive” societies, instead suggesting that modern institutions reproduce it in subtler, more rationalised forms. Her work thereby contributed to a deeper understanding of how domination persists not only through force but also through cultural representations that legitimise inequality.

The Relationship between Biology and Culture

A recurring theme throughout Héritier’s career was the complex relationship between biological facts and cultural interpretation. She rejected both biological determinism and cultural relativism, arguing that human life is always shaped by the interplay of natural and symbolic dimensions. Her analysis of reproduction and sexuality exemplified this perspective: while biological differences between the sexes are real, their meanings and consequences are socially constructed. She thus opened new paths for studying how societies transform nature into culture.

Héritier’s interdisciplinary approach drew on anthropology, psychoanalysis, and cognitive science to explore how humans interpret their own bodies. She maintained that it is in this mediation between biology and culture that humanity’s creativity — and its capacity for inequality — resides. By making this connection central to her thought, she anticipated many contemporary debates on gender, identity, and the body, ensuring that her work remains relevant to modern discussions in both the social sciences and the humanities.

4) Héritier as Anthropologist

Françoise Héritier’s place within anthropology is both foundational and transformative. As one of the foremost heirs to Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structuralist legacy, she not only preserved the analytical rigour of the structuralist method but also expanded it to encompass new dimensions of human experience — particularly gender, emotion, and the body. Her anthropology was grounded in the conviction that human societies, regardless of their diversity, share deep structural logics that govern thought and behaviour. Yet she moved beyond the purely formal analysis of systems to consider how symbolic structures interact with lived realities. In doing so, she gave anthropology a renewed ethical and political scope, showing that it could illuminate both ancient customs and modern inequalities.

Her early ethnographic work in West Africa was instrumental in shaping her anthropological vision. Working among the Samo, Mossi, and other groups, she studied kinship systems with extraordinary precision, uncovering the ways social structures organise reproduction, inheritance, and marriage. Unlike earlier anthropologists who treated kinship as a technical classification, Héritier approached it as a field where biology, emotion, and culture intersect. Her close observation of women’s roles in these societies led her to question long-held assumptions about the universality of male dominance. This ethnographic insight would later evolve into her celebrated theory of the differential valence of the sexes, demonstrating how fieldwork could yield conceptual breakthroughs.

Héritier’s anthropological contribution was characterised by her capacity to bridge the empirical and the theoretical. She worked with the minute details of kinship diagrams and genealogical charts but always with the aim of uncovering universal principles of human thought. Her studies of incest prohibitions, for instance, revealed the hidden logic behind social rules that seem arbitrary or moralistic. She showed that such prohibitions are not simply mechanisms for regulating reproduction but also tools for structuring alliance and exchange. By interpreting kinship as both symbolic and pragmatic, she expanded anthropology’s understanding of how societies sustain themselves across generations.

What truly distinguished Héritier as an anthropologist was her insistence on including gender as a structural category of analysis. While Lévi-Strauss had demonstrated that kinship and exchange form the foundation of social order, Héritier pointed out that these systems are built upon the unequal valuation of the sexes. In her view, anthropology could not claim to describe the human condition without addressing the ways in which women’s reproductive capacity is socially managed, controlled, and symbolically appropriated. This insight placed her at the forefront of feminist anthropology, where she demonstrated that the subordination of women is not a contingent social fact but a structural feature of human symbolic thought — one that can nevertheless be transformed.

Héritier also challenged the notion of anthropology as a detached or purely descriptive science. She believed that understanding human societies entailed ethical responsibility — the obligation to question the systems of thought that sustain inequality. Through her writings and teaching at the Collège de France, she urged anthropologists to consider how their analyses might contribute to greater social awareness. Her lectures were renowned for their clarity and humanity, combining theoretical precision with an openness to interdisciplinary dialogue. She encouraged her students to see anthropology as a living, self-critical discipline that must evolve alongside the societies it studies.

In this sense, Héritier’s anthropology was both structural and humanist. She sought to uncover the invisible logics that shape human culture, but she never lost sight of individual experience. Her later works, such as Le sel de la vie, reflected this integration of scientific curiosity with personal reflection. By celebrating the richness of ordinary life, she showed that anthropology is not confined to the study of “others” but is also a means of understanding oneself. Her work thus bridged the gap between scientific analysis and the poetry of existence, reaffirming anthropology’s role as a discipline of empathy and imagination.

As a thinker, Héritier’s influence extended beyond academia into the public sphere. She became a respected voice in debates on gender equality, bioethics, and reproductive rights, applying anthropological insight to contemporary moral and political questions. Her ability to connect complex theoretical ideas to everyday issues made her one of France’s most accessible intellectuals. Through her teaching, writing, and public engagement, she demonstrated that anthropology could be both intellectually rigorous and socially transformative.

Françoise Héritier redefined what it means to be an anthropologist. She transformed a discipline often preoccupied with the distant and the exotic into one that reflects critically on universal human experience. By revealing how symbols, hierarchies, and bodies intertwine to shape societies, she helped anthropology speak to the deepest questions of human life — power, identity, and the meaning of difference. Her legacy endures not only in her theories but also in her example of intellectual integrity, compassion, and the belief that understanding humanity is itself a moral act.

5) Her Legacy

Françoise Héritier’s legacy stands as one of the most enduring and transformative in contemporary anthropology and feminist thought. She not only succeeded one of the most influential anthropologists of the twentieth century, Claude Lévi-Strauss, but also redefined the discipline he helped establish. By introducing the concept of the differential valence of the sexes, Héritier expanded structural anthropology to include the symbolic and social mechanisms of gender inequality. This innovation repositioned anthropology as a field deeply engaged with questions of justice, equality, and human value. Her theoretical contributions continue to shape debates in anthropology, sociology, gender studies, and philosophy, ensuring her place among the foremost intellectual figures of modern France.

Her legacy is also inseparable from her pioneering role as a woman in academia. As only the second woman to hold a chair at the Collège de France, she became a symbol of intellectual achievement and perseverance in a domain historically dominated by men. Her ascent represented not just personal success but a broader shift towards inclusivity in the French academic world. Many younger scholars — particularly women — have cited her as a model of integrity, independence, and intellectual courage. Through both her scholarly and institutional achievements, Héritier helped to open anthropology to new perspectives, voices, and experiences that had long been marginalised.

One of the most significant aspects of her legacy lies in the way she reoriented anthropology towards contemporary social relevance. While remaining deeply rooted in structural analysis, she insisted that anthropology should address present-day inequalities and moral dilemmas. Her studies of kinship, gender, and violence were never confined to “traditional” societies but extended to modern forms of domination and exclusion. In doing so, she demonstrated that anthropology could provide tools for understanding not only distant cultures but also the mechanisms of power within our own. Her intellectual engagement in public debates — particularly on bioethics, reproductive rights, and gender equality — exemplified her conviction that knowledge must serve humanity.

Héritier’s influence extended beyond the academy through her capacity to communicate complex ideas to a wide audience. Works such as Le sel de la vie and Le goût des mots showed her versatility as a writer who could translate anthropological reflection into philosophical and poetic language. These later works captured the humanist spirit underlying her entire career: a deep respect for the diversity and creativity of human experience. By combining rigorous analysis with literary sensitivity, she demonstrated that the anthropologist’s task is not only to interpret systems but to celebrate the beauty of human life in all its contradictions.

Her contributions to feminist theory are equally profound. Unlike many contemporaries who approached feminism from sociological or political perspectives, Héritier grounded her feminism in anthropology, tracing the roots of gender inequality to the symbolic order itself. Her theory of the valence différentielle des sexes remains a cornerstone in feminist anthropology, offering an explanation of why patriarchal hierarchies have persisted across time and cultures. By revealing the cultural origins of what is often mistaken for “natural” difference, she gave feminism a powerful anthropological foundation. Her work thus helped to bridge the gap between scientific inquiry and the pursuit of social justice.

Recognition of her achievements came in many forms — from election to the Académie des sciences morales et politiques to numerous literary and scholarly awards. Yet, perhaps her greatest recognition is the continued vitality of her ideas in academic and public discourse. Her insights are now taught across disciplines, influencing not only anthropologists but also philosophers, historians, linguists, and psychologists. The fact that her concepts remain central to discussions of gender, kinship, and symbolic systems testifies to their enduring relevance.

In the broader history of anthropology, Héritier occupies a rare position as both a successor and a reformer. She respected the intellectual foundations of her discipline while daring to question its blind spots, especially its neglect of women’s roles and experiences. Through her work, anthropology evolved from a science of structures into a science of relationships — between bodies, symbols, and power. She made visible what had long been invisible: the ways in which gender and reproduction underpin the social order. Her contribution thus transformed anthropology into a more inclusive and reflective discipline.

Françoise Héritier’s legacy ultimately lies in her vision of humanity as both universal and diverse, structured yet capable of change. She taught that the task of anthropology is not only to understand difference but also to challenge the hierarchies that distort it. In her life and work, she embodied the belief that intellectual inquiry must be guided by ethical awareness. Her thought continues to inspire those who seek to understand the deep roots of inequality and to imagine more balanced and humane ways of living together. Through her ideas, Françoise Héritier remains a vital presence — a thinker who gave anthropology both its conscience and its future.