1) His Biography

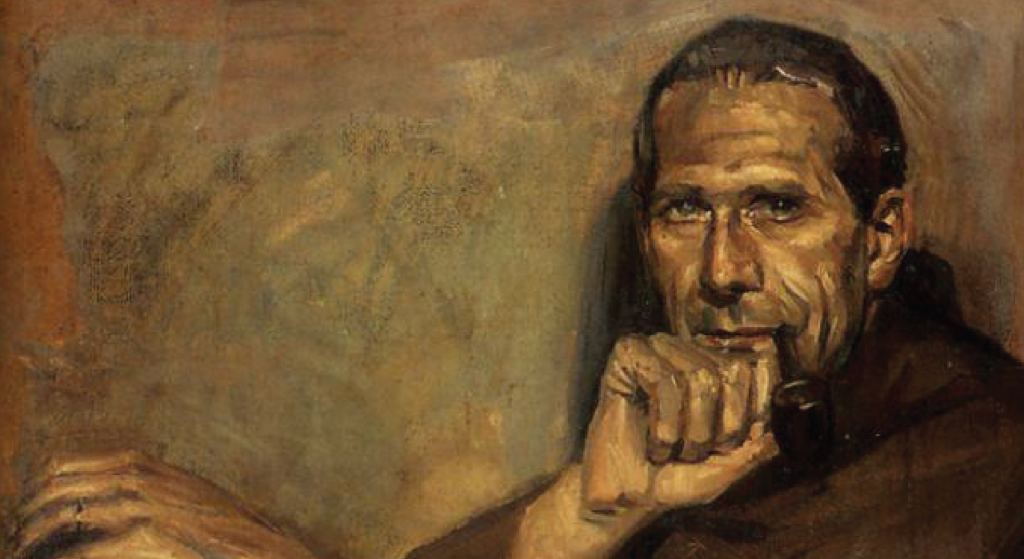

Alfred Sohn-Rethel was born on January 4, 1899, in Paris, into a cultured and intellectually prominent German family. His father, Karl Sohn-Rethel, was a painter, and his uncles included the painter Alfred Rethel and art historian Otto Sohn-Rethel, exposing Alfred early on to the artistic and academic elite of the time. The family’s strong intellectual pedigree helped shape his lifelong commitment to philosophical and socio-economic inquiry. Raised in Germany, he later studied in Heidelberg and Bonn, and it was in these academic environments that he first encountered Marxism and critical theory, which would later form the bedrock of his thought.

During the Weimar Republic era, Sohn-Rethel studied under and interacted with some of the most significant figures of German intellectual life, including Max Weber and Karl Jaspers. He later moved to Frankfurt, where he became associated with the early Frankfurt School, although his relationship with the Institute for Social Research was not formalised in the same way as thinkers like Adorno or Horkheimer. Nevertheless, he maintained close personal and theoretical ties with members of the School, particularly through shared critiques of capitalism and fascism. His philosophical outlook was heavily influenced by Marx, yet he brought a unique epistemological focus that distinguished his work.

In the early 1930s, with the rise of Nazism, Sohn-Rethel, like many other leftist intellectuals, went into exile. He travelled through Switzerland, France, and ultimately England, where he spent much of his exile during the Second World War. This period of displacement had a profound impact on his intellectual development, deepening his critique of fascism and sharpening his interest in the historical role of economic categories in shaping consciousness. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Sohn-Rethel did not hold a long-term academic post during his exile, which meant he worked largely in isolation, developing his ideas over extended periods.

Sohn-Rethel’s major intellectual breakthrough came in his theory of the “real abstraction”, a concept he began formulating in the 1930s but only fully articulated in his post-war writings. This idea offered a novel synthesis of epistemology and Marxist economics, arguing that the abstraction required in exchange relations under capitalism is the origin of abstract thought itself. He proposed that the forms of consciousness characteristic of capitalist societies are materially grounded in the act of commodity exchange. This theory marked a bold intervention into Marxist theory, redirecting attention from class consciousness alone to the very structure of cognition under capitalism.

Despite the originality of his ideas, Sohn-Rethel struggled to find a permanent place within academic institutions. It was not until the late 1960s and early 1970s—when student movements across Europe revived interest in heterodox Marxist theory—that his work gained broader recognition. In 1970, he published his most influential book, Intellectual and Manual Labour, which quickly established him as a unique voice in the field of critical theory. The book was widely read among New Left intellectuals and became especially influential in debates over the nature of ideology, science, and abstraction.

He eventually returned to Germany, where he engaged more actively with the academic and political discourse of the time. Although never central to the Frankfurt School’s institutional framework, he was recognised by many of its leading figures as a critical interlocutor. His work influenced a range of disciplines, from philosophy and sociology to political economy and science studies. He continued to write and lecture until his death, refining his theory of real abstraction and responding to developments in global capitalism.

Alfred Sohn-Rethel died on April 6, 1990, in Düsseldorf. His intellectual legacy, while often considered esoteric, has endured in scholarly circles concerned with the intersection of economy and epistemology. He remains a crucial figure for those seeking to understand how capitalism not only shapes material conditions but also the very categories through which we think. His life and work are a testament to the endurance of critical thought in the face of exile, marginalisation, and political upheaval.

2) Main Works

Intellectual and Manual Labour: A Critique of Epistemology (1970)

This is Sohn-Rethel’s most influential work and the fullest expression of his theory of “real abstraction.” In it, he argues that abstract thought does not arise solely from intellectual contemplation but is rooted in the social act of commodity exchange. He contends that in capitalist societies, the separation between intellectual and manual labour mirrors and reinforces a deeper epistemological division. The book critically engages with the philosophical tradition from Kant to Marx and positions itself as a Marxist epistemology. Sohn-Rethel maintains that capitalism creates a form of knowledge that reflects its own abstract and reified social relations.

Economy and Class Structure of German Fascism (first published 1973, originally drafted in 1932)

This short but highly influential text analyses the socio-economic foundations of Nazism in Germany. Written during the early 1930s but published decades later, the work identifies the alliance between large industrial capital and the fascist state as a core driver of Hitler’s rise. Sohn-Rethel argues that fascism did not arise from irrational masses alone but had clear material and class interests behind it. The essay draws on Marxist class analysis and provides a detailed breakdown of how specific industrial sectors benefited from fascist policies.

Geistige und körperliche Arbeit: zur Theorie der gesellschaftlichen Synthesis (1975)

This German-language companion to Intellectual and Manual Labour deepens his exploration of how societal synthesis—i.e. the way society holds together through forms of labour and cognition—operates in capitalist economies. Here, Sohn-Rethel reflects more explicitly on how abstract forms of thinking emerge as historically specific products of certain economic practices. The work includes additional engagements with classical philosophy and science, adding nuance to his account of epistemology under capitalism.

Soziologische Theorie der Erkenntnis (published posthumously)

This unfinished manuscript, translated as Sociological Theory of Knowledge, was released after Sohn-Rethel’s death. It attempts to offer a systematic presentation of his epistemological theory in sociological terms. The book outlines how forms of knowledge, including logic and mathematics, are not purely intellectual products but emerge from and correspond to specific social practices. Though incomplete, the work reinforces Sohn-Rethel’s broader thesis that material life under capitalism shapes how we know and perceive the world.

Various Essays and Lectures

In addition to his major books, Sohn-Rethel produced numerous essays, often published in leftist journals or collected volumes. Topics included the critique of ideology, the political economy of fascism, and debates within Marxism and philosophy of science. Notable among these is his contribution to discussions around the Frankfurt School, where he distinguished himself by focusing more intently on the material foundations of cognition rather than cultural or psychological phenomena.

The Economy and Class Structure of German Fascism (English translation with commentary)

This English edition of his earlier 1930s work reached a wider audience after its translation and remains an important resource for those interested in Marxist analyses of fascism. It has been used in political theory courses and cited in broader debates about the political economy of authoritarianism. The commentary in this edition helps contextualise Sohn-Rethel’s arguments within the turbulent political backdrop of the Weimar Republic.

3) Main Themes

Real Abstraction

The concept of real abstraction is perhaps Sohn-Rethel’s most significant theoretical innovation. Unlike traditional philosophical abstractions, which are seen as products of mental activity, real abstraction refers to abstractions that occur in practice, specifically in the act of commodity exchange. In capitalist societies, individuals perform abstract operations—such as equating qualitatively different goods through price—without consciously reflecting on them. Sohn-Rethel argues that such real-world abstractions precede and shape intellectual abstraction. This theme underpins his broader critique of idealist epistemology by rooting forms of thought in material economic processes.

The Separation of Intellectual and Manual Labour

Another central theme in Sohn-Rethel’s work is the historical division between intellectual and manual labour, which he sees as a defining feature of class society, and particularly capitalism. This separation leads to a split in social experience, where thinking becomes detached from the practical and sensuous world of physical labour. He argues that this divide is not merely occupational or institutional, but cognitive and epistemological. It helps sustain dominant ideologies and entrenches alienation, as those engaged in intellectual labour often fail to see how their abstract reasoning arises from concrete social relations.

Marxist Epistemology

Sohn-Rethel’s entire project can be understood as an attempt to formulate a Marxist theory of knowledge. He insists that the forms of thought dominant in any society are conditioned by its mode of production. Rather than seeing knowledge as timeless or universal, he situates it historically and socially. His work challenges both positivist science and classical idealism, arguing that they obscure the social origins of cognition. For Sohn-Rethel, knowledge is not simply about the relationship between subject and object, but about the social synthesis through which that relationship becomes intelligible.

The Social Synthesis of Capitalism

The idea of social synthesis refers to how individuals in a capitalist society are connected not directly, but through abstract systems like the market. Sohn-Rethel views capitalism as a society where human relations are mediated through things—commodities, money, institutions—rather than direct social bonds. This abstraction structures how people think, act, and relate to one another. Understanding the nature of this synthesis is crucial, in his view, to understanding capitalist ideology and consciousness. It also explains how social cohesion can be maintained despite profound alienation and fragmentation.

Fascism and Political Economy

Sohn-Rethel devoted considerable effort to analysing the class structure and economic foundations of fascism. He argued that fascism was not a return to feudal irrationalism but a modern response by monopoly capital to the crisis of liberal capitalism. His analysis emphasises the economic rationality behind fascist rule, particularly its service to large industrial capital. This theme highlights how authoritarian regimes can emerge as stabilising forces for capital accumulation, all while appearing ideologically chaotic or reactionary. It underscores Sohn-Rethel’s insistence on linking political formations with underlying class interests.

Historical Materialism and the Origins of Thought

A consistent thread in Sohn-Rethel’s work is his effort to apply historical materialism not just to politics or economics, but to the very structure of thought. He asks how abstract categories like number, identity, and causality could have arisen historically from human social practices. Rather than seeing these as innate or universal, he investigates their origins in specific economic and historical conditions. This approach leads to a materialist reconstruction of epistemology, one that seeks to demystify the origins of formal thought.

Critique of Idealism and Rationality

Sohn-Rethel’s writings often challenge the dominance of idealist philosophy in Western thought, especially the assumption that rationality is autonomous and disembodied. He critiques the legacy of thinkers like Kant and Hegel for detaching epistemology from the real conditions of life. His alternative account insists that rationality is not universal but historically produced through social relations specific to capitalism. This critique also extends to the ideology of scientific objectivity, which he sees as an outgrowth of the capitalist separation between thought and praxis.

4) Sohn-Rethel as Economist

Alfred Sohn-Rethel’s contributions as an economist are often overshadowed by his work in philosophy and epistemology, yet his economic ideas form a crucial part of his intellectual legacy. His approach to economics was distinctively Marxist but also highly innovative in its critique of the conventional understanding of labour, value, and cognition under capitalism. Sohn-Rethel’s focus was not simply on the economic mechanisms of capitalist society but on how these mechanisms influence human consciousness and the very way people think about the world. Through his exploration of real abstraction, he redefined the relationship between economic systems and cognitive processes, presenting an integrated theory that combined economics with epistemology.

At the heart of Sohn-Rethel’s economic thought was his critique of commodity exchange. While Marx had already outlined the relationship between labour and value in capitalist societies, Sohn-Rethel expanded on this by arguing that commodity exchange does more than determine prices—it creates abstract categories of thought that shape human consciousness. For Sohn-Rethel, the act of exchange itself is a real abstraction, meaning that the abstract concepts necessary for exchange—such as equivalence, value, and market calculation—are not merely mental constructs but are grounded in material social practices. In this way, economics becomes not only a study of material wealth but also a study of how capitalist systems condition the way people perceive and relate to the world around them.

In his work, Sohn-Rethel offered a sophisticated analysis of the economic division of labour, particularly the separation between intellectual and manual labour, which he saw as a fundamental feature of capitalist society. He argued that in pre-capitalist societies, intellectual work was intimately connected with manual labour. However, as capitalism advanced, these two forms of labour became increasingly distinct. This separation, Sohn-Rethel suggested, was not merely a matter of job specialisation but was fundamental to the structure of capitalist society. Intellectual labour became abstracted from the physical world and was disconnected from the productive processes that create value. This division, he argued, had profound implications not only for the economic organisation of society but for the very ways people thought about work, value, and human potential.

Sohn-Rethel’s critique of economic theory extended beyond Marxism to include a deep questioning of the discipline’s fundamental assumptions. He took issue with classical economics for its tendency to treat economic categories—such as value, labour, and capital—as abstract entities that exist independently of social relations. By contrast, Sohn-Rethel insisted that economic categories must be understood as products of specific historical and social contexts, particularly the conditions created by capitalist production. His work, therefore, sought to bring the material conditions of capitalist society back into focus, offering a critique of an economics that too often abstracted itself from the reality of the social relationships that undergird it.

In his examination of fascism, Sohn-Rethel applied his economic theories to the political and historical dynamics of the early 20th century. He argued that fascism should not be understood merely as a political aberration or a reactionary movement but as a political-economic strategy deployed by monopoly capital to stabilise and expand its power. Fascism, according to Sohn-Rethel, was intimately connected with the development of late-stage capitalism, where industrial capital sought a more direct form of control over the state to ensure its own survival. In this view, fascism was not a retreat into pre-capitalist or feudal systems, as many had assumed, but a product of the contradictions inherent in capitalist development.

Another area where Sohn-Rethel’s economic thought left a mark was in his concept of social synthesis, which refers to the way capitalist society organises and connects people through abstract systems, such as money and markets. In a capitalist economy, social relations are mediated through commodities, and individuals are linked not directly but through these abstract entities. For Sohn-Rethel, this social synthesis was not simply a neutral organisational principle but one that had profound implications for how human beings related to one another and to the world. By abstracting social relations into commodities and markets, capitalism imposes a particular form of order that distances people from each other and from the concrete conditions of their labour.

Sohn-Rethel’s work on the economic basis of human cognition offers a novel contribution to Marxist economics by focusing on how economic systems shape thought processes. His theory of real abstraction suggests that abstract thought—such as the concept of equivalence in exchange or the idea of value—is not a product of intellectual activity alone, but is rooted in the material practices of capitalism. This materialist epistemology bridges the gap between economic practice and cognitive theory, providing a unique way of understanding how economic systems influence not only the material conditions of life but also the way individuals think, reason, and understand their world.

Through these contributions, Alfred Sohn-Rethel provides a deeper understanding of the connections between economics, labour, and cognition in capitalist societies. His work calls attention to the often-overlooked ways that economic systems shape not only the material world but also the intellectual and cultural dimensions of human life. His radical Marxist approach remains influential in contemporary discussions on the nature of capitalism, value, and consciousness.

5) His Legacy

Alfred Sohn-Rethel’s intellectual legacy, while somewhat marginal in the broader history of Marxist thought, has had a profound impact on critical theory, philosophy, and economics, especially in the latter half of the 20th century. His work, which bridged the gap between Marxist economics and epistemology, provided a unique lens through which to view the relationship between capitalist social structures and the ways in which we think and know. His contributions have been particularly influential among those interested in the intersections of materialism, cognition, and social theory. Although Sohn-Rethel’s work was not widely embraced by mainstream academia during his lifetime, his ideas have since gained renewed attention and relevance, particularly in the context of post-structuralism, critical theory, and contemporary Marxist scholarship.

One of Sohn-Rethel’s most lasting contributions is his theory of real abstraction, which continues to be a central theme in contemporary discussions of Marxist epistemology. His argument that abstract thought arises out of material social practices—specifically commodity exchange—has proven to be a powerful tool for understanding the cognitive dimensions of capitalism. The idea that the process of commodity exchange imposes a specific mode of thinking, one that is abstract and detached from material reality, challenges traditional Marxist understandings of ideology and consciousness. Sohn-Rethel’s work invites scholars to reconsider how abstract concepts like value, money, and logic are not merely intellectual constructs but are grounded in the material conditions of capitalist production.

Sohn-Rethel’s critique of the division between intellectual and manual labour also remains an important theme in critical thought. His analysis of how capitalist society divides and separates different kinds of work, and how this separation shapes both economic and cognitive life, continues to resonate in contemporary discussions of labour, automation, and the future of work. In the current era of digital capitalism and gig economies, Sohn-Rethel’s ideas about the relationship between intellectual and manual labour provide a framework for understanding how technological developments are altering the structure of work and how these changes might influence the ways we think about both value and labour.

His analysis of fascism as a product of the political economy of late capitalism has also proven to be prescient. In the decades following Sohn-Rethel’s work, the rise of neoliberalism, the resurgence of far-right populism, and the increasing dominance of multinational corporations have revived interest in his writings on the intersection of economics and authoritarianism. Sohn-Rethel’s work remains a valuable resource for understanding the ways in which capitalist elites can manipulate political ideologies to maintain and consolidate their power, especially during times of crisis. His approach to fascism, which views it as a rational response to the contradictions of capitalism rather than an irrational or purely ideological phenomenon, provides a unique perspective that continues to inform contemporary political analysis.

Sohn-Rethel’s influence also extends beyond Marxist circles, impacting disciplines such as sociology, philosophy of science, and political economy. His critique of idealism and his focus on the material basis of thought have inspired a variety of scholars interested in understanding the social foundations of knowledge. In the philosophy of science, Sohn-Rethel’s ideas about how scientific knowledge is shaped by economic and social conditions align with broader critiques of the objectivity and neutrality of science, especially in the context of debates about science and technology in capitalist societies. His arguments provide a basis for those seeking to understand how economic interests shape not only political decisions but also scientific practices and theories.

In the academic world, Sohn-Rethel’s work has experienced a resurgence in recent decades, particularly in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the rise of critical approaches to global capitalism. His ideas about the role of abstraction in capitalist societies are increasingly seen as relevant to contemporary debates on the nature of capitalism, financialisation, and global inequality. Sohn-Rethel’s analysis of how capitalist systems create forms of knowledge that serve their interests continues to inform critical social theory and has been embraced by a new generation of scholars who are concerned with the ideological underpinnings of capitalist hegemony.

Despite his intellectual isolation during much of his life, Sohn-Rethel’s legacy is now more secure, thanks to the growing interest in his work and the way his ideas resonate with current socio-political developments. He is increasingly recognised as a key figure in Marxist theory, not only for his unique contributions to epistemology but also for his capacity to link economic structures with the development of human cognition and consciousness. His ideas offer a powerful challenge to both traditional economic theory and dominant epistemological frameworks, reminding us that the structures of capitalist society shape not only what we produce and consume but also the very ways in which we understand and engage with the world.

Today, Sohn-Rethel’s influence continues to be felt in critical Marxist thought, especially in areas such as the philosophy of history, the critique of ideology, and the analysis of global capitalism. His work remains a vital resource for those interested in the intersections of economics, epistemology, and politics. As capitalism continues to evolve and new forms of ideological and economic control emerge, Sohn-Rethel’s ideas provide a crucial framework for understanding how thought itself is shaped by the material conditions of society.