1) Her Biography

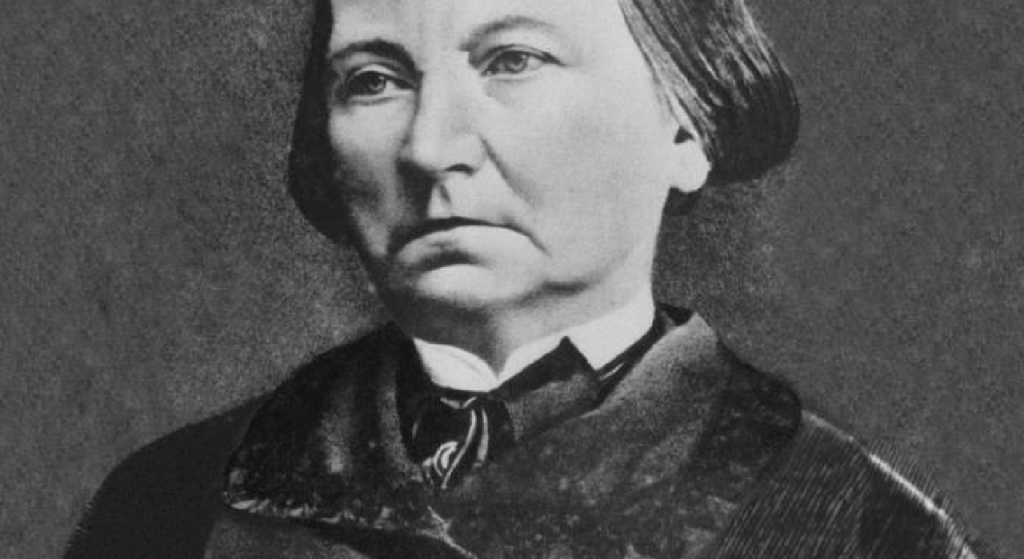

Concepción Arenal was born on 31 January 1820 in Ferrol, a town in the northwestern region of Galicia, Spain. Raised in a liberal household, she was deeply influenced by her father, Ángel del Arenal, a lawyer and writer with progressive ideals who had suffered political persecution under the absolutist regime of Ferdinand VII. His early death had a profound impact on her, shaping her lifelong commitment to justice and human dignity. Arenal’s early education was somewhat unconventional; she reportedly dressed as a man to attend lectures at the University of Madrid, a reflection of both her rebellious spirit and the restrictive educational environment for women at the time.

Despite facing systemic barriers as a woman, Arenal pursued an impressive intellectual path. She earned a law degree at a time when women were formally barred from legal studies and participated actively in the literary and philosophical circles of Madrid. Her early writings, including poetry and essays, revealed a unique blend of romantic sentiment and rational moral inquiry. This period marked the beginning of her engagement with the social issues that would come to define her legacy—most notably, her concern for the poor, prisoners, and the marginalised in Spanish society.

Arenal’s career as a writer and thinker flourished in the mid-nineteenth century, when she began publishing essays that merged moral philosophy with social critique. In 1864, she was appointed Inspector of Women’s Correctional Facilities, a rare public role for a woman at the time. This appointment allowed her to combine practical reform efforts with theoretical reflection, resulting in a body of work that was grounded in both institutional experience and ethical analysis. Her approach was notably humanitarian, focusing not on punishment but on rehabilitation and moral education.

Throughout her life, Arenal was deeply committed to Christian ethics, but she rejected dogmatic or institutionalised religion in favour of a more personal, rational spirituality. This perspective infused her writings with a unique tone—moral yet progressive, spiritual yet grounded in social realities. She argued forcefully for women’s rights, education reform, and the humane treatment of prisoners. Her emphasis on compassion and reason placed her in dialogue with both liberal and religious reformers, although she often found herself at odds with prevailing conservative norms.

Her intellectual and professional achievements were accompanied by personal challenges, including widowhood and the burden of raising children on her own. Nonetheless, Arenal remained active in her advocacy until the end of her life, participating in international conferences and engaging with the broader European discourse on penal reform and social justice. Her writings were well regarded in progressive circles and translated into several languages, extending her influence beyond Spain.

Arenal’s life was a remarkable blend of courage, intellectual depth, and moral conviction. She was not merely a commentator on the social issues of her time but an active agent of change, advocating tirelessly for reforms in law, education, and prison systems. Her role as a pioneering feminist and social theorist set her apart in a century when women’s voices were largely excluded from public discourse. She challenged both the Spanish state and the Catholic Church to recognise the moral agency and dignity of all individuals, regardless of gender or social status.

She died in Vigo in 1893, leaving behind a substantial body of work that included philosophical essays, legal treatises, and journalistic writings. Over time, she came to be recognised as one of the foundational figures of Spanish liberal thought and feminist theory. Her legacy continues to inspire scholars, activists, and reformers interested in the intersection of ethics, law, and social justice. Institutions and awards bearing her name serve as a testament to the enduring relevance of her ideas.

2) Main Works

La Beneficencia, la Filantropía y la Caridad (1861)

In this foundational work, Arenal explores the distinctions between beneficence, philanthropy, and charity, advocating for a more structured and ethical approach to aiding the poor. She criticises haphazard or emotionally driven acts of giving and instead promotes rational, institutional responses that uphold the dignity of the recipient. Drawing from both Catholic teachings and Enlightenment reasoning, she frames social welfare as a moral duty rather than an optional virtue. The book laid the groundwork for modern Spanish social work and public assistance, merging theological compassion with legal and administrative rigour.

Cartas a los Delincuentes (Letters to Criminals) (1865)

This work exemplifies Arenal’s humane approach to penal reform. Presented in the form of letters, the text addresses incarcerated individuals directly, offering moral encouragement and philosophical reflection. She argues that prisoners are not irredeemably bad but are often victims of social neglect, ignorance, or circumstance. Arenal seeks to instil a sense of worth and possibility in her readers, urging society to look beyond punishment and towards rehabilitation. Her compassionate tone and reformist spirit made the book influential in discussions on criminal justice throughout Spain and Europe.

El Visitador del Pobre (The Visitor of the Poor) (1863)

This practical guide offers advice to those engaging in charitable work, particularly volunteers who visited the poor and sick. Arenal stresses the importance of tact, empathy, and respect, cautioning against paternalism or intrusive moral judgement. She encourages a relationship of solidarity rather than hierarchy, insisting that the poor should not be treated as objects of pity but as fellow citizens. The work reflects her consistent emphasis on the ethical obligations that accompany philanthropy and remains one of her most accessible and instructive texts on social ethics.

La Mujer del Porvenir (The Woman of the Future) (1869)

In this powerful feminist treatise, Arenal lays out her vision for women’s emancipation through education, legal rights, and active participation in public life. She challenges the deeply patriarchal structures of Spanish society and calls for a reevaluation of women’s intellectual and moral capacities. The work is steeped in both rationalist and Christian ideals, as she argues that gender equality is not only a political necessity but a moral imperative. It represents one of the earliest articulations of Spanish feminist thought and inspired later generations of women reformers.

Estudios Penitenciarios (Penitentiary Studies) (1877)

A more technical and policy-oriented book, Estudios Penitenciarios presents a comprehensive critique of the Spanish prison system and proposes detailed reforms. Arenal draws upon empirical observations made during her work as a prison inspector and supports her arguments with legal theory and ethical reasoning. The text examines the psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of incarceration, aiming to create a more humane and effective model of justice. It had a significant influence on both national and international debates about penitentiary reform in the 19th century.

La Instrucción del Pueblo (The Education of the People) (1881)

This educational manifesto argues for universal and secular education as a cornerstone of a just and rational society. Arenal links ignorance with social inequality, crime, and moral decline, making the case that education is essential for both individual development and national progress. The book includes critiques of the educational system of her time, as well as proposals for reform, particularly regarding the inclusion of women and the working class. Her vision anticipates many of the educational reforms that would be implemented in Spain in the 20th century.

Oda a la esclavitud (Ode to Slavery) (1845)

Though lesser known than her essays, this early poetic work offers a searing condemnation of slavery and colonial injustice. Using powerful romantic imagery and rhetorical force, Arenal attacks the moral hypocrisy of a society that claimed to be Christian while permitting such inhuman practices. The piece reveals her early commitment to universal human rights and social equality, themes that would reappear throughout her later prose writings. It also illustrates her ability to blend literary and political expression with striking emotional intensity.

3) Main Themes

Social Justice and Moral Responsibility

Arenal consistently emphasised the moral duty of individuals and institutions to address social inequality. Her works call for justice not as mere legal fairness but as an ethical imperative that involves compassion, respect, and active intervention in the lives of the poor and marginalised.

Reform of the Penal System

She advocated for the rehabilitation of prisoners rather than punitive measures. Arenal viewed crime as a social issue, often rooted in poverty and lack of education, and argued that prisons should focus on reforming the individual through humane treatment, education, and moral guidance.

Women’s Rights and Gender Equality

A central theme in her writings is the need for women’s emancipation through education and legal recognition. Arenal challenged traditional gender roles and argued for women’s intellectual and moral capacities, making her one of the pioneering feminist voices in 19th-century Spain.

Philanthropy and Ethical Charity

She drew careful distinctions between charity, philanthropy, and true beneficence. Arenal encouraged thoughtful, structured, and respectful forms of aid that preserved the dignity of the recipient, warning against superficial or condescending acts of giving.

The Importance of Education

Education, for Arenal, was the foundation of a just society. She viewed it as a means of moral and civic development, not merely intellectual advancement. Her advocacy extended to all classes and genders, stressing that ignorance was a root cause of many societal ills.

Christian Humanism

Her worldview was deeply shaped by Christian ethics, though she rejected dogma. Arenal believed in a rational, active form of Christianity that emphasised compassion, social responsibility, and the inherent worth of every individual, often positioning her between liberal and religious thinkers.

Individual Dignity and Moral Agency

Across her works, Arenal upheld the idea that every person, regardless of social status or criminal record, possesses intrinsic dignity and the potential for moral growth. This belief underpinned her approach to law, education, and philanthropy, and guided her reformist agenda.

Critique of Institutional Injustice

She regularly criticised the failures of the state, church, and judiciary to protect the vulnerable. Arenal was unafraid to confront institutional power, calling for systemic changes that aligned with ethical principles and practical reason.

4) Arenal as a Social Worker

Concepción Arenal stands as one of the earliest and most influential figures in the development of social work in Spain, even before the profession was formally recognised. Her approach combined practical action with deep philosophical and moral reflection, making her not only a reformer but also a theorist of social assistance. Arenal’s work as a prison inspector, a writer on poverty and education, and a public intellectual exemplified a profound commitment to the wellbeing of society’s most vulnerable members. She rejected charity as mere almsgiving and instead championed an ethic of structural change and moral responsibility.

Her work as Inspector of Women’s Correctional Facilities from 1864 provided her with first-hand experience of institutional failures, particularly those relating to women. Rather than viewing prisoners as lost causes, she considered them capable of redemption and deserving of humane treatment. This belief translated into calls for rehabilitation-oriented prison systems that offered educational and spiritual development. Her hands-on engagement with incarcerated women marked a departure from the detached, punitive attitudes common in 19th-century legal thought. She brought compassion and a sense of ethical urgency to a space that had previously been governed by indifference and control.

Arenal’s theoretical work in social care centred on the dignity of the individual. Her distinction between beneficencia, filantropía, and caridad was more than semantic; it was foundational to her vision of social support. She viewed charity as often patronising or morally shallow, while beneficence demanded a structured, enduring commitment to justice. She urged that aid be rooted in understanding, respect, and long-term solutions rather than one-time gestures. In doing so, she laid the intellectual groundwork for modern welfare policies and ethical standards in social work.

Her method as a social worker was interdisciplinary, drawing upon law, philosophy, theology, and empirical observation. Arenal believed that addressing social problems required a holistic understanding of their causes, including structural poverty, educational deficits, and legal discrimination. She integrated these perspectives in her writings, particularly in works such as El Visitador del Pobre, which served as a manual for those involved in fieldwork among the poor. The guide promoted empathy, discretion, and humility—qualities she considered essential to ethical intervention.

Moreover, Arenal was a passionate advocate for professionalising social work. Though the concept of “social worker” did not yet exist in her time, her efforts to train volunteers and publish detailed handbooks on poor relief indicated her desire to create an educated, morally grounded corps of reformers. She understood that good intentions alone were insufficient without training and ethical principles. Her belief in the need for preparation and institutional support for those engaging in social work remains a cornerstone of the field today.

She also brought attention to the intersection of social work and feminism. Arenal frequently addressed the double marginalisation faced by poor women and female prisoners. She argued for a gender-sensitive approach to social intervention, recognising the compounded disadvantages that women experienced in education, employment, and justice systems. This aspect of her work was remarkably progressive and contributed to the later integration of gender theory into social services.

Finally, Arenal’s impact as a social worker was not limited to Spain. Her ideas circulated through European reformist circles and influenced broader discussions on the ethics of social assistance. She participated in international conferences and engaged with foreign thinkers, building bridges between Spanish thought and wider humanitarian discourses. In doing so, she contributed to the early internationalisation of social work as a discipline grounded in both moral philosophy and practical compassion. Her legacy continues to inform debates on justice, dignity, and ethical intervention in contemporary welfare systems.

5) Her Legacy

Concepción Arenal’s legacy is both profound and multifaceted, spanning the fields of law, feminism, social work, literature, and moral philosophy. She is widely regarded as one of the foundational figures of modern Spanish thought, particularly in her commitment to human dignity and justice. Although she worked during a time when women’s participation in public and intellectual life was severely limited, Arenal carved out a space for herself through resilience, scholarship, and ethical conviction. Her ideas not only challenged the norms of her era but also anticipated reforms that would only be realised decades later.

In the field of social work, Arenal is frequently acknowledged as a pioneer. Her belief in structured, respectful, and ethical intervention set the stage for what would become the professionalisation of social assistance. She approached social issues with a rigorous and systemic mindset, insisting that poverty, crime, and inequality were not individual failings but societal problems that demanded institutional responses. Her publications served as manuals for future generations of social workers and laid the conceptual foundations for public welfare in Spain and beyond.

Her contributions to feminist thought have earned her a prominent place among the early advocates for women’s rights in the Spanish-speaking world. She did not call for revolution, but rather reform grounded in both reason and morality. Through works such as La Mujer del Porvenir, she exposed the contradictions of a society that denied women educational and legal equality while claiming moral superiority. Her moderate yet intellectually forceful feminism inspired later thinkers such as Emilia Pardo Bazán and Clara Campoamor, who expanded upon her call for women’s civic inclusion.

In the realm of penal reform, her legacy is particularly enduring. Arenal’s insistence on the potential for rehabilitation and her critique of purely retributive justice models helped shift Spanish and European attitudes toward incarceration. Her influence can be traced in the reforms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that introduced educational and psychological programmes into prisons. The humane vision she articulated resonates with current debates on restorative justice and prison abolition, affirming the contemporary relevance of her thought.

Institutions across Spain bear her name, including schools, social service organisations, and academic programmes. The Concepción Arenal Prize is awarded annually to individuals or organisations working to promote human rights and social justice, further cementing her legacy as a reformer and humanitarian. Statues and memorials honour her in cities such as Madrid and Ferrol, while her writings continue to be studied in academic curricula focusing on gender studies, social theory, and law.

She also holds a symbolic role in Spanish cultural memory as an emblem of moral courage and intellectual independence. Her ability to blend Christian ethics with rational critique appealed to both liberal and religious audiences, enabling her ideas to endure across political and ideological divides. This adaptability has helped preserve her relevance across shifting social and political landscapes, from the liberal movements of the 19th century to contemporary feminist and social justice movements.

Internationally, Arenal’s work is increasingly recognised in the broader context of European thought. Though she was often excluded from canonical philosophical lists due to her gender and practical focus, recent scholarship has re-evaluated her as a key figure in the history of applied ethics and reformist philosophy. Her influence has extended into Latin America as well, particularly through Catholic reform circles and feminist educators who found in her a model of moral and intellectual integrity.