1) What is Geoeconomics?

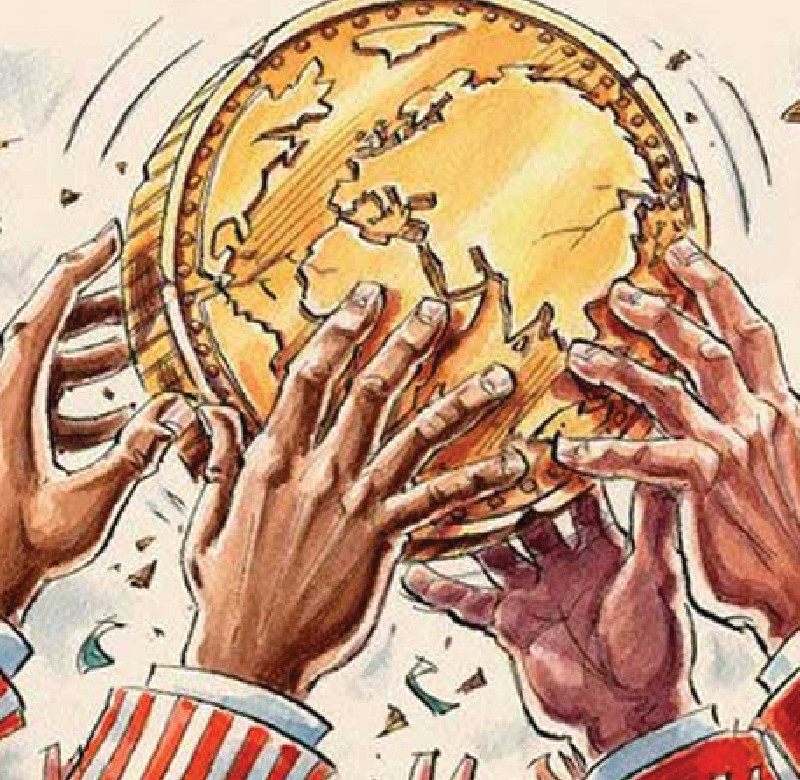

Geoeconomics is a field of study and practice that explores the intersection of economics and geopolitics. Unlike traditional economics which primarily focuses on market forces and domestic policies, geoeconomics takes into account how economic decisions and strategies are influenced by political considerations and how they, in turn, influence political outcomes on a global scale. It emphasises the use of economic instruments, such as trade, investment, sanctions, and aid, as tools to achieve geopolitical objectives or to enhance national security.

In essence, geoeconomics recognises that economic power is not just about wealth and prosperity but also about strategic influence and national security. It encompasses a wide range of activities including trade negotiations, financial diplomacy, economic sanctions, and the management of global supply chains. Countries often engage in geoeconomic strategies to achieve goals such as gaining market access, promoting their industries, or weakening rivals economically.

Geoeconomics also analyses how states use economic tools to shape the behaviour of other states or non-state actors. For example, countries may impose sanctions to deter certain actions or to punish behaviour perceived as harmful to their interests. Moreover, geoeconomic strategies can involve leveraging economic interdependencies to create advantages or to mitigate risks in international relations.

Overall, geoeconomics is increasingly important in today’s interconnected world where economic power and geopolitical influence are closely intertwined. Understanding geoeconomics helps policymakers navigate complex international dynamics where economic considerations are as critical as military and diplomatic ones in shaping global outcomes and ensuring national security.

2) George Chisholm, Father of Geoeconomics:

George Chisholm is widely regarded as the “Father of Geoeconomics” due to his pioneering contributions to the field, particularly through his influential work in the late 20th century. Chisholm, a British economist and scholar, recognised the evolving global landscape where economic dynamics were increasingly shaping geopolitical outcomes. His insights were instrumental in formalising geoeconomics as a distinct area of study and practice.

Chisholm considered geoeconomics important because he saw that traditional economic theories often overlooked the strategic implications of economic policies and interactions among nations. He believed that economic power, wielded through trade, investment, and financial instruments, was becoming as significant as military power in influencing global affairs. By introducing geoeconomics, Chisholm aimed to bridge the gap between economics and geopolitics, advocating for a more holistic understanding of how states pursue their national interests through economic means.

One of Chisholm’s key contributions was his emphasis on the strategic use of economic tools to achieve geopolitical objectives. He argued that economic policies and decisions could be leveraged to strengthen a country’s position on the world stage, enhance its security, and influence the behaviour of other states. This perspective challenged the conventional wisdom that economics and politics operated in separate spheres, advocating instead for an integrated approach where economic strategy and geopolitical strategy were mutually reinforcing.

Moreover, Chisholm’s work underscored the importance of analysing global economic interdependencies and their implications for national security. He highlighted how economic vulnerabilities, such as dependence on critical imports or exposure to financial crises, could pose significant risks to a country’s strategic interests. By understanding these dynamics, Chisholm argued, policymakers could develop more robust strategies to safeguard national security and advance their geopolitical goals.

3) Geoeconomics vs Political Economy:

Geoeconomics and political economy are both fields that examine the intersection of economics and politics, but they differ significantly in their focus and scope.

Political economy traditionally explores the relationship between economic systems, institutions, and actors within a political framework. It seeks to understand how political institutions and processes influence economic policies, distribution of resources, and outcomes such as growth, inequality, and development. Political economy analyses often delve into ideologies, power dynamics, and historical contexts to explain economic phenomena and policy decisions.

On the other hand, geoeconomics specifically examines the strategic use of economic tools and instruments by states to achieve geopolitical objectives. Unlike political economy, which may have a broader focus on domestic economic policies and societal impacts, geoeconomics concentrates on how nations deploy economic resources and policies in pursuit of national security, strategic influence, and geopolitical advantage. It emphasises the role of economic statecraft, including trade negotiations, sanctions, financial diplomacy, and the management of global supply chains, as instruments of geopolitical strategy.

In essence, the main difference lies in their primary focus: political economy centres on the study of economic systems and policies within a political context, while geoeconomics zooms in on the strategic dimensions of economic interactions among states in the international arena. Political economy tends to analyse how domestic political factors shape economic decision-making and outcomes, whereas geoeconomics explores how economic decisions and strategies are used as tools of statecraft to achieve geopolitical goals and influence global power dynamics.

Furthermore, geoeconomics is inherently forward-looking and policy-oriented, often guiding state behaviour in response to geopolitical challenges and opportunities. It seeks to understand how economic leverage can be maximised to enhance a country’s security, assert influence, or weaken adversaries economically. In contrast, political economy may focus more on understanding historical patterns, theoretical frameworks, and systemic relationships between political and economic institutions.

Overall, while both geoeconomics and political economy explore the complex interactions between economics and politics, geoeconomics stands out for its strategic focus on the instrumental use of economic power in international relations, whereas political economy takes a broader view of the political determinants and consequences of economic policies within domestic and international contexts.

4) Geoeconomics and War:

Geoeconomics, as a concept, intersects with the notion of war in several critical ways, shaping contemporary strategies and dynamics in international relations. Unlike traditional military conflict, which primarily involves armed confrontation, geoeconomics introduces the concept of economic statecraft — the use of economic tools and resources as instruments of power projection and influence. Here, we explore how geoeconomics and war relate, focusing on economic strategies, coercion, and the evolving nature of conflict in the modern era.

Firstly, geoeconomics offers states alternative avenues to achieve strategic objectives without resorting to direct military engagement. Economic tools such as sanctions, trade policies, investment strategies, and financial diplomacy can exert significant pressure on adversaries, coercing them to alter their behaviour or policies. This form of economic coercion is often preferred over military action due to its potentially lower cost, reduced human casualties, and broader international legitimacy.

Moreover, geoeconomics plays a crucial role in shaping the economic resilience and vulnerabilities of nations during times of conflict or heightened geopolitical tensions. States may engage in economic warfare by targeting key sectors of an adversary’s economy through sanctions or trade restrictions, aiming to weaken their economic base and undermine their ability to sustain military operations or political stability. Conversely, countries also seek to strengthen their own economic defences, diversify supply chains, and reduce dependencies that could be exploited during conflicts.

Furthermore, the integration of geoeconomics with military strategy has become increasingly pronounced in contemporary warfare doctrines. Modern conflicts often involve a blend of conventional military operations with economic measures designed to support military objectives or undermine the adversary’s capacity to resist. This hybrid approach recognises the interconnectedness of economic and military power in shaping strategic outcomes on the battlefield and in global politics.

In addition, geoeconomics influences post-conflict reconstruction and stability efforts. Economic aid, trade incentives, and investment programmes are deployed to rebuild war-torn regions, stabilise fragile states, and consolidate geopolitical influence in strategically significant regions. These economic initiatives not only aim to foster stability and development but also serve as tools of soft power projection, shaping long-term alliances and partnerships in a post-war geopolitical landscape.

Overall, geoeconomics and war are intricately linked in the modern geopolitical arena, where economic considerations increasingly influence strategic decision-making alongside traditional military factors. Understanding the role of economic statecraft in conflict management, resolution, and post-war reconstruction is essential for policymakers and strategists navigating the complexities of 21st-century international relations. As such, the integration of geoeconomic principles into broader security doctrines underscores the evolving nature of warfare and the strategic imperative of leveraging economic power in pursuit of national interests and global influence.

5) Its Criticisms:

Despite its strategic appeal and growing prominence in international relations, geoeconomics also faces several criticisms and challenges that warrant consideration.

One of the primary criticisms of geoeconomics revolves around the ethical implications of using economic instruments as tools of coercion or influence. Critics argue that economic sanctions and trade restrictions, often employed in geoeconomic strategies, can disproportionately harm civilian populations, exacerbate humanitarian crises, and undermine principles of international law and sovereignty.

Geoeconomic measures, such as sanctions, may have unintended economic and political consequences. For instance, targeted sanctions intended to pressure regimes or entities can lead to unintended economic hardships for broader populations, destabilise regional economies, or provoke retaliatory actions that escalate tensions rather than resolve conflicts.

Geoeconomic strategies operate in a complex and interconnected global economy, where outcomes are often difficult to predict with certainty. Economic interdependencies and the responses of targeted countries or entities can create unforeseen ripple effects, making it challenging for policymakers to anticipate and manage the full spectrum of consequences.

Critics argue that while geoeconomics may achieve short-term geopolitical goals, it may not always be economically efficient or sustainable in the long run. Economic sanctions, for example, can disrupt global trade networks, increase transaction costs, and dampen overall economic growth, potentially undermining the economic interests of the sanctioning country and its allies.

Geoeconomic strategies can provoke retaliatory actions from targeted countries or alliances, leading to a cycle of economic reprisals and escalating tensions. This tit-for-tat dynamic can erode trust, hinder diplomatic efforts, and complicate efforts to find peaceful resolutions to conflicts.

There is ongoing debate about the effectiveness of geoeconomic tools compared to traditional military or diplomatic strategies. Critics argue that economic coercion may not always achieve desired policy outcomes, especially if targeted countries find alternative sources of support or develop resilience to external pressures.

Geoeconomics operates in a relatively unregulated and fluid domain compared to traditional military and diplomatic arenas. This lack of a clear institutional framework and agreed-upon rules for economic statecraft can contribute to uncertainties and disparities in how geoeconomic strategies are applied and perceived globally.

While geoeconomics offers states powerful means to achieve strategic objectives through economic leverage, it also faces significant criticisms regarding its ethical implications, unintended consequences, complexity, economic efficiency, geopolitical backlash, effectiveness, and the absence of a robust institutional framework. Addressing these critiques requires careful consideration of the broader impacts of geoeconomic strategies and a balanced approach that integrates economic statecraft with other tools of international relations.