John Keats

1) His Biography

John Keats, born on 31 October 1795 in London, is one of the most beloved and influential poets of the Romantic era. The son of Thomas and Frances Keats, John was the eldest of four surviving children. His father managed the Swan and Hoop Inn, a livery stable, which provided a reasonably comfortable life for the family. However, tragedy struck early in Keats’s life; his father died in a riding accident in 1804, and his mother succumbed to tuberculosis in 1810. These events profoundly affected Keats, shaping his views on mortality and human suffering.

After his mother’s death, Keats and his siblings were placed under the guardianship of Richard Abbey and John Sandell, who ensured that Keats received a decent education. Keats attended Clarke’s School in Enfield, where he developed a love for literature and classical studies. His headmaster, John Clarke, played a significant role in nurturing Keats’s literary interests, introducing him to the works of Spenser and other poets. This period of education laid the groundwork for Keats’s future poetic endeavours.

In 1810, at the age of fifteen, Keats left school to become an apprentice to Thomas Hammond, a surgeon and apothecary in Edmonton. This apprenticeship marked the beginning of Keats’s medical career, which he pursued with dedication despite his burgeoning passion for poetry. In 1815, he moved to London to continue his medical training at Guy’s Hospital. Keats’s time in the medical field was brief but intense; he was diligent and competent, yet his heart increasingly yearned for the world of poetry.

Keats’s literary journey began in earnest in 1816, when he published his first poem, “O Solitude! if I must with thee dwell,” in Leigh Hunt’s Examiner. Hunt, a poet and critic, became an important mentor and friend to Keats, encouraging him to devote himself to poetry. This encouragement bore fruit, and in 1817, Keats published his first volume of poetry, Poems by John Keats. Though the volume did not achieve commercial success, it marked Keats’s entrance into the literary world and demonstrated his potential as a poet.

The following years were both productive and challenging for Keats. In 1818, he embarked on a walking tour of Scotland, Ireland, and the Lake District with his friend Charles Armitage Brown. This journey, though physically taxing, provided Keats with inspiration and material for his poetry. Upon returning, he faced personal and financial difficulties, including the illness of his brother Tom, who was suffering from tuberculosis. Keats nursed Tom until his death in December 1818, a period that deepened his understanding of human suffering and loss.

Despite these hardships, Keats’s most creative period was just beginning. From 1818 to 1820, he composed many of his most famous works, including the odes “To Autumn,” “Ode to a Nightingale,” and “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” These poems, characterised by their rich imagery and emotional depth, are considered masterpieces of English literature. During this time, Keats also fell in love with Fanny Brawne, a relationship that brought him both joy and anguish, as his declining health and financial instability made a future with her uncertain.

In early 1820, Keats’s health deteriorated significantly. He began showing symptoms of tuberculosis, the same disease that had claimed his mother and brother. Despite his worsening condition, he continued to write, producing some of his most poignant and reflective poetry. In September 1820, seeking a milder climate for his health, Keats travelled to Italy with his friend Joseph Severn. Sadly, the change of environment did little to improve his condition. John Keats died in Rome on 23 February 1821, at the age of twenty-five, leaving behind a legacy that would grow posthumously.

2) Main Works

Ode to a Nightingale:

“Ode to a Nightingale” is one of Keats’s most celebrated works, composed in May 1819. This poem explores the themes of transience and immortality through the contrast between the ephemeral nature of human life and the seemingly eternal song of the nightingale. Keats begins the poem with a description of his profound sense of melancholy, triggered by the nightingale’s song, which transports him to a realm of imagination and beauty. As the poem progresses, Keats expresses a longing to escape the pains of reality and join the bird in its idealised, untroubled world. However, he ultimately recognises the inevitability of his return to the mortal world. The poem’s rich imagery and emotive language capture the complexity of Keats’s feelings, making it a quintessential Romantic work.

Ode on a Grecian Urn:

Written in May 1819, “Ode on a Grecian Urn” is another of Keats’s major odes, delving into themes of art, beauty, and permanence. The poem reflects on the scenes depicted on an ancient Greek urn, which capture moments of beauty and life frozen in time. Keats marvels at the urn’s ability to preserve these moments forever, contrasting the timeless nature of art with the fleeting nature of human existence. The famous concluding lines, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know,” encapsulate the poem’s central idea that art provides a glimpse into a higher truth, transcending the temporal world. This ode is renowned for its philosophical depth and its exploration of the relationship between life and art.

To Autumn:

“To Autumn,” composed in September 1819, is often considered Keats’s most perfect poem due to its rich sensory imagery and serene tone. Unlike his other major odes, “To Autumn” does not grapple with intense personal emotions or philosophical questions. Instead, it celebrates the season of autumn in all its fullness and maturity. The poem is structured into three stanzas, each depicting a different aspect of autumn: the abundance of the harvest, the labour of gathering, and the tranquil beauty of the season’s end. Keats’s detailed and evocative descriptions create a vivid picture of the natural world, highlighting the harmony and contentment that can be found in accepting the cycles of life. “To Autumn” stands as a testament to Keats’s mastery of language and his ability to find beauty in the everyday.

Endymion:

“Endymion,” published in 1818, is one of Keats’s early works, a long narrative poem that embodies the Romantic spirit of seeking beauty and transcendence. The poem, subtitled “A Poetic Romance,” is based on the Greek myth of Endymion, a shepherd who falls in love with the moon goddess Selene. Over four books, Keats weaves a complex and imaginative tale, exploring themes of love, dreams, and the quest for ideal beauty. Although “Endymion” was criticised for its elaborate language and sometimes uneven structure, it is significant for its ambition and its reflection of Keats’s poetic development. The famous opening line, “A thing of beauty is a joy for ever,” encapsulates the poem’s enduring appeal and its affirmation of the power of beauty.

Lamia:

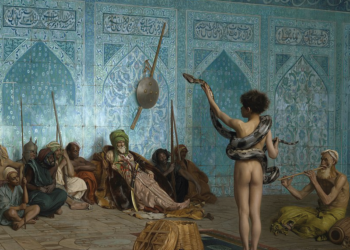

“Lamia,” published in 1820, is another narrative poem by Keats, exploring themes of illusion, transformation, and the conflict between reason and imagination. The poem tells the story of Lamia, a beautiful woman who is revealed to be a serpent in disguise, and her tragic love affair with the mortal Lycius. Keats’s portrayal of Lamia is rich with ambiguity, blending elements of seduction and victimhood, enchantment and deception. The poem’s lush and sensuous descriptions create a vivid and captivating atmosphere, drawing readers into its mythic world. “Lamia” also reflects Keats’s ongoing concern with the relationship between beauty and reality, as well as the dangers of disillusionment. Through its intricate narrative and thematic complexity, “Lamia” stands as a powerful example of Keats’s narrative artistry.

3) Main Themes

Beauty and Truth

One of the most prominent themes in Keats’s poetry is the relationship between beauty and truth. This theme is famously encapsulated in the concluding lines of “Ode on a Grecian Urn”: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Keats suggests that the perception of beauty can lead to a deeper understanding of truth, and vice versa. The idea that beauty is an eternal, transcendent quality contrasts with the fleeting nature of human experience. Keats’s exploration of this theme reflects his belief in the power of art to reveal profound truths, a concept influenced by Platonic ideals. Unlike some contemporaries, such as Wordsworth, who saw beauty in nature as a pathway to spiritual insight, Keats focused more on the aesthetic experience and the intrinsic value of beauty itself. This philosophical stance underscores Keats’s original contribution to Romantic thought, highlighting his unique approach to the interplay between sensory experience and intellectual understanding.

Mortality and Transience

Mortality and the transience of human life are central themes in Keats’s work, deeply influenced by his personal experiences with illness and loss. In “Ode to a Nightingale,” Keats contrasts the ephemeral nature of human life with the nightingale’s seemingly immortal song, expressing a longing for the permanence that life cannot offer. This theme is also evident in “To Autumn,” where the poem’s celebration of the season’s ripeness and decay reflects the natural cycles of life and death. Keats’s treatment of mortality often involves a contemplation of the inevitability of death and the ways in which art and nature can offer solace. Compared to contemporaries like Byron, who often depicted death in a more dramatic and rebellious light, Keats’s approach is more meditative and accepting. His nuanced exploration of transience highlights the poignancy of fleeting moments, contributing to a richer understanding of human vulnerability and resilience.

Imagination and Reality

The tension between imagination and reality is another key theme in Keats’s poetry. In “Lamia,” Keats explores the dangers and delights of illusion, as the protagonist’s enchantment is ultimately shattered by harsh reality. This theme is further examined in “Ode to a Nightingale,” where the poet’s imaginative journey with the nightingale’s song is abruptly interrupted by the return to reality. Keats’s fascination with the power of imagination aligns with the broader Romantic emphasis on creativity and emotional depth. However, his work also acknowledges the limitations and potential pitfalls of living too much in the realm of imagination. This duality distinguishes Keats from other Romantic poets like Coleridge, who often celebrated the imaginative mind’s ability to transcend reality without as much focus on its inevitable return to the mundane. Keats’s balanced perspective offers a more complex view of the human psyche, acknowledging both the escapist allure and the grounding force of reality.

The Sublime

The concept of the sublime, which refers to experiences that inspire awe and wonder, often bordering on terror, is a recurring theme in Keats’s poetry. In works like “Ode on a Grecian Urn” and “Hyperion,” Keats explores the awe-inspiring aspects of art and nature that evoke profound emotional responses. The sublime in Keats’s poetry is characterised by its ability to transcend ordinary experience and connect individuals with something greater than themselves. This theme aligns with Edmund Burke’s and Immanuel Kant’s philosophies, which define the sublime as a mix of beauty and fear, elevating the human spirit. Keats’s unique contribution lies in his application of the sublime to everyday moments and natural scenes, making it accessible and relatable. Unlike Shelley, whose depiction of the sublime often emphasised political and revolutionary ideals, Keats focused more on personal and sensory experiences, highlighting the intimate and immediate impact of the sublime.

The Power of Art and Poetry

The transformative power of art and poetry is a pervasive theme in Keats’s work, reflecting his belief in the enduring value of creative expression. In “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” the urn itself becomes a symbol of art’s ability to capture and preserve beauty across time. Keats’s poetry often portrays art as a means of achieving a kind of immortality, transcending the limitations of human life. This theme is also evident in “Endymion,” where the protagonist’s quest for ideal beauty is intertwined with the creation of poetry. Keats’s view of art as a vital, almost sacred force contrasts with the utilitarian perspective of art prevalent in some of his contemporaries. While poets like Blake saw art as a vehicle for social and moral messages, Keats emphasised its intrinsic aesthetic value and emotional impact. His focus on the sensuous and immersive qualities of poetry contributed to a deeper appreciation of art as a source of solace and enlightenment, enriching the Romantic canon with his distinctive voice.

4) His Legacy

John Keats’s legacy is one of profound and enduring influence, transcending the brevity of his life and the initial critical indifference to his work. Despite his short life, dying at the age of 25, Keats’s poetry has left an indelible mark on the literary world, continuing to inspire and resonate with readers, poets, and scholars alike.

Keats’s posthumous reputation contrasts sharply with the mixed reception his work received during his lifetime. Initially, his poetry was met with harsh criticism from conservative publications such as the Quarterly Review and Blackwood’s Magazine. These critics dismissed Keats’s work as overly sentimental and lacking in discipline, a perspective that was heavily influenced by the poet’s affiliation with the so-called “Cockney School” of poetry led by Leigh Hunt. However, after Keats’s death, a reassessment of his work began, leading to a growing appreciation for his unique contributions to English literature.

One of the most significant aspects of Keats’s legacy is his influence on subsequent generations of poets and writers. The Romantic movement, which Keats was a part of, fundamentally reshaped English literature, emphasising emotion, nature, and individualism. Keats’s rich imagery, sensuous detail, and exploration of beauty and mortality set a new standard for poetic expression. His odes, in particular, are considered some of the greatest achievements in English poetry, inspiring later poets such as Alfred Tennyson, Matthew Arnold, and Gerard Manley Hopkins. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with its focus on vivid imagery and medieval themes, also drew heavily from Keats’s work.

Keats’s legacy extends beyond his direct influence on poetry. His letters, rich with insights into his creative process and philosophical musings, have become almost as celebrated as his poems. These letters reveal a deeply reflective and articulate mind, grappling with the nature of creativity, beauty, and existence. They have been extensively studied and quoted, providing invaluable context for understanding Keats’s work and the Romantic era as a whole. Moreover, his concept of “Negative Capability”—the idea that a great thinker or artist must be comfortable with uncertainties and doubts—has had a lasting impact on literary theory and criticism.

The narrative of Keats’s life itself has contributed significantly to his legacy. The romanticised image of Keats as the archetypal struggling artist, whose genius was unrecognised during his lifetime and who succumbed to an early death, has captured the imagination of readers and biographers. This narrative has been perpetuated in various forms of popular culture, including films, novels, and plays, further cementing Keats’s place in the public consciousness. The poignant love story between Keats and Fanny Brawne, immortalised in their letters and the film Bright Star, adds a personal dimension to his legacy that continues to intrigue and move audiences.

Keats’s legacy is also preserved through the many institutions dedicated to his memory. The Keats-Shelley Memorial House in Rome, where Keats spent his final days, and Keats House in Hampstead, where he wrote many of his most famous poems, are both significant cultural landmarks. These sites attract thousands of visitors each year, offering insights into his life and work and ensuring that his legacy remains vibrant and accessible to the public.

Academically, Keats’s work continues to be a rich field of study. Scholars examine his themes, language, and form, contributing to a deeper understanding of his place within the Romantic movement and his broader impact on literature. Conferences, journals, and publications devoted to Keats ensure that his work remains at the forefront of literary scholarship.

5) Some Verses

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; – John Keats

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; – John Keats

Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. – John Keats

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun; – John Keats

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk, – John Keats