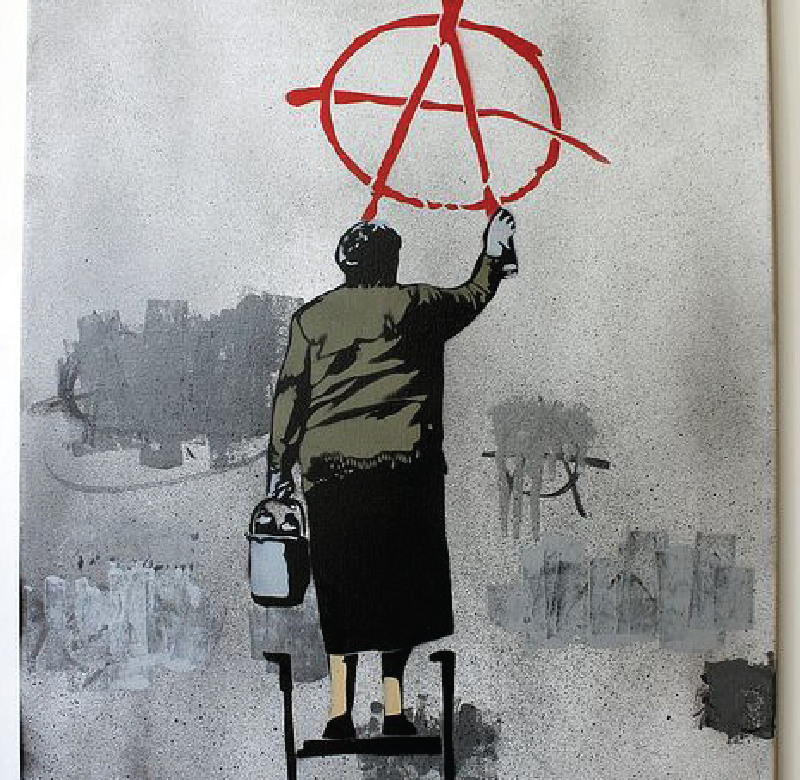

1) Proudhon, Father of Anarchism

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, often referred to as the “Father of Anarchism,” was a French philosopher and political theorist who played a pivotal role in shaping the anarchist movement. Born in 1809, Proudhon’s ideas were revolutionary for his time and continue to influence anarchist thought today.

Proudhon’s key contribution to anarchism was his critique of authority and the state. He famously proclaimed that “Property is theft!” This phrase encapsulates his belief that private ownership of property leads to exploitation and inequality. Proudhon argued for a society based on mutual cooperation, where individuals would have access to the fruits of their own labour without the need for oppressive hierarchies.

In his work, Proudhon envisioned a decentralised society organised through voluntary associations. He rejected the concentration of power in the hands of the state or any other authority, advocating instead for a system of direct democracy and self-governance. Proudhon’s ideas laid the groundwork for the concept of anarchy as a society free from coercive structures.

While Proudhon is often celebrated as a founding figure of anarchism, it’s important to note that his ideas were complex and evolved over time. He expressed contradictory views on certain matters, including the role of property and the use of violence. Nonetheless, his writings on mutualism, federalism, and worker self-management inspired generations of anarchists who sought to challenge oppressive systems and create a more egalitarian society.

Proudhon’s influence extended beyond anarchism. His ideas resonated with various socialist and labour movements of the 19th century. Many credit him with shaping the foundations of modern political and economic theory, including contributions to the fields of sociology and political philosophy. Proudhon’s ideas continue to spark intellectual debates and inspire activists who seek alternative ways of organising society based on principles of freedom and equality.

2) Forms of Anarchism

Anarchism encompasses a wide range of ideological currents and forms, each with its own distinctive characteristics and approaches to achieving a stateless society. While there is no single, monolithic form of anarchism, several prominent variants have emerged throughout history. These forms of anarchism share a common rejection of hierarchical authority and seek to promote individual freedom, cooperation, and non-coercive social relationships.

One significant form of anarchism is anarcho-communism. Rooted in the works of thinkers like Peter Kropotkin, anarcho-communism advocates for the abolition of both the state and private property. It envisions a society where resources are commonly owned and distributed according to individuals’ needs. Anarcho-communists argue that without the structures of capitalism and the state, people can freely cooperate and collectively manage their affairs.

Another notable form of anarchism is mutualism. Developed by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, mutualism seeks to establish a society based on voluntary economic exchanges between self-employed individuals and cooperative associations. Mutualists propose the replacement of traditional forms of private property with possession and use-based property norms. They emphasise the importance of reciprocity and equitable exchange within a market framework, while opposing exploitative practices.

Anarcho-syndicalism is yet another influential form of anarchism. Emerging from the labour movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, anarcho-syndicalism advocates for the revolutionary transformation of society through the direct action of workers organised in trade unions. Anarcho-syndicalists aim to create a society where workers collectively control the means of production and decision-making processes, challenging both capitalist exploitation and centralised state power.

Individualist anarchism, represented by thinkers like Max Stirner and Benjamin Tucker, places a strong emphasis on individual autonomy and self-determination. It rejects external authority and advocates for a society where individuals freely associate and pursue their own interests without interference. Individualist anarchists often emphasise the importance of property rights, self-ownership, and non-aggression.

Green anarchism, or eco-anarchism, combines anarchist principles with a strong focus on environmental sustainability and social ecology. It highlights the interconnections between ecological and social issues, criticising the destructive nature of capitalism and industrial civilization. Green anarchists promote decentralised decision-making, community self-sufficiency, and a return to sustainable and harmonious relationships with nature.

These are just a few examples of the diverse forms of anarchism that have emerged throughout history. Each variant brings its own unique perspective and strategies for achieving a stateless society. Despite their differences, all forms of anarchism share a commitment to dismantling oppressive systems, promoting individual freedom, and fostering non-hierarchical and voluntary forms of social organisation.

3) Anarchist Communism

Anarchist communism, also known as libertarian communism, is a form of anarchism that combines the principles of anarchism with the ideals of communism. It envisions a society without hierarchy, private property, or the state, where goods and resources are collectively owned and distributed according to the principle of “from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs.”

At its core, anarchist communism seeks to establish a society based on voluntary cooperation and mutual aid. It rejects both capitalist exploitation and the centralised control of resources by the state. Instead, it advocates for decentralised decision-making processes, where individuals and communities have direct control over their own lives and the means of production.

Anarchist communism emphasises the abolition of wage labour and the concept of economic class. It argues that in a truly free society, individuals should have equal access to the necessities of life and be able to pursue their passions and interests without the constraints of economic coercion. Work, in an anarchist communist society, is seen as a voluntary contribution to the collective well-being rather than a means of survival or accumulation of wealth.

To achieve this vision, anarchist communists propose a variety of strategies. These may include direct action, such as strikes, boycotts, and occupations, to challenge and undermine existing power structures. Anarchist communists also advocate for the creation of grassroots, horizontally organised institutions and communities that operate on the principles of mutual aid and voluntary cooperation. They envision a society where decision-making is carried out through consensus-based processes, ensuring that all individuals have an equal voice in shaping their own lives and communities.

Critics of anarchist communism argue that the elimination of private property and the state would lead to chaos or a lack of incentives for productive work. However, proponents argue that voluntary cooperation, solidarity, and the natural human desire for freedom and self-determination would be sufficient to create a functioning and sustainable society. They believe that in the absence of oppressive systems, people would be motivated by their own passions and the well-being of their communities.

4) Marxism and Anarchism

Marxism and anarchism are two distinct political ideologies that emerged in the 19th century and share some common critiques of capitalism and the state. While both ideologies aim for a society free from oppression and exploitation, they differ in their strategies, analysis of power, and approaches to achieving their goals.

Marxism, founded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, is a theory that emphasises the role of class struggle and the need for a transitional socialist state on the path to communism. Marxists argue that capitalism inherently produces social inequality and exploitation due to the private ownership of the means of production. They propose a centralised state apparatus to organise the revolutionary transformation of society, with the ultimate goal of establishing a classless, stateless communist society.

Anarchism, on the other hand, rejects the idea of a transitional state and advocates for the immediate abolition of all forms of hierarchical authority, including the state, capitalism, and other systems of domination. Anarchists argue that power structures, including the state, perpetuate inequality and restrict individual freedom. They promote direct action, voluntary cooperation, and grassroots organising as means to dismantle oppressive systems and create decentralised, self-managed communities.

One key difference between Marxism and anarchism lies in their views on the state. Marxists believe in utilising the state as a tool for achieving social change, viewing it as a temporary entity that can help facilitate the transition to communism. In contrast, anarchists see the state as inherently oppressive and argue for its abolition from the outset, as they view any concentration of power as a threat to individual freedom.

Another distinction lies in their approaches to economic organisation. While both Marxism and anarchism aim for a society free from capitalist exploitation, Marxists typically advocate for a planned economy, where production and distribution are organised by the state on behalf of the working class. Anarchists, on the other hand, advocate for various forms of decentralised, self-managed economies based on principles of mutual aid, voluntary cooperation, and direct democracy.

Despite their differences, there have been historical instances where Marxists and anarchists have collaborated in social movements and revolutions, particularly during periods of anti-capitalist and anti-authoritarian struggles. Both ideologies share a common critique of capitalism and the desire to create a more just and equitable society. However, tensions and disagreements over strategies, the role of the state, and the nature of power have also existed between Marxist and anarchist groups.

5) Anarchism and Capitalism

Anarchism and capitalism are two ideologies that are fundamentally at odds with each other due to their contrasting views on power, hierarchy, and economic organisation. Anarchism rejects the concentration of power and advocates for the abolition of all forms of hierarchical authority, including capitalism, while capitalism relies on hierarchical structures and the private ownership of the means of production.

Anarchism, as a political philosophy, opposes the existence of both the state and capitalism. Anarchists argue that capitalism perpetuates social inequalities and exploitation by concentrating wealth and power in the hands of a few. They view capitalism as inherently hierarchical, with capitalists and employers exerting control over workers and reaping the majority of the benefits from economic activity. Anarchists believe that capitalism fosters systemic oppression and restricts individual freedom by prioritising profit over the well-being of individuals and communities.

Anarchists advocate for economic systems based on voluntary cooperation, mutual aid, and decentralised decision-making. They propose various alternatives to capitalism, such as collectivism, mutualism, or communal ownership, where economic resources are owned and managed collectively by individuals or communities. Anarchist economic models prioritise equitable distribution, shared decision-making, and the well-being of all participants, aiming to eliminate exploitation and ensure that everyone has access to the necessities of life.

In contrast, capitalism is an economic system that revolves around private ownership of the means of production and the pursuit of profit. Capitalism relies on a hierarchical structure, where capitalists or business owners control the resources and decision-making, while workers are employed and compensated for their labour. It operates within a market framework, where goods and services are exchanged based on supply and demand.

Proponents of capitalism argue that it incentivizes innovation, productivity, and economic growth. They believe that the pursuit of individual self-interest, guided by market forces, leads to overall prosperity and the efficient allocation of resources. Capitalism is often associated with notions of individual freedom, private property rights, and the belief that voluntary transactions in the market should govern economic relationships.

However, anarchists critique capitalism for perpetuating social inequalities and concentrating power in the hands of a few. They argue that the pursuit of profit under capitalism can lead to exploitation, wage slavery, and the commodification of human relationships and natural resources. Anarchists also criticise the inherent hierarchies that arise within capitalist structures, where decisions are made by those with economic power, while workers have limited control over their own lives and workplaces.

6) Anarchism Today

Anarchism continues to be a relevant and vibrant political philosophy and movement in the present day, with various manifestations and influences across different social, environmental, and anti-authoritarian struggles. While anarchism has evolved and diversified over time, its core principles of rejecting hierarchical authority, advocating for individual freedom, and promoting voluntary cooperation remain central to contemporary anarchist thought and practice.

One area where anarchism has made significant contributions is in social and environmental justice movements. Anarchists often play active roles in grassroots organising, direct action campaigns, and protests against systemic oppression, such as racism, sexism, and class inequality. Anarchist ideas and tactics have influenced movements like Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and the global climate justice movement, with an emphasis on decentralisation, direct democracy, and challenging oppressive power structures.

Anarchism also continues to inspire alternative economic practices and models. Within the realm of labour organising, there is a growing interest in anarchist principles such as workplace self-management, cooperatives, and horizontal decision-making processes. Anarchist ideas have influenced movements advocating for the rights of gig workers, precarious labourers, and those seeking to create more democratic and equitable economic systems.

In recent years, anarchism has found resonance in struggles for community autonomy and self-governance. Anarchist principles of direct action, voluntary association, and mutual aid have informed movements fighting against gentrification, land enclosures, and the privatisation of public resources. Anarchists have actively participated in and supported autonomous social centres, squats, and community gardens, seeking to create spaces that challenge traditional power structures and foster solidarity and cooperation.

Technology and digital spaces have also become arenas where anarchist ideas find expression. Anarchist hackers and digital activists work towards an open and decentralised internet, advocating for privacy, anonymity, and free access to information. The principles of voluntary association and self-governance underpin projects like open-source software, peer-to-peer networks, and decentralised social media platforms, challenging the centralised control of online spaces.

While anarchism faces challenges and criticisms, including questions about its feasibility and effectiveness, it continues to inspire individuals and communities seeking alternatives to hierarchical and oppressive systems. Anarchist’s emphasis on self-determination, mutual aid, and direct action provides a framework for imagining and enacting a more egalitarian and free society. As social, economic, and ecological crises persist, anarchism remains a source of inspiration and a call to challenge power structures and strive for a world based on principles of freedom, equality, and solidarity.